Black hole breakthroughs win Nobel physics prize

- Published

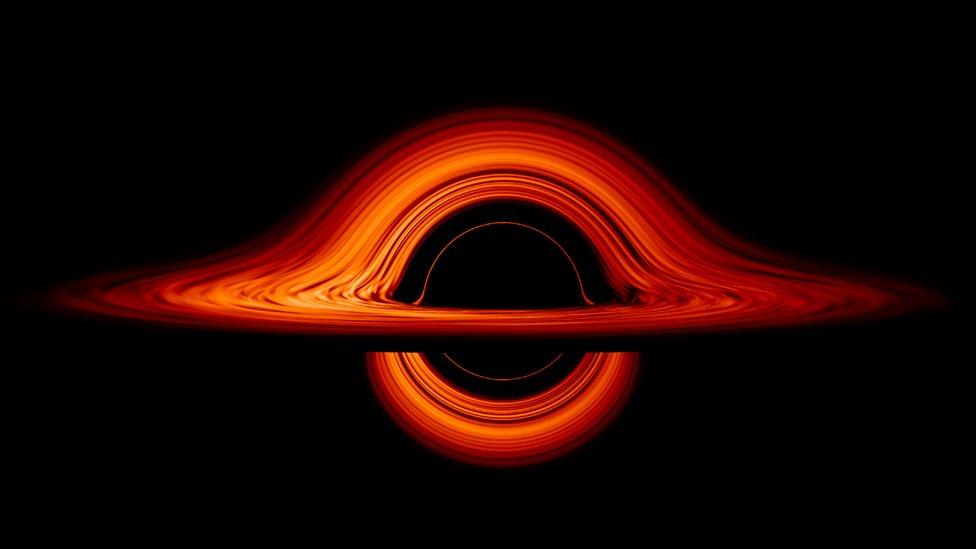

Recent visualisation of a black hole by Nasa

Three scientists have been awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for work to understand black holes.

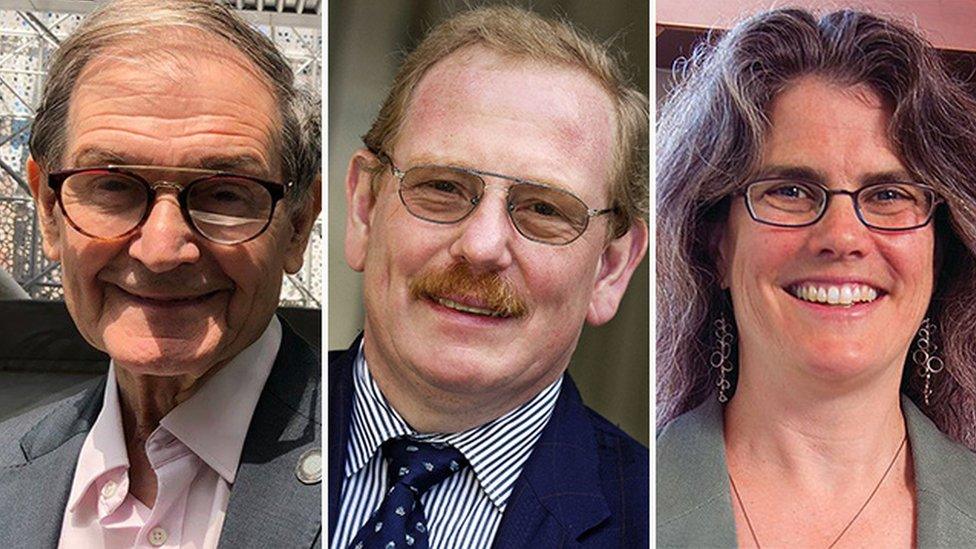

Sir Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez were announced as this year's winners at a news conference in Stockholm.

The winners will share the prize money of 10 million krona (£864,200).

David Haviland, chair of the physics prize committee, said this year's award "celebrates one of the most exotic objects in the Universe".

Black holes are regions of space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape from them.

UK-born mathematical physicist Sir Roger, from the University of Oxford, demonstrated that black holes were an inevitable consequence of Albert's Einstein's general theory of relativity.

Reacting to the win, he told the BBC: "It was an extreme honour and great pleasure to hear the news this morning, in a slightly unusual way - I had to get out of my shower to hear it."

Among scientific awards, he said, this is "the prime one".

L-R: Roger Penrose, Reinhard Genzel, Andrea Ghez

Penrose receives half of this year's prize, with the other half being shared by Genzel and Ghez. Prof Ghez is only the fourth woman to win the physics prize, out of more than 200 laureates since 1901.

The other female recipients are Marie Curie (1903), Maria Goeppert-Mayer (1963) and Donna Strickland (2018).

"The history of black holes goes way back in time to the end of the 18th Century. Then, through Einstein's general relativity, we had the tools to describe these objects for real," said Ulf Danielsson, a member of the Nobel Committee.

But the mathematics of black holes was incredibly complex. Many researchers believed they were nothing more than mathematical artefacts, existing only on paper. It took researchers decades to realise they could persist in the real world.

"That's what Roger Penrose did," said Danielsson. "He understood the mathematics, he introduced new tools and then could actually prove this is a process you can naturally expect to happen - that a star collapses and turns into a black hole."

Sir Roger explained: "People were very sceptical at the time, it took a long time before black holes were accepted... their importance is, I think, only partially appreciated."

Sir Roger showed that black holes always hide a singularity - a boundary where space and time ends

Penrose was born in 1931 in Colchester and comes from a distinguished scientific family. He is the son of the psychiatrist and geneticist Lionel Penrose and Margaret Leathes, who was the daughter of a well-known English physiologist. His brother Jonathan is a chess grandmaster.

