Barometric pressure in London 'highest in 300 years' at least

- Published

The weather forecasters have just given us an impressive display of their skill by predicting the scale of the current high pressure zone over the UK.

Overnight, Sunday into Monday, London's Heathrow Airport recorded a barometric pressure of 1,049.6 millibars (mbar).

It's very likely the highest pressure ever recorded in London, with records dating back to 1692.

But the UK Met Office and the European Centre for Medium Range Forecasts had seen it coming well ahead of time.

"Computerised forecast models run by the Met Office and the ECMWF predicted this development with near pinpoint precision, forecasting the eventual position and intensity of the high pressure area several days in advance, before it had even begun to form," said Stephen Burt, a visiting fellow at Reading University's department of meteorology.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

London didn't quite experience the highest of the high, however. That honour goes to the southwest of Britain.

Met Office hourly observation reports recorded 1050.3 mbar at Liscombe in Devon, at 2100 GMT on Sunday evening. 1,050.2 mbar was recorded at Dunkeswell in Devon, and 1,050.5 mbar at Mumbles, in South Wales, shortly after.

None of these measurements breach the 1,053.6 mbar recorded at Aberdeen Observatory at 2200 GMT on 31 January 1902, which remains the national record, but the events of the past 24 hours certainly marked the first time for over 60 years that 1,050 mbar has been attained anywhere in the British Isles, said Mr Burt.

"The reason for the extremely high pressure can be traced back to the rapid development of an intense low-pressure area off the eastern seaboard of the United States a few days previously (this is the storm that dumped around 75cm of snow in Newfoundland)," he explained.

"In simple terms, the air drawn out from this system through the actions of a strong jet stream has to be redistributed elsewhere.

"Normally, this would happen over a much larger area of the North Atlantic, leading to the rapid development of a fairly intense anticyclone, which is not uncommon. On this occasion, the 'excess air' (if we may call it that) could only be redistributed over a small area because of the existence of a number of other depressions, resulting in the rapid development and intensification of an anticyclone over the British Isles."

