Climate change: Satellite fix safeguards Antarctic data

- Published

Europe's quarter-century-long satellite data record of ice sheet changes in the Antarctic is secure into the future.

It's possible because a new spacecraft tasked with observing what's going on in the polar south is finally producing very serviceable data.

When the EU's Sentinel-3 mission was first launched in 2016, it struggled even to sense the continent's edge.

That problem's been fixed and its observations of the ice have now been shown to be consistent and accurate, external.

Antarctic Peninsula: Rugged terrain remains a challenge

Why is this important?

It comes down to how we know the Antarctic is melting.

Europe has flown an unbroken sequence of radar altimeters over the White Continent since 1991.

It is the data from these instruments, more than any other information source, that has established the melting trend in Antarctica.

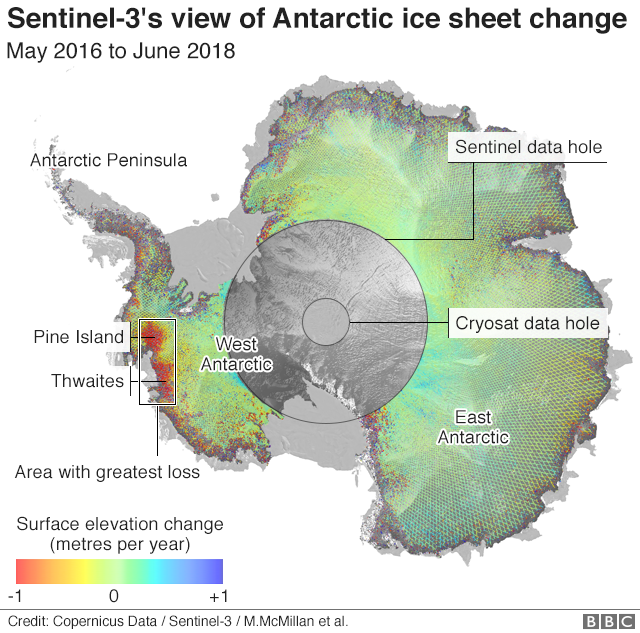

Mission after mission has detected a thinning of the ice sheet, in particular in its western sectors, with the loss of mass (some 200 billion tonnes per year) adding to global sea-level rise.

Currently, the primary altimeter is on a spacecraft called Cryosat, but this equipment is well past its design life and could fail at any time.

That's put pressure on scientists to prepare Europe's new Sentinel-3 platform, a workhorse satellite whose many roles includes measuring ice surfaces.

"For climate records you want to have these long-term, continuous time-series, and so we're very keen to be in the situation where, if Cryosat were to die, we could slot in Sentinel-3 and carry on," explained Dr Malcolm McMillan from Lancaster University's Centre for Environmental Data Science and the NERC Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM).

"I've been working with the Sentinel-3 data over the past year and I've been very encouraged. It's been convincing proof for me that the instrument is really good and will be very valuable."

Sentinel-3 is a multi-role satellite, with ocean monitoring being its major focus

What has been the concern with Sentinel-3?

Glaciologists were extremely troubled when they first saw what the Sentinel could do in the Antarctic. Or, rather, not do.

Radar altimeters work by pulsing the Earth's surface with microwaves, and then timing the reflected signal to work out an elevation. Repeat measurements reveal whether glaciers are thinning or thickening.

But the way the first Sentinel-3 mission operated its altimeter after launch meant it would lose the echoes as it crossed the continent's coastline. For a while, it was blind to the very parts of the frozen south where most of the changes are taking place.

This was soon corrected, but there were still doubts about the ice performance of the Sentinel's radar instrument.

Key areas of loss, such as Thwaites Glacier, are being detected by Sentinel-3

How have matters been improved?

Dr McMillan and colleagues have worked on new approaches to processing the sensor's data, comparing it with the observations made by a precise laser altimeter flown on an aeroplane.

The team has looked at regions in the flat interior of the continent - around Vostok and Dome C - and also at the margins - in Dronning Maud Land and Wilkes Land - where the topography can be very rugged. And the biases are now consistent and small, especially on the flatter terrain.

Sentinel-3's data still needs work where the terrain is steeply sloping - at the edges of Antarctica and along its peninsula - but in its first elevation map of the continent, the satellite is capturing the key areas of mass loss in the western ice sheet.

"Around Pine Island and Thwaites, it's clearly picking out the main signals of dynamic imbalance. These are the hotspots of thinning. So, it's seeing the important stuff," said Dr McMillan.

"The peninsula has always been difficult for radar altimeters, just because of the size of the radar footprint versus the size of the glaciers. But I think this is something that will evolve.

"It's easy to forget the Sentinel-3 mission is new and it's likely that as more people work on its data with new approaches - it will be possible to extract more information."

Artwork: Cryosat has a dual antenna interferometer that can better discern steep slopes

Is Sentinel-3 good enough... for ice?

Sentinel-3 can certainly do a job, and with funding already in place to fly four of these satellites Europe's radar observations of a changing Antarctic can continue unbroken into the 2030s. That'll represent an unambiguous climate trend of more than 40 years.

The question for the European Union and its technical partner, the European Space Agency, is whether they could do even better?

The Cryosat spacecraft - as its name suggests - is a specialised ice-monitoring satellite. It was an experiment with dual-antenna technology that outperforms all other radar altimeters in those hard-to-sense mountainous locations.

It also flies closer to the pole, allowing it to see more of the ice sheet.

And that's vital not just in Antarctica but also at the other end of the planet, where the Sentinel leaves a large "data hole" that cuts off the top of Greenland.

"Mass loss in the northern part of Greenland has set in during the past years and as the polar amplification is leading to higher temperature rise in the north, it is absolutely crucial for mass loss estimates in the next decades to have an instrument that is covering the north of Greenland," Prof Angelika Humbert from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany, told BBC News.

European research ministers at the end of the year will be presented with the option to pursue a Cryosat follow-on mission, which currently has the codename of Cristal.

"Ground processing can be upgraded after launch, but not the altimeter itself," commented Dr Amandine Guillot from the French space agency (Cnes)

"That's why, for example, the Sentinel-3 altimeter is not able to retrieve as much data as Cryosat over the coastal zone of Antarctica.

"That is why the Cristal mission, which has the primary objective of ice monitoring, has a real added-value with respect to the Sentinel-3 mission."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 March 2016