Plant life 'expanding over the Himalayas'

- Published

Shrubs and grasses in the Khumbu valley

Vegetation is expanding at high altitudes in the Himalayas, including in the Everest region, new research has shown.

The researchers found plant life in areas where vegetation was not previously known to grow.

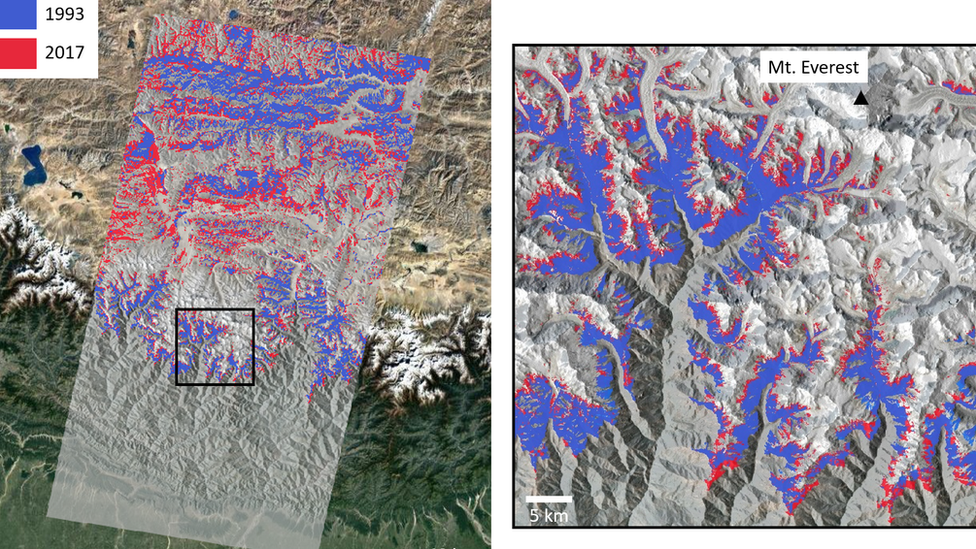

A team used satellite data from 1993 to 2018 to measure the extent of plant cover between the tree-line and the snow-line.

The results are published in the journal Global Change Biology., external

The study focused on the subnival region - the area between the tree-line (the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing) and the snow line (the boundary between snow-covered land and snow-free land).

Subnival plants are mainly small grasses and shrubs.

"The strongest trend in increased vegetation cover was between 5,000 metres and 5,500 metres altitude," said Dr Karen Anderson, from Exeter University, lead author of the report.

"At higher elevations, the expansion was strong on flatter areas while at lower levels that has been observed on steeper slopes."

Using Nasa's Landsat satellite images, the researchers divided the heights into four "brackets" between 4,150m and 6,000m.

It covered different locations in the Hindu Kush Himalayas, ranging from Myanmar in the east to Afghanistan in the west.

Earlier research had shown expansion of the tree-line at lower elevations

In the Everest region, the study found a significant increase in vegetation in all height brackets.

Other researchers and scientists working on glaciers and water systems in the Himalayas have confirmed the expansion of vegetation.

"It (the research) matches the expectations of what would happen in a warmer and wetter climate," said Prof Walter Immerzeel, with the faculty of geosciences at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study.

"This is a very sensitive altitudinal belt where the snowline is. A withdrawal of the snowline to higher altitudes in this zone provides opportunity for vegetation to grow."

The extent of vegetation in 1993 (blue) vs 2017 (red), derived from Landsat data in the region around Mount Everest

The research did not examine the causes of the change.

Other research has suggested Himalayan ecosystems are highly vulnerable to climate-induced vegetation shifts.

"We have found the tree-line expanding in the subalpine regions of Nepal and China as the temperature rises," said Achyut Tiwari, assistant professor with the department of botany at Nepal's Tribhuvan University.

"If that is happening with trees at lower elevations, clearly the plants at higher altitudes will also be reacting to the rise in temperature."

Some scientists regularly visiting the Himalayas have confirmed this picture of expanding vegetation.

"Plants are indeed colonising the areas that once were glaciated in some of these Himalayas," said Elizabeth Byers, a vegetation ecologist who has carried out field studies in the Nepalese Himalayas for nearly 40 years.

"At some locations where there were clean-ice glaciers many years ago, now there are debris-covered boulders, and on them you see mosses, lichens, and even flowers."

Some locations high up in the Himalayas have flowering plants like these

Little is known about plants at these even-higher altitudes, as most scientific studies have focused on retreating glaciers and expanding glacial lakes amid rising temperatures.

The researchers said detailed field studies on vegetation in the high Himalayas were required to understand how the plants interact with soils and snow.

"What does the change in vegetation mean for the hydrology (the properties of water) in the region is one of the key questions," said Dr Anderson.

"Will that slow down the melting of glaciers and ice sheets or will it accelerate the process?"

The Hindu Kush Himalayan region extends across all or part of eight countries, from Afghanistan in the west to Myanmar in the east. More than 1.4 billion people depend on water from this region.

Saussurea gossypifera at the Ngozumpa Glacier at 4,800m elevation