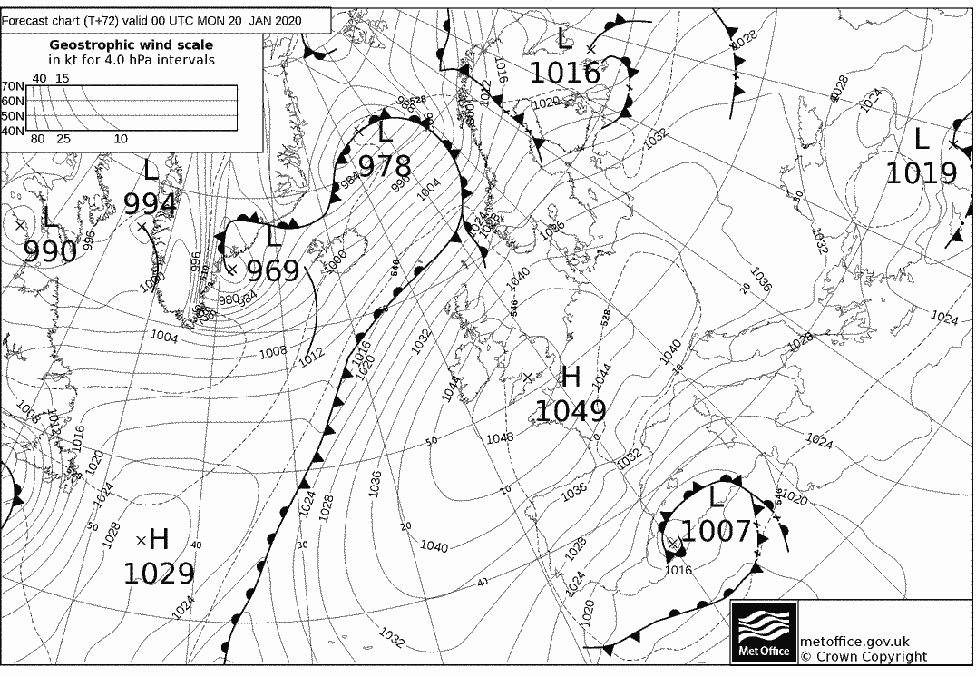

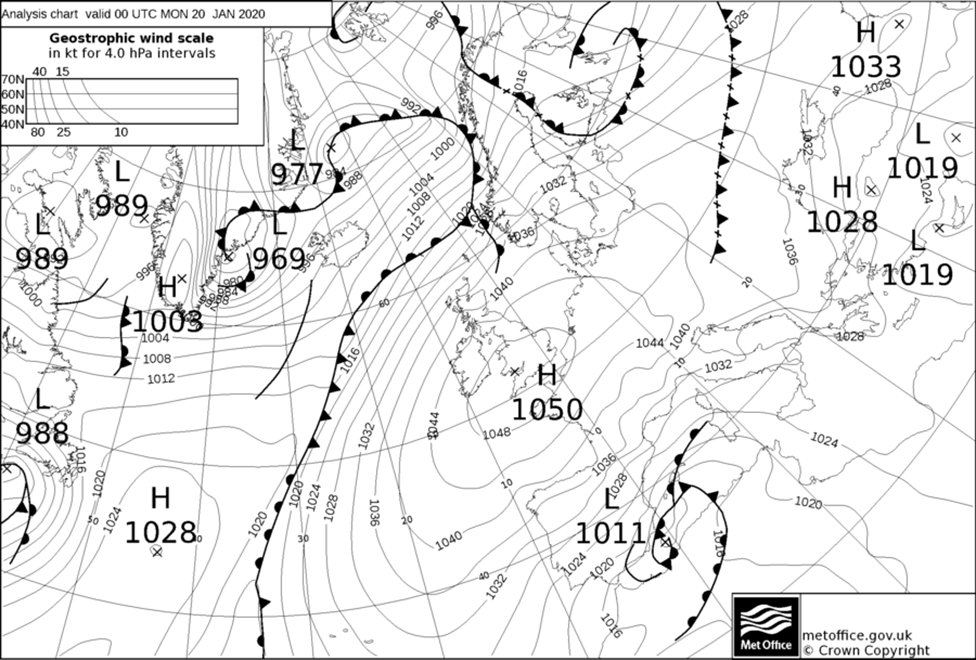

Compare the two charts below and try to spot the differences.

The first is a forecast made 72 hours (three days) ahead; the second one is the actual analysis for the same time, at midnight Sunday into Monday. This is the power of modern numerical models.

"It's remarkable that the models can accurately predict a 1-in-90 year event days ahead, not just 'day-to-day' weather," Mr Burt remarked. "At the time the 72-hour forecast was made, the high had not even begun to form!" he told BBC News.

The 72-hour look ahead

Analysis at midnight into Monday

Newfoundland in North America has been experiencing "snowmageddon"

Improvements in medium range weather forecasting took another important step forward this month with the introduction into ECMWF models of a novel set of global wind data.

The measurements - acquired by a laser operated from orbit by Europe's Aeolus satellite - allow meteorologists to maintain their forecast skill as they look a few more hours into the future for conditions that are likely to develop in several days' time.

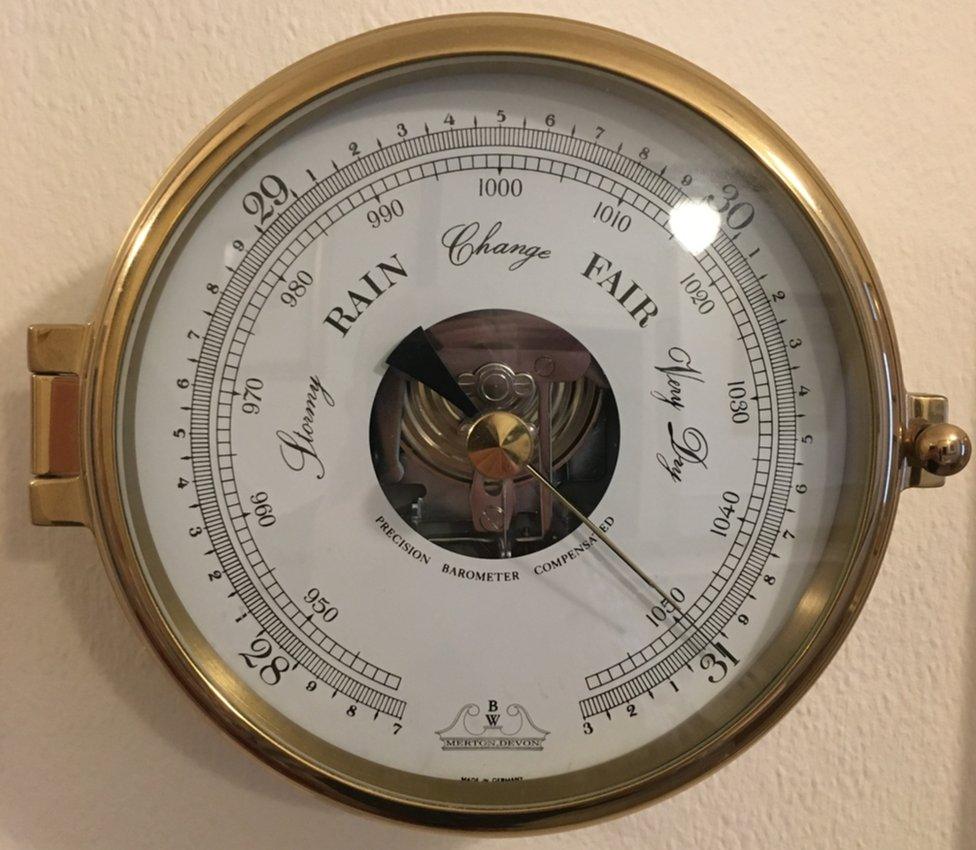

Barometers across the country recorded the exceptional conditions

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external