Amazon-dwellers lived sustainably for 5,000 years

- Published

The researchers studied an area of forest in a remote corner of north-eastern Peru

A study that dug into the history of the Amazon Rainforest has found that indigenous people lived there for millennia with "causing no detectable species losses or disturbances".

Scientists working in Peru searched layers of soil for microscopic fossil evidence of human impact.

They found that forests were not "cleared, farmed, or otherwise significantly altered in prehistory".

The research is published in the journal PNAS, external.

Dolores Piperno is based at the Smithsonian's Natural History Museum in Washington DC and the Tropical Research Institute in Panama

Dr Dolores Piperno, from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, external in Balboa, Panama, who led the study, said the evidence could help shape modern conservation - revealing how people can live in the Amazon while preserving its incredibly rich biodiversity.

Dr Piperno's discoveries also inform an ongoing debate about how much the Amazon's vast, diverse landscape was shaped by indigenous people.

Some research has suggested the landscape was actively, intensively shaped by indigenous peoples before the arrival of Europeans in South America. Recent studies have even shown that the tree species that now dominates the forest was planted by prehistoric human inhabitants, external.

Dr Piperno told BBC News, the new findings provide evidence that the indigenous population's use of the rainforest "was sustainable, causing no detectable species losses or disturbances, over millennia".

To find that evidence, she and her colleagues carried out a kind of botanical archaeology - excavating and dating layers of soil to build a picture of the rainforest's history. They examined the soil at three sites in a remote part of north-eastern Peru.

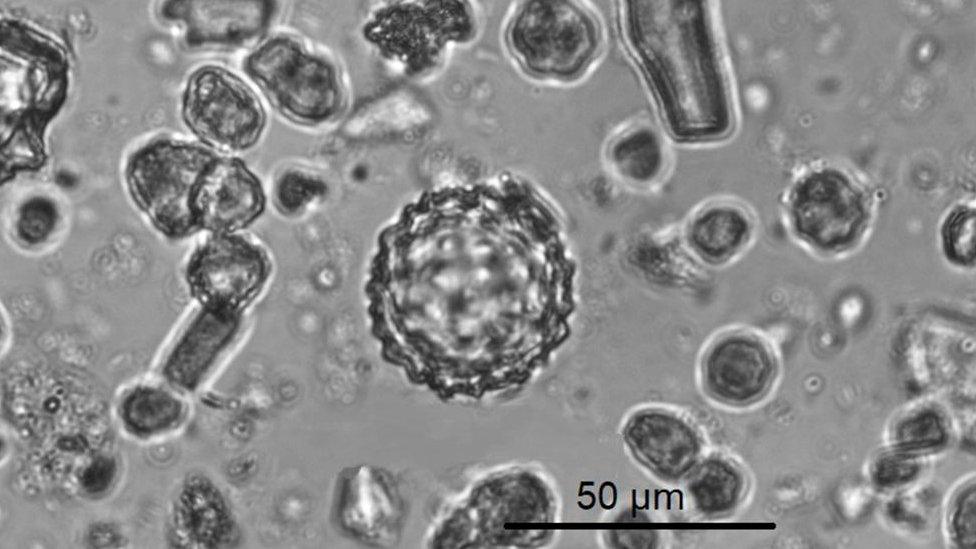

Phytoliths are microscopic plant fossils

All three were located at least one kilometre away from river courses and floodplains, known as "interfluvial zones". These forests make up more than 90% of the Amazon's land area, so studying them is key to understanding the indigenous influence on the landscape as a whole.

They searched each sediment layer for microscopic plant fossils called phytoliths - tiny records of what grew in the forest over thousands of years. "We found very little sign of human modification over 5,000 years," said Dr Piperno.

"So I think we have a good deal of evidence now, that those off-river forests were less occupied and less modified."

Dr Suzette Flantua from the University of Bergen is a researcher in the Humans on Planet Earth (Hope) project. She said this was an important study in working out the history of human influence on biodiversity in the Amazon.

"But it's like assembling a puzzle of ridiculous extent where studies like this are slowly building evidence that either supports or contradicts the theory that the Amazonia of today is a large secondary forest after thousands of years of human management," she said. "It will be fascinating to see which side ends up with most conclusive evidence."

The researchers sampled soil from the rainforest

The scientists say their findings also point to the value of indigenous knowledge in helping us to preserve the biodiversity in the Amazon, for example, by guiding the selection of the best species for replanting and restoration.

"Indigenous peoples have tremendous knowledge of their forest and their environment," said Dr Piperno, "and that needs to be included in our conservation plans".

Dr Flantua agreed, telling BBC News: "The more we wait, the more likely that such knowledge is lost. Now is the time to integrate knowledge and evidence, and establish a sustainable management plan for Amazonia and the prehistoric human presence should be included."

Follow Victoria on Twitter, external

You may also be interested in:

Brazil's environmental police in battle to reduce deforestation in the Amazon