Antarctic instability 'is spreading'

- Published

Thwaites Glacier is out of balance, and its ice loss is accelerating

Almost a quarter of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet can now be considered unstable, according to a new assessment of 25 years of satellite data.

By unstable, scientists mean more ice is being lost from the region than is being replenished through snowfall.

Some of the biggest glaciers have thinned by over 120m in places.

Losses from the two largest ice streams - Pine Island and Thwaites - have risen fivefold over the period of the spacecraft observations.

And the changes have seen a marked acceleration in just the past decade.

The driver is thought to be warm ocean water which is attacking the edges of the continent where its drainage glaciers enter the sea.

The British-led study has been presented here in Milan at the Living Planet Symposium, external, Europe's largest Earth observation conference.

It has also been published concurrently in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Artwork: The Esa satellite record incorporates over 800 million measurements of ice height

The overview stitches together the data from four overlapping satellite missions of the European Space Agency (Esa) - ERS-1, ERS-2, Envisat and Cryosat.

These spacecraft were all launched with radar altimeters to measure the change in height across both the eastern and western sectors of the ice sheet.

Their unified record from 1992 to 2017 was then combined with weather models to tease apart the elevation trends due to short-term variations in snowfall from those longer-term shifts in ice mass resulting from melting and iceberg calving.

"Using this unique dataset, we've been able to identify the parts of Antarctica that are undergoing rapid, sustained thinning - regions that are changing faster than we would expect due to normal weather patterns," said Dr Malcolm McMillan from Lancaster University and the UK's Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling.

"We can now clearly see how these regions have expanded through time, spreading inland across some of the most vulnerable parts of West Antarctica, which is critical for understanding the ice sheet's contribution to global sea level rise," he told BBC News.

The latter years in the satellite record show an accelerating loss

If West and East Antarctica are considered as a whole, this contribution is 4.6mm over the study period. It would have been more than a millimetre higher still had the eastern sector of the ice sheet not gained mass slightly over the period.

Even so, the observed losses in the west mean that the continent's input to the ever rising surface of the world's oceans is now tracking towards the upper end of projections.

The computer models contained within the last major assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) foresaw, in the central range, 5cm of sea-level rise coming from Antarctica by 2100.

As things stand, it's likely to be another 10cm higher, says CPOM colleague and lead author on the paper, Prof Andrew Shepherd from Leeds University.

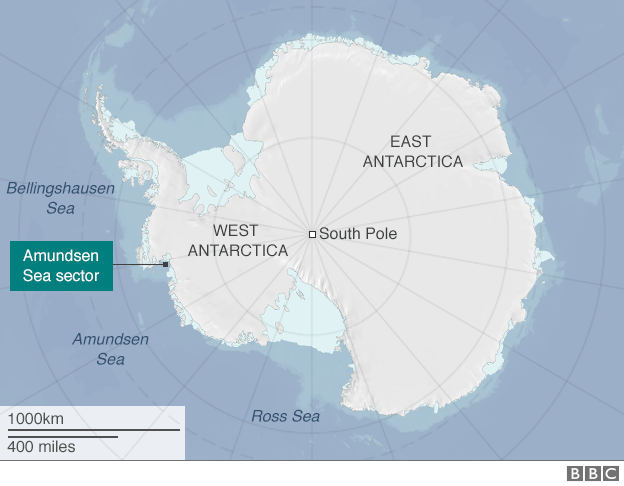

"There is a 3,000km section of coastline - including the Bellingshausen, Amundsen and Marie Byrd Land sections - that is clearly not properly modelled because that's where all the ice is coming from, and more ice than was expected," he explained.

"So, we need to go back to those models to try to understand what part of the signal they're not capturing. And, certainly, the altimeter data, which gives a very detailed description of the imbalance, should be the first thing people refer to."

There is now a concerted international effort to investigate the most rapidly changing areas.

This past expedition season saw a UK-US-led mission to gather geophysical information from the ocean in front of Thwaites Glacier. Repeat expeditions to the ice surface are planned for coming seasons.

Thwaites, and its neighbour Pine Island Glacier, appear to be the Achilles heel of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Sited in the Amundsen Sea sector, they account for by far the largest signal of imbalance. About 50% of their drainage basins are now losing mass, at average rates from 1992 of 28 billion tonnes a year at Pine Island and 46 billion tonnes a year at Thwaites.

But it is the acceleration that is telling, say the scientists.

Between 1992 and 1997, the loss rates were 2 billion tonnes per year and 12 billion tonnes per year, respectively. During the latter period of the survey (2012 to 2016), the rate rises to 55 billion tonnes and 76 billion tonnes per annum.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 June 2018

- Published9 April 2018

- Published5 April 2019