Stars align for epic space missions

- Published

- comments

Artwork: Athena will be the most powerful X-ray space telescope ever built

Two of the most exciting space missions of the 2030s are likely now to be launched within a year of each other.

European Space Agency member states are poised to increase the organisation's science budget on Thursday by 10%.

This would make it possible to align projects to build a big X-ray telescope and a trio of satellites to sense the collision of gargantuan black holes.

It's important they fly together because the insights they'll bring are highly complementary.

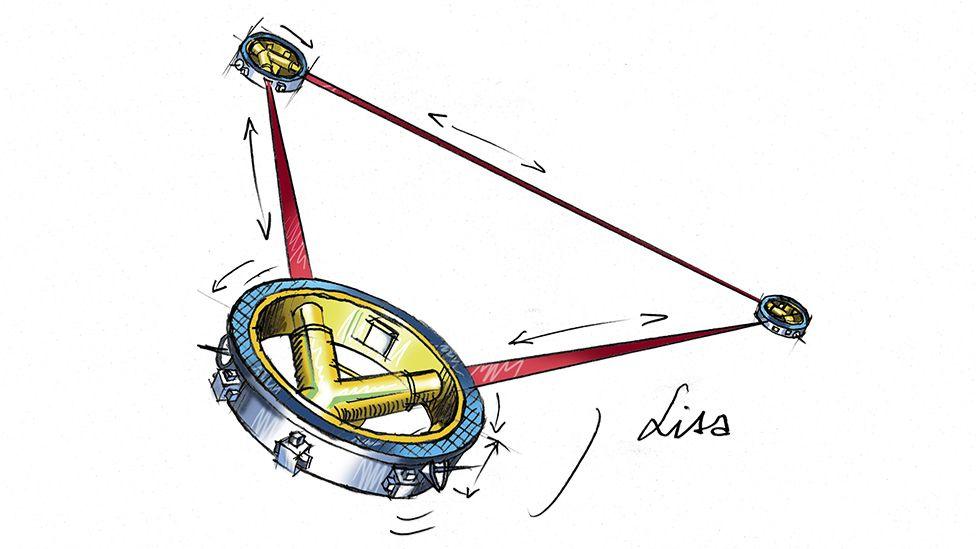

When black holes merge, they despatch vibrations across the fabric of space-time - so-called gravitational waves. And being violent events, these unions will potentially also emit high-energy radiation.

Scientists want the fullest picture possible and the Athena X-ray telescope, external and the Lisa observatory, external give them that opportunity.

"The idea is that there is light and sound together," said Prof Günther Hasinger, Esa's director of science.

"With gravitational waves, we hear the shaking Universe; and the light comes from the matter falling into the black holes - 'the last cry of help' that is radiating in X-rays," he told BBC News.

Prof Günther Hasinger: "This ministerial is really very important for science"

Both projects are big technology efforts that will take a decade to prepare. And their complexity is such that Esa would normally only try to launch missions of their kind once every five years.

But the budget increase set to be approved here in Seville, Spain, at the agency's triennial Ministerial Council, external, enables Athena and Lisa to be put on a similar development path.

It's hoped the X-ray telescope can launch in 2031 and the gravitational waves observatory in 2032.

The uplift in Esa's science funding to nearly €3bn (£2.6bn) over five years was one of the easiest discussions on the opening day of the Council. Research ministers didn't raise a word against the proposal, which means it should go through without issue when the meeting closes on Thursday.

Artwork: Lisa's three satellites will work together to detect gravitational waves

The Council is negotiating a wide-ranging package of space programmes valued at €12.5bn (£10.7bn) over three years, or €14.3bn (£12.3bn) when considered over five years.

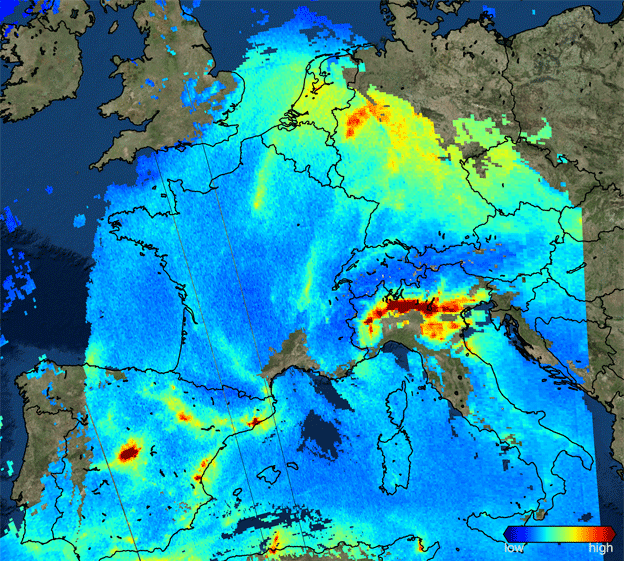

Another of the large ticket items is Earth observation, a key element of which is the recommended expansion of Copernicus, a suite of satellites called Sentinels that monitor the status of the planet.

Esa is already producing six sensor systems in this programme and it aims to start the planning for a further six after Seville. The agency asked for €1.4bn from ministers, and at the end of day one's deliberations had already collected bids for €1.7bn, the BBC understands.

The numbers could yet change when debate resumes on Thursday but already it's an impressive oversubscription, driven principally by France and Germany.

Nitrogen dioxide: Sentinel satellites gather information about the health of the planet

Of interest will be the number finally bid by the UK. That's because Copernicus is, in large part, an EU-backed project and Britain is supposed to be leaving the political bloc in January.

It will, though, be possible for the UK to re-join the Union's side of things as a "third country" at a later date. Brussels' Commissioner for space, Elżbieta Bieńkowska, said she hoped this would be the case.

"We, Europe, are the leaders in fighting climate change; and Copernicus will be the most important tool to do this. We need all of the European countries onboard, and that means we need the United Kingdom as a partner," she told reporters.

Certainly, any investments Britain makes in Copernicus with Esa will result in similar sized R&D contracts being given back to the nation's space companies.

Esa has put a multi-billion-euro package of proposals before member states

Commenting on a Ministerial Council after its first day always carries a "health warning". The size of bids being quoted can - and often do - change overnight. There is usually quite a bit of brinkmanship involved as different countries seek support for their pet projects.

In the arena of space safety, for example, Esa has proposed a mission called Hera, external which would visit an asteroid to learn more about the space rocks that threaten the Earth. In the same portfolio is a concept called Lagrange, a satellite that would stare at the Sun to warn of dangerous outbursts.

Germany wants Hera; the UK wants Lagrange.

"It's mankind's job to protect Earth against the asteroids, and so our focus is Hera," said Thomas Jarzombek, Germany's coordinator of aerospace policy. "And we believe it's a really hard challenge to do two of these large programmes."

Germany and the UK will be working hard to win the backing of other member states on Thursday.