Satellite constellations: Astronomers warn of threat to view of Universe

- Published

Astronomers are concerned that the bright satellites could hinder their research

Astronomers are warning that their view of the Universe could be under threat.

From next week, a campaign to launch thousands of new satellites will begin in earnest, offering high-speed internet access from space.

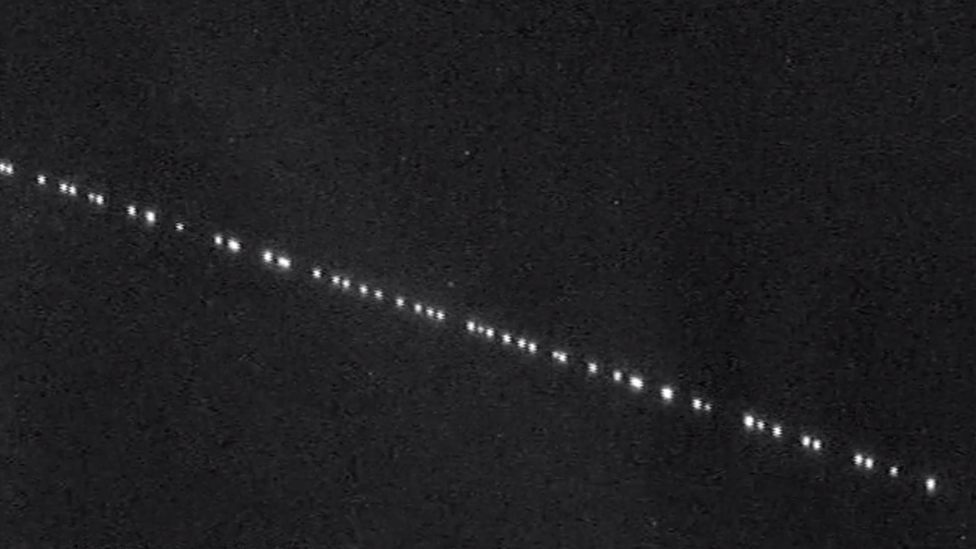

But the first fleets of these spacecraft, which have already been sent into orbit by US company SpaceX, are affecting images of the night sky.

They are appearing as bright white streaks, so dazzling that they are competing with the stars.

Scientists are worried that future "mega-constellations" of satellites could obscure images from optical telescopes and interfere with radio astronomy observations.

Dr Dave Clements, an astrophysicist from Imperial College London, told BBC News: "The night sky is a commons - and what we have here is a tragedy of the commons."

The companies involved said they were working with astronomers to minimise the impact of the satellites.

Why are so many satellites being launched?

It's all about high-speed internet access.

Instead of being constrained by wires and cables, satellites can beam internet access down to the ground from space.

And if you have lots of them in orbit, it means even the most remote regions can get connectivity.

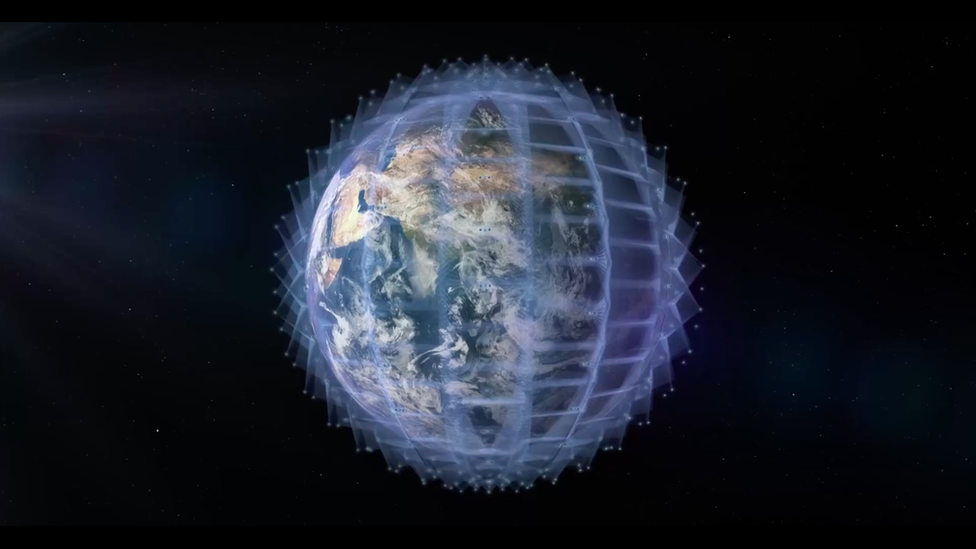

OneWeb's satellite constellation will sit 1,200km above the Earth

To give you an idea of the numbers, there are currently just 2,200 active satellites flying around the Earth.

