Climate change: Study underpins key idea in Antarctic ice loss

- Published

Prof Hilmar Gudmundsson: "Thinning shelves have a mechanical impact on the ice behind them"

It's long been suspected but scientists can now show conclusively that thinning in the ring of floating ice around Antarctica is driving mass loss from the interior of the continent.

A new study finds the diminishing thickness of ice shelves is matched almost exactly by an acceleration in the glaciers feeding in behind them.

What's more, the linkage is immediate.

It means we can't rely on a lag in the system to delay the rise in sea-levels as shelves melt in a warmer world.

The glaciers will speed up in tandem, dumping their mass in the ocean.

"The response is essentially instantaneous," said Prof Hilmar Gudmundsson from Northumbria University, UK.

"If you thin the ice shelves today, the increase in flow of the ice upstream will increase today - not tomorrow, not in 10 or 100 years from now; it will happen immediately," he told BBC News.

The edge of Antarctica is bounded by thick platforms of floating ice. These "shelves" have formed as the continent's many glaciers have drained off the land into the sea.

On entering the water, their buoyant ice fronts have lifted and joined together to form a single protrusion.

But these shelves are being besieged by the invasion of warm ocean water that's now eating their undersides. And satellite data over the past 25 years has shown many to be thinning as a consequence.

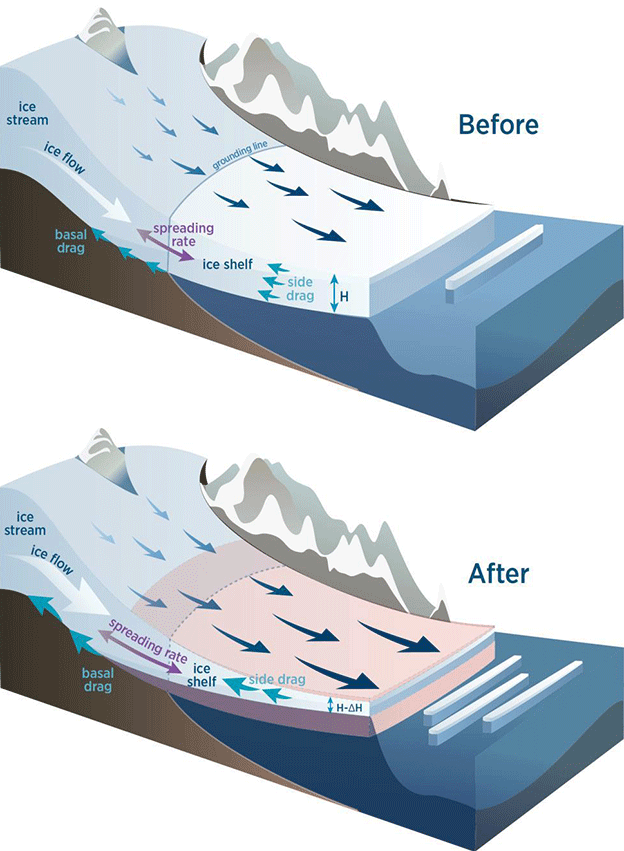

"That's a problem because the ice shelves act as a kind of architectural buttress, slowing the movement of the ice sheet behind them," explained Prof Helen Fricker, a satellite expert from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, US. "So, if you thin an ice shelf, the grounded ice behind can speed up, but what we didn't know was by how much - and that's where our work with Hilmar and his modelling comes in."

If you thin the floating shelf, the ice feeding in behind will accelerate

Prof Gudmundsson put Scripps' satellite data of shelf thinning into a numerical ice sheet model to see how the land ice should respond based on the current best understanding of the physics involved.

What the UK-US team found was that the predicted changes in the patterns of speed-up tallied precisely with what has been observed in the real world. What was previously just a correlation is now supported by quantifiable evidence.

"If the thinning of the ice shelves is driving the mass loss in the grounded ice, we would expect the pattern in the changes in velocities to match the observations - and that's exactly what we find," said Prof Gudmundsson.

The biggest changes are seen in the West of the continent, where huge glaciers such as Pine Island and Thwaites have accelerated in response to their denuded ice shelves. The ice volume contained in just these two ice streams would push up global sea levels by 1-2m - if it were all to melt out. The least change over the 25 years is seen in the East of the continent where shelves and their feeding glaciers have been largely stable.

Crevasses in a fast-moving glacier: The pattern of glacier speed-up matches the pattern of shelf thinning

Prof Andrew Shepherd is a Leeds University, UK, researcher affiliated to the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling. He was not involved in the new study, which is published in Geophysical Research Letters, external.

"It's fantastic to see how useful satellite data and models can be when used together," he told BBC News.

"Although most of the ice dynamical imbalance in West Antarctica and at the Antarctic Peninsula is clearly linked to ice shelf melting, there is not much evidence of the same in East Antarctica - which suggests Totten Glacier, for example, is thinning due to some other cause."

Totten is a behemoth the size of France. There was a suspicion some of the thinning witnessed at this glacier might simply be the result of reductions in snowfall, the Leeds scientist said.

Scripps' ice shelf data used in the Northumbria model was acquired over 25 years by a succession of European Space Agency (Esa) radar satellites.

Last week, Esa agreed to begin development of a new spacecraft in this series.

Codenamed the "Copernicus polaR Ice and Snow Topography ALtimeter" (CRISTAL) mission, external, it will eventually be incorporated into a constellation of EU-owned Earth observers known as the Sentinels.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external