James Webb Space Telescope's golden mirror in final test

- Published

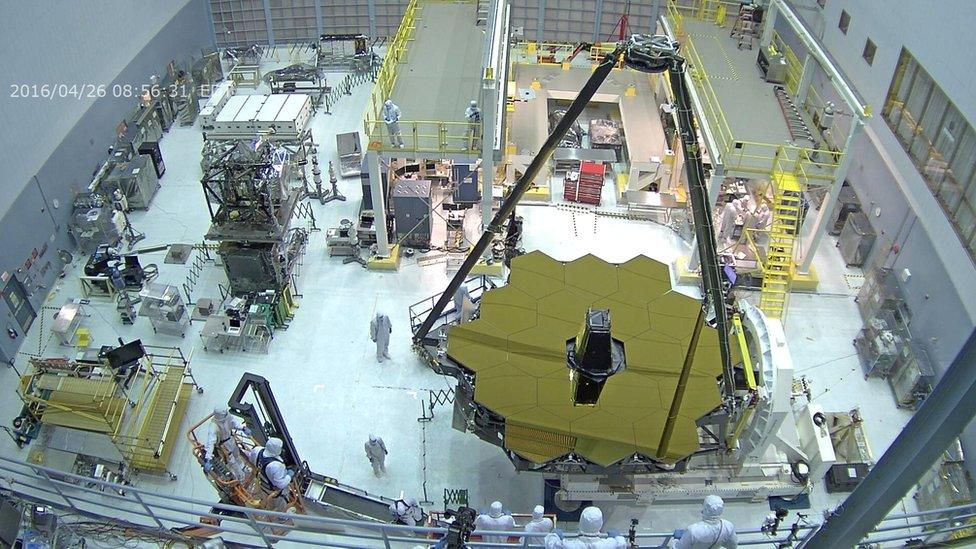

A timelapse showing engineers testing the unfolding of Webb's giant mirror

The technological marvel that is the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is going through final testing before being shipped to the launch site.

The successor to the mighty Hubble is due to leave Earth in October to begin a new era of astronomical discovery.

One of Webb's key objectives will be to catch the glow from the first stars to shine in the Universe.