Sir Roger shied away from competition as a child and struggled in exams. He told BBC Radio 4's The Life Scientific programme in 2016: "I was good at maths, but I didn't necessarily do very well in my tests." However, he added: "The teacher realised if he gave me enough time, I would do well.

"I think I had to do all my arithmetic working it out from first principles," he chuckled, adding: "I just was slow, and I'm slow at writing."

In the 1950s, he came up with the Penrose triangle, an impossible object which could be depicted in a perspective drawing but could not exist in reality. The triangle, along with other observations by Sir Roger and his father Lionel, influenced the Dutch artist MC Escher, who incorporated them into his artworks Waterfall, and Ascending and Descending.

Inspired by the British scientist Dennis Sciama, Penrose next applied his mathematical ability to physics. In 1965, he published a landmark paper in which he was able to show that a black hole always hides a singularity, a boundary where space and time ends.

What is a black hole?

A black hole, external is a region of space where matter has collapsed in on itself

The gravitational pull is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape

Black holes will emerge from the explosive demise of certain large stars

But some are truly gargantuan, billions of times the mass of our Sun

How these monsters - found at galaxy centres - formed is unknown

Black holes are detected from the way they influence their surroundings

The mathematical concept of "trapped surfaces," was crucial to this giant leap in understanding. A trapped surface forces all rays to point towards a centre, regardless of whether the surface curves outwards or inwards. Once matter begins to collapse, as in the formation of a black hole, and a trapped surface forms, nothing can stop the process from continuing.

Similarly, all matter crosses a black hole's event horizon in one direction, with everything carried towards an inescapable end at the singularity.

Sir Roger held a lectureship at Birkbeck College (now Birkbeck, University of London) at the time of the breakthrough, and it was on the way to his workplace that he had a moment of inspiration.

It occurred as he was in conversation with the physicist Ivor Robinson. The pair crossed a road and an image popped into Sir Roger's head of the trapped surfaces. He told the BBC: "Maybe it was having myself be a bit distracted from [the black hole problem] which led to me thinking about it in a different way."

Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez provided the most convincing evidence yet of a supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy - the Milky Way.

At the announcement of this year's recipients, Ulf Danielsson demonstrates the concept of a black hole using a ball

They found that this huge object, known as Sagittarius A*, was tugging on the jumble of stars orbiting it.

American Prof Ghez, from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), said: "I'm thrilled to receive the prize and I take very seriously the responsibility of being the fourth woman to win the Nobel prize [in physics]."

For more than 50 years, physicists had suspected that there may be a black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. But the technology had to catch up before this idea could be demonstrated.

In the 1990s, Prof Genzel, from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, and Ghez started using the world's largest telescopes to see through huge clouds of interstellar gas and dust to the centre of the Milky Way.

They stretched the limits of technology, having to develop new techniques to compensate for distortions to their observations caused by the Earth's atmosphere.

In 1988, Sir Roger was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize in physics along with Stephen Hawking for the Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems, an attempt to answer the question of when singularities are produced.

Swedish industrialist and chemist Alfred Nobel founded the prizes in his will, written in 1895 - a year before his death.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

Previous winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics

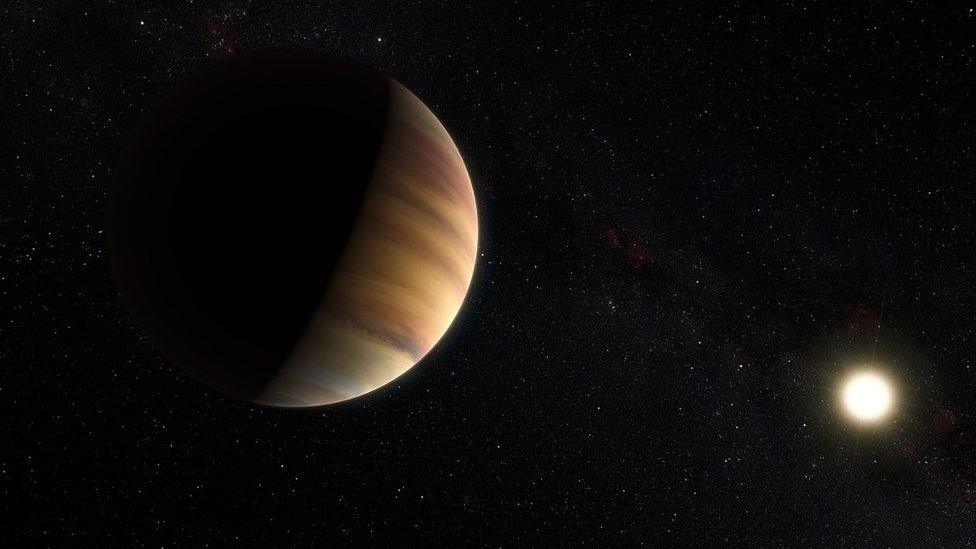

Artwork: Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz won in 2019 for their detection of the distant planet 51 Pegasi b

2019 - James Peebles, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz shared the prize for ground-breaking discoveries about the Universe.

2018 - Donna Strickland, Arthur Ashkin and Gerard Mourou were awarded the prize for their discoveries in the field of laser physics.

2017 - Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne and Barry Barish earned the award for the detection of gravitational waves.

2016 - David Thouless, Duncan Haldane and Michael Kosterlitz shared the award for their work on rare phases of matter.

2015 - Takaaki Kajita and Arthur McDonald were awarded the prize the discovery that neutrinos switch between different "flavours".

2014 - Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura won the physics Nobel for developing the first blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

2013 - Francois Englert and Peter Higgs shared the spoils for formulating the theory of the Higgs boson particle.

2012 - Serge Haroche and David J Wineland were awarded the prize for their work with light and matter.