Bloodhound car returns to the track for brake testing

- Published

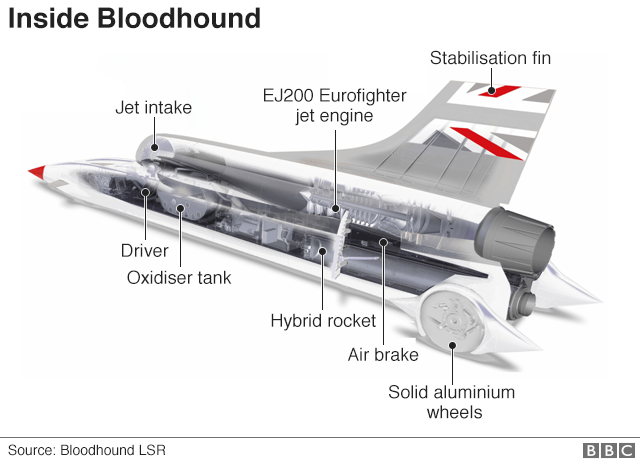

The airbrakes are panels that open into the air stream, producing drag to slow the car

The Bloodhound supersonic car returned to racing on Wednesday after four days of repairs in the workshop.

The vehicle swept down its desert track at 200mph (320km/h) - well short of its current best of 501mph (806km/h).

But Bloodhound's goal on this occasion was not to go superfast, but rather to gather data on its airbrakes.

These are "doors" that will project from the side of the car to produce the drag needed to slow the vehicle when travelling at the highest speeds.

They'll be an integral part of the running strategy during Bloodhound's attempts to break the existing land speed record of 763mph (1,228km/h) in 2020/21.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

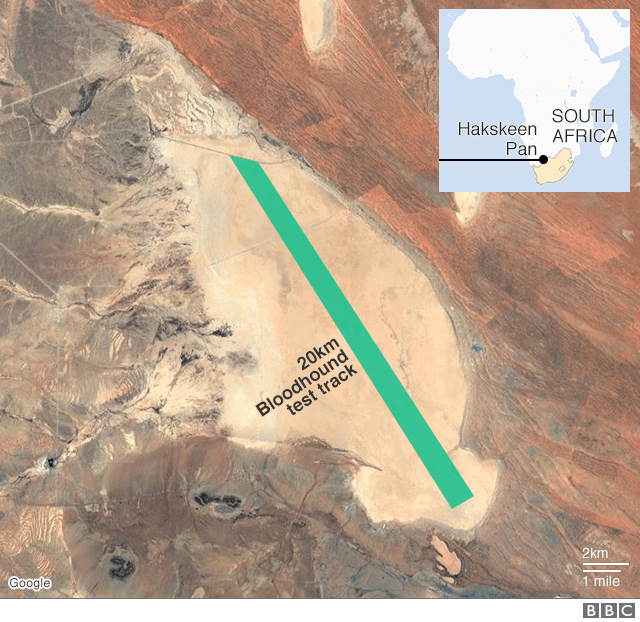

Even though the racetrack on Hakskeen Pan, South Africa, is over 10 miles (16km) long, the car is certain to use every inch when setting a new mark. It will need the room to get up to speed but then, crucially, also the room to stop in a controlled fashion.

Wednesday's outing was the first opportunity engineers have had to assess the airbrakes' influence on the car since beginning high-speed trials on the dried-out lakebed in Northern Cape.

The doors are not quite ready for operational use. That's because the full mechanism that would enable driver Andy Green to deploy them hydraulically from his cockpit has yet to be installed.

It means, therefore, the airbrakes must either be locked open or locked shut. And for the latest run, Bloodhound left the start line with the doors already ajar.

It will have given Wing Commander Green some initial understanding of how the airbrakes are likely to affect the handling of his car.

And for the aerodynamicists on the project - like Dr Ben Evans - the run will have provided data on how the doors change the air flows around the vehicle.

The Swansea University researcher is at Hakskeen Pan to watch the runs in person.

"Key for me in these high-speed trials are the 200 or so pressure sensors over the surface of the vehicle. They are what tell us whether the predictions we've made for the behaviour of the car in our computer modelling are correct," he told BBC News.

"In any computer model, there are some big assumptions - assumptions, for example, about the dust entrainment behind the vehicle, or exactly how the wheels interact with the ground.

"It's important therefore that we get a feel for whether those assumptions are sensible. So far in these trials, it's looking good."

Watch Bloodhound race past a camera buried in the track (Video by WorkerBee)

The car had to be stripped down over the weekend to fix various teething issues, including the replacement of a damaged sensor system that monitors overheating in the engine bay.

As luck would have it, Wednesday's run threw up another sensor issue, although the team was able to correct it after just a few hours' investigation.

The car will be back on the pan early on Thursday for a tilt at 550mph (885km/h).

The modelling suggests Bloodhound should be capable of posting a speed in excess of 600mph (965km/h) even though it's yet to be fitted with a rocket motor. Currently, its sole power unit is a Rolls-Royce jet engine from a Eurofighter.

With a rocket firing in tandem with the military turbofan, a speed above 800mph (1,285km/h) might be possible.

Bloodhound's probably got another couple of weeks of testing in Northern Cape before going home to England.

An attempt on the land speed record won't take place for perhaps 12 or 18 months. And for this to happen, sponsorship must be found to fund the car's return to Hakskeen Pan.

The supercar designed ultimately to go 1,000mph