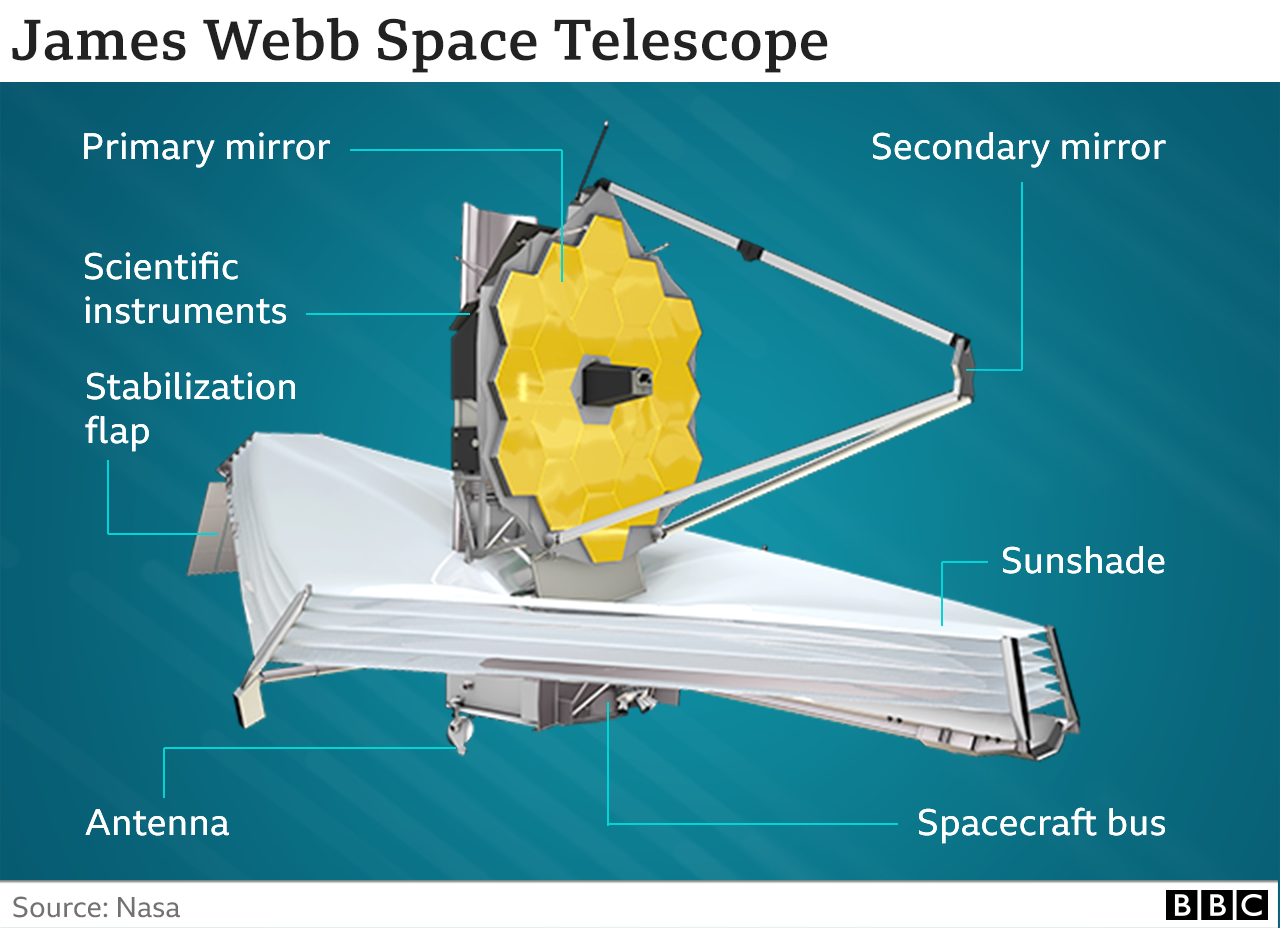

To do this, it's been given a 6.5m-wide, golden mirror that engineers are now checking one last time.

The segmented reflector has to be folded to fit inside the launch rocket - that's how big it is; and the technicians at aerospace manufacturer Northrop Grumman want to be sure that it'll have no problems being straightened out again once in space.

So, they've been simulating the deployment, first on one wing, and then, in the coming days, they'll do it on the other.

This involves supporting the mirrored panels from a crane in a way that mimics the zero-gravity environment off Earth.

"We effectively have that mirror float like it does in space," explained Northrop programme manager Scott Willoughby.

"We designed [the mirror wings] to operate in space, but we have to test them on the ground - and gravity can be pretty humbling."

The company has gone through the unfolding exercise for other stowable components, including the tennis-court-sized parasol that will shade Webb's observations from the Sun.

Soon, JWST - under the leadership of the US space agency (Nasa) - will be put inside a large container and taken on a ship from where it is now, in California, to the European rocket facility at Kourou in French Guiana - a two-week trip that will involve passage through the Panama Canal.

The European Space Agency (Esa), a key partner on the project, is providing the launch vehicle - an Ariane-5. Lift-off is scheduled for 31 October.

The days following will be exciting, and anxiety-laden. If Mars landers face "seven minutes of terror" when making the hazardous descent to the Red Planet's surface, then Webb will experience "two weeks of terror" as it unpacks all its systems on the way out to its observing position some 1.5 million km from Earth.

An early task will be to adjust the alignment of the mirror's 18 segments to produce useable images.

"When we take that first picture of a star about 40 days after launch, instead of a single star we're going to see 18 stars because each of the mirrors behaves as a single mirror," explained Begoña Vila, an instrument systems engineer with Nasa.

"The work we need to do is identify which star belongs to which mirror, and then bring them all together so at the end we have a single star that looks very nice, that is very well focused for all the instruments to use."

Astronomers from more than 40 countries worldwide have been allocated time on JWST in its first year of operation.

They will study all manner of targets, a number of them not even imagined when the telescope was originally conceived more than 30 years ago. Among them are the strange worlds we now know to exist in some planetary systems.

"There are observing programmes to look at exoplanets orbiting so close to a star that their surfaces are molten; they may have clouds of rock and even rain lava. Webb will be able tell if that is the case," said Klaus Pontoppidan, project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute which will manage the telescope during its lifetime.

James Webb will launch on Europe's Ariane-5 rocket

Unlike Hubble, Webb has not been designed to be serviced after launch. Astronauts will not visit it to repair and upgrade systems, as they did five times with the veteran space observatory.

That said, Webb has targets on it that would allow other spacecraft to approach it.

"If we get to the point where we're starting to run out of fuel, they might be able to mount a mission to go out and refuel JWST to keep it going," Nasa project manager Bill Ochs told reporters.

The $10bn James Webb Space Telescope is a joint venture between the US, European and Canadian space agencies.

It will be sensitive to infrared light. It's in this part of the electromagnetic spectrum that those distant, faint, early stars are expected to be apparent in very primitive galaxies.

The UK has made a major contribution to the telescope's Mid-Infrared Instrument (Miri) and provides a principal investigator to lead its observations.

- Published7 January 2021

- Published28 August 2019

- Published27 June 2018

- Published26 April 2016

- Published31 July 2015

- Published9 September 2013

- Published9 May 2012