Neanderthal 'skeleton' is first found in a decade

- Published

The ribcage of Shanidar Z

Researchers have described the first "articulated" remains of a Neanderthal to be discovered in a decade.

An articulated skeleton is one where the bones are still arranged in their original positions.

The new specimen was uncovered at Shanidar Cave in Iraq and consists of the upper torso and crushed skull of a middle-aged to older adult.

Excavations at Shanidar in the 1950s and 60s unearthed partial remains of 10 Neanderthal men, women and children.

During these earlier excavations, archaeologists found that some of the burials were clustered together, with clumps of pollen surrounding one of the skeletons.

The researcher who led those original investigations, Ralph Solecki from Columbia University in New York, claimed it was evidence that Neanderthals had buried their dead with flowers.

This "flower burial" captured the imagination of the public and kicked off a decades-long controversy. The floral interpretation suggested our evolutionary relatives were capable of cultural sophistication, challenging the view - prevalent at the time - that Neanderthals were unintelligent and animalistic.

The skull of Shanidar Z was found to have been crushed

Before the most recent specimen uncovered in Iraq, the last articulated Neanderthal remains were unearthed at Sima de las Palomas in 2006-7, external and at Cova Forada in 2010, external [Link in Spanish]. Both sites are located in south-east Spain.

But Dr Emma Pomeroy, from the University of Cambridge, said the new skeleton - dubbed Shanidar Z - is more substantial and more completely articulated than those previous finds.

Dr Pomeroy is the lead author of a paper in Antiquity journal, external describing the find and was part of the excavation team working at the cave in Iraqi Kurdistan.

"So much research on how Neanderthals treated their dead has to involve returning to finds from 60 or even a hundred years ago, when archaeological techniques were more limited, and that only ever gets you so far," said Dr Pomeroy.

"To have primary evidence of such quality from this famous Neanderthal site will allow us to use modern technologies to explore everything from ancient DNA to long-held questions about Neanderthal ways of death, and whether they were similar to our own."

Ralph Solecki died last year aged 101, having never managed to conduct further excavations at his most famous site, despite several attempts.

The entrance to Shanidar Cave

In 2011, the Kurdish Regional Government approached Prof Graeme Barker from Cambridge's McDonald Institute of Archaeology about revisiting Shanidar Cave.

With Solecki's support, initial digging began in 2014, but had to be stopped after two days when Islamic State got too close. It resumed the following year.

"We thought with luck we'd be able to find the locations where they had found Neanderthals in the 1950s, to see if we could date the surrounding sediments," said Prof Barker. "We didn't expect to find any Neanderthal bones."

In 2016, in one of the deepest parts of the trench, the researchers identified a rib, followed by a lumbar vertebra - part of the spine. Then, they uncovered the bones of a clenched right hand. However, metres of sediment needed carefully digging out before the team could excavate the skeleton.

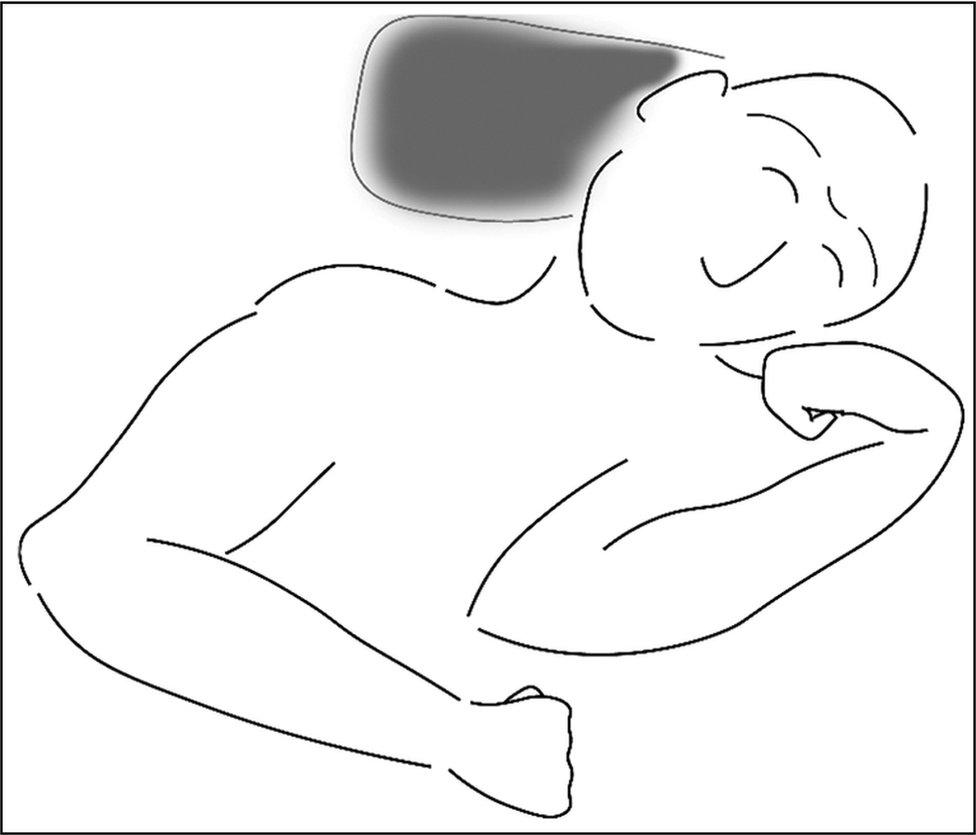

During the 2018-19 excavation, team members went on to uncover a complete skull, flattened by thousands of years of sediment, and upper body bones almost to the waist - with the left hand curled under the head like a small cushion.

Early analysis suggests the specimen is more than 70,000 years old. While the sex has yet to be determined, the discovery has relatively worn teeth, suggesting the individual was a "middle- to older-aged adult".

The bones of Shanidar Z's left hand

However, the lower part of the skeleton appears to be missing. "The ribcage and spine are almost complete, but [Shanidar Z] was cut off at about waist level by the removal of the block of sediment containing Shanidar 4 (another Neanderthal specimen from the site) in 1960," Dr Pomeroy told BBC News.

Shanidar Z's body lay right below Shanidar 4's upper body. "Observations by T Dale Stewart (the physical anthropologist on the 1960 project) and Ralph Solecki suggest there were a pair of legs just below Shanidar 4's head and upper body, and based on the limited information we have about the original position of the legs, they are very consistent with belonging to Shanidar Z," Dr Pomeroy explained.

It's possible that the lower legs and feet of Shanidar Z were misattributed to another of the Neanderthals from the cave, Shanidar 6. Unfortunately, many of the Shanidar remains are thought to have been lost during the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq.

A prominent rock next to the head of Shanidar Z may have been used as a marker for Neanderthals repeatedly depositing their dead, said Dr Pomeroy.

Diagram showing the burial position of the Neanderthal, a stone sits behind the head

But whether the time between deaths was weeks, decades or even centuries will be difficult to determine. Relationships between Shanidar Z and the other skeletons could potentially be resolved by analysing DNA.

But genetic material is difficult to obtain from hot regions of the world, and even if scientists can retrieve DNA from the new specimen, there may be little to compare it to, as many of the other remains are missing.

"The new excavation suggests that some of these bodies were laid in a channel in the cave floor created by water, which had then been intentionally dug to make it deeper," said Prof Graeme Barker. "There is strong early evidence that Shanidar Z was deliberately buried."

Shanidar Z has been brought on loan to the archaeological labs at Cambridge University, where it is being conserved and scanned to help build a digital reconstruction, as more layers of silt are removed.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external