Europe's small Vega rocket returns to action

- Published

The Vega left its Kourou launch pad at 22:51 local time, Wednesday (02:51 BST Thursday)

The European Vega rocket is back in business.

An enforced hiatus following the loss of a vehicle in July 2019 ended late on Wednesday with the successful deployment of 53 new satellites.

The payloads were dropped off high above the Earth using a new dispenser system that will now become a regular feature on future missions.

The aim is for Vega, external to service a big chunk of the vibrant market now emerging for small satellites.

Operators of these spacecraft, who're often just start-ups, SMEs or university departments, can't afford a dedicated launch and look to lower the cost by sharing a ride to orbit.

The new dispenser can deploy multiple satellites of various volumes and masses

The development of the Small Spacecraft Mission Service (SSMS) dispenser used on Wednesday's mission was largely funded by the European Space Agency.

"This launch demonstrates Esa's ability to use innovation to lower the costs, become more flexible, more agile and make steps towards commercialisation," the agency's director general, Jan Wörner, said.

"This enhanced ability to access space for innovative small satellites will deliver a range of positive results from new environmental research to demonstrating new technologies."

The dispenser can accommodate a range of volumes and masses - from the 1kg, 10cm-cubed nanosatellite (or cubesat) class, all the way up to the more bulky 500 kg minisatellites.

Indeed, one company aboard Wednesday's flight, Swarm Technology of San Francisco, deployed 12 tiny spacecraft that measured just 10cm by 10cm by 2.5cm. In other words, not a lot bigger than a smartphone.

These are to be used in a communications constellation relaying short messages and data from connected devices - what's known as a Machine-to-Machine service.

Artwork: GHGSat makes spot measurements of methane in the atmosphere

The heaviest satellite deployed, for an undisclosed customer, weighed 138kg.

The largest batch of payloads belonged to the Planet Earth observation company. It put up 26 of its "Super Doves". Planet will use the satellites to maintain its once daily image of the entire globe.

Super Doves, compared to previous iterations, have improved sensors that return enhanced spectral information, enabling more detailed analysis of objects and features on the ground.

One of the mid-sized satellites (15kg) onboard was a methane observer developed by GHGSat of Montreal.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and like carbon dioxide is increasing its concentration in the atmosphere.

The Canadian company aims to help reduce emissions by tracking down leaks from oil and gas facilities, amongst others, and alerting the owners to the problem.

GHGSat says it intends to set up its global analytics hub in the UK.

The Electron vehicle made its successful return to flight last week

Vega is the second rocket in a fortnight to make a return to flight following an earlier mishap.

The US-NZ Electron vehicle, operated by Rocket Lab, flew successfully from its base in New Zealand's North Island on 31 August.

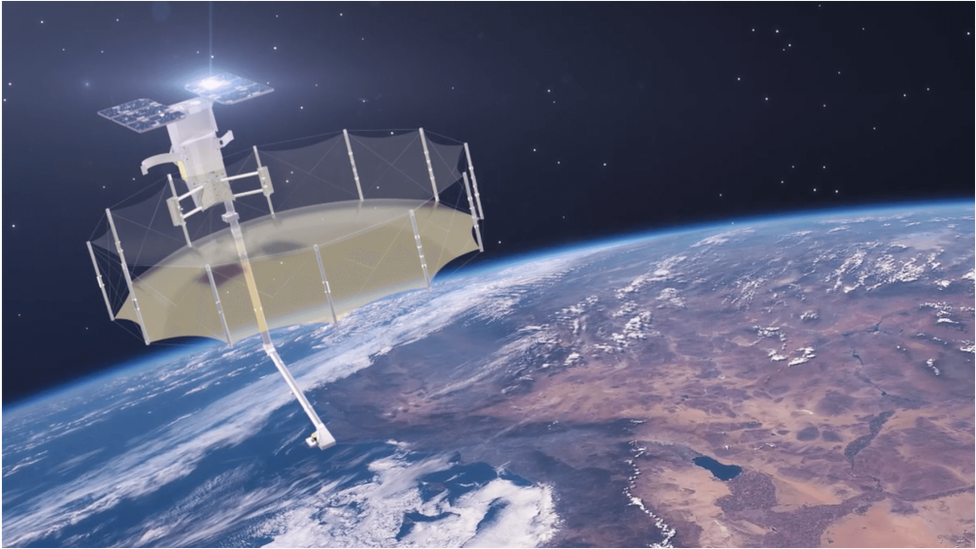

The rocket deployed just the one satellite - a novel radar platform for the American startup Capella Space.

Dubbed Sequoia, this sub-100kg spacecraft is designed to be the first in commercial network of similarly sized sensors.

Radar has the great advantage of always being able to see the surface of the planet, whatever the weather or light conditions.

The previous Electron's anomaly occurred during a flight on 4 July. The Vega failure occurred on 10 July last year. In both cases, engineers said they could identify the causes and were able to take corrective action.

Arianespace, which operates Vega from French Guiana, had tried to launch the vehicle at the end of June but was forced to let the flight slip because of a lengthy period of unacceptable wind conditions above the Kuorou spaceport.

Artwork: Sequoia is the first platform in a planned 36-strong satellite constellation

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external