But as of next week, the Starlink constellation - a project by US company SpaceX - will start sending batches of 60 satellites into orbit every few weeks. This will mean about 1,500 satellites have been launched by the end of next year, and by the mid-2020s there could be a fleet of 12,000.

UK company OneWeb are aiming for about 650 satellites - but this could rise to 2,000 if there is enough customer demand.

While Amazon have a constellation of 3,200 spacecraft planned.

Why are astronomers worried?

In May and November, Starlink sent 120 satellites into orbits below 500km.

But stargazers were concerned when the spacecraft appeared as bright white flashes on their images.

The Gemini Observatory recorded a trail of Starlink satellites

Dhara Patel, an astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich said: "These satellites are about the size of a table, but they're very reflective, and their panels reflect lots of the Sun's light, which means that we can see them in images that we take with telescopes.

"These satellites are also big radiowave users… and that means they can interfere with the signals that astronomers using. So it also affects radio astronomy as well."

She warns that problem will grow as the numbers of satellites in orbit increase.

What could this mean for research?

Dr Clements believes the satellites could have a real impact on observations.

"They present a foreground between what we're observing from the Earth and the rest of the Universe. So they get in the way of everything.

"And you'll miss whatever is behind them, whether that's a nearby potentially hazardous asteroid or the most distant Quasar in the Universe."

He said it would be particularly troublesome for telescopes taking large surveys of the sky, such as the future Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) in Chile.

He explained: "What we want to do with LSST and other telescopes is to make a real-time motion picture of how the sky is changing...

"Now we have these satellites that interrupt observations, and it's like someone's walking around firing a flashbulb every now and again."

But Prof Martin Barstow, an astrophysicist from the University of Leicester said some of the problems could be fixed.

"The numbers of satellites do sound frightening, but actually space is big - so when you superimpose them all on the sky, the density of these things is not going to be very large," he said.

"And because the satellites have known positions, you can mitigate. A satellite is going to be a dot in an image and it might appear as a transient burst of light - but you will know about it and can remove it from the image.

"It will cost effort and work for observatories to deal with it, but it can be done."

For radioastronomy, however, the constellations could pose more of an issue - especially for relatively new telescopes, such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA).

The radio signals the satellites use will be different from the ones astronomers are looking for, but they could still interfere, said Prof Barstow.

What do the companies involved say?

SpaceX want to see if they can make their satellites less bright

SpaceX told the BBC that they were actively working with international astronomers to minimise the impact of the Starlink satellites.

For their next launch, they are trialling a special coating that is designed to make the spacecraft less bright to see if this will help.

OneWeb said they wanted to be a "thought leader in responsible space" and were putting their satellites into an orbit of 1,200km so they would not interfere with astronomical observations.

Ruth Pritchard-Kelly, vice president of OneWeb, said: "We chose an orbit as part of our dedication to responsible use of outer space… And we've also talked to the astronomy community before we launched to make sure that that our satellites won't be too reflective, and that there won't be radio interference with their radio astronomy."

She added that it shouldn't be a case of having to choose between connectivity and astronomy.

"There is no question that the entire world is entitled to be connected to the internet…. So it's going to happen. And probably three or four of these systems are going to happen," she said.

"And the question will be working with the other stakeholders to make sure that we're not interfering with them, whether they are existing satellite technologies, or the mobile phone on the ground, or the astronomy community.

"We know we're going to work it out with everybody."

Stargazers will be watching the skies to see if a compromise can be found.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter., external

- Published24 May 2019

- Published27 February 2019

- Published22 February 2018