Clouds of Venus 'simply too dry' to support life

- Published

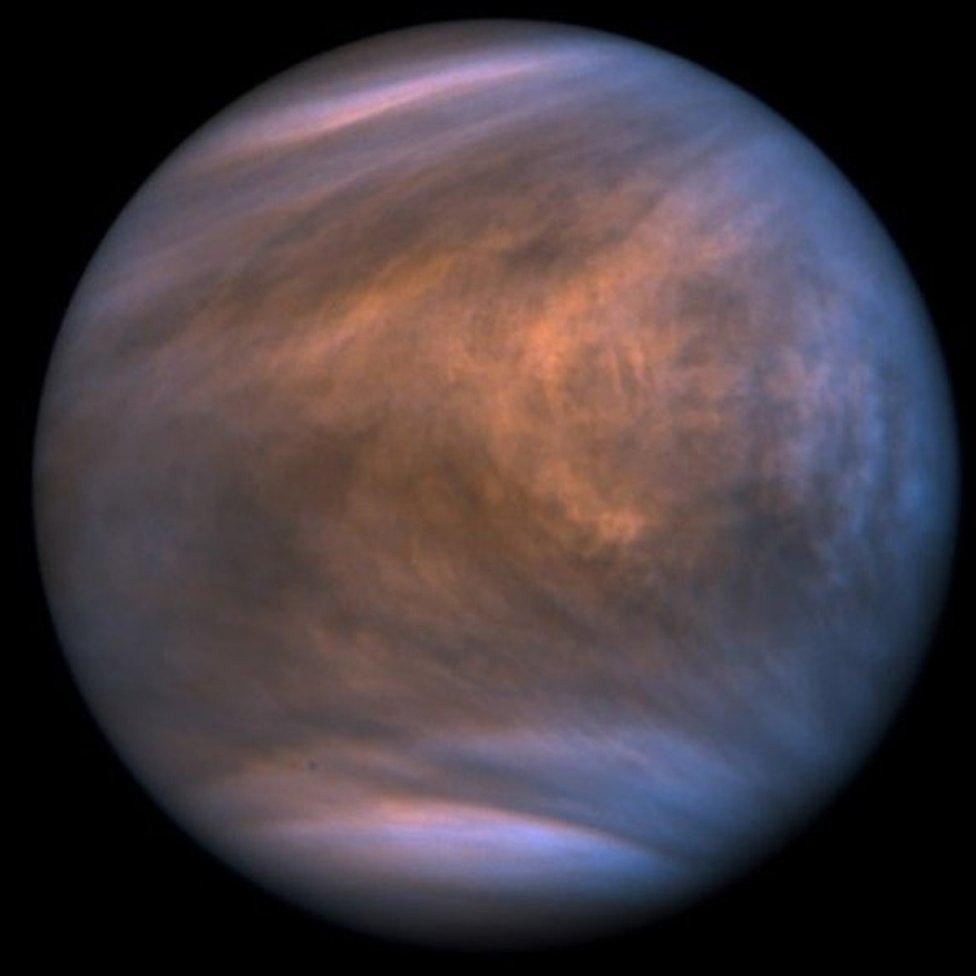

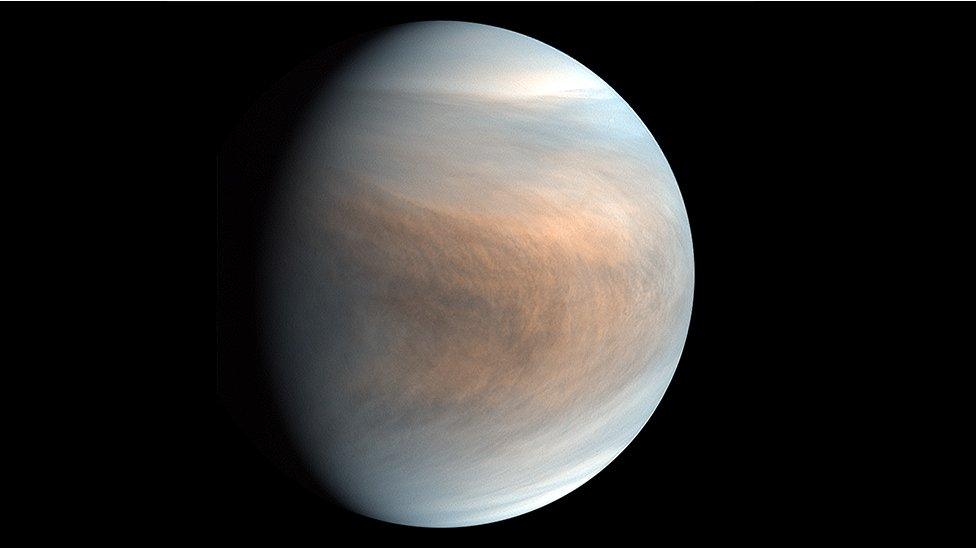

A view of Venus from the Japanese Akatsuki mission, which is currently in orbit around the planet

It's not possible for life to exist in the clouds of Venus.

It's simply too dry, external, says an international research team led from Queen's University Belfast, UK.

Hopes had been raised last year that microbes might inhabit the Venusian atmosphere, given the presence there of the gas phosphine (PH3).

It was suggested the concentration could not be explained by geological activity alone. But the new Belfast study puts a dampener on this idea.

The team assessed what is known about conditions in the clouds, gathered by space probes, and then looked across the library of lifeforms on Earth to see if any known organisms could persist in that challenging environment. The clouds are mostly sulphuric acid with a tiny fraction of water.

The analysis concluded that the most extreme "extremophile" - the name for microbes that live in very challenging conditions - wouldn't be able to survive, let alone thrive.

"We found not only is the effective concentration of water molecules slightly below what's needed for the most resilient microorganism on Earth, it's more than 100 times too low. It's almost at the bottom of the scale, and an unbridgeable distance from what life requires to be active," Dr John Hallsworth from Belfast's School of Biological Sciences said.

Does this "kill" the idea of detecting life on Venus?

It was certainly a thrilling and intriguing announcement when a separate team came forward last September with the tantalising observations of PH3 at the second planet from the Sun.

On Earth, phosphine is associated with life, with microbes living in the guts of animals like penguins, or in oxygen-poor environments such as swamps.

It's possible to make the gas industrially, but there are no factories on Venus; so its signal in the planet's clouds demanded an explanation.

September's team, led by Prof Jane Greaves from Cardiff University, raised the possibility of Venusian life, external and invited other groups to knock down the proposition.

Some astronomers initially questioned the correctness of the PH3 observations, which were made with two different telescope systems. But this latest challenge comes from a very different quarter - from experts in biochemistry. Dr Hallsworth is a microbiologist whose focus is the reaction of living organisms to stress.

Prof Greaves praised his work on Monday, describing the new study as an excellent piece of work. But she still thinks there is the possibility of a liveable window in the Venusian clouds.

"We spoke about this at some length last year; we know Venus's atmosphere is extremely desiccated but what we don't know is how well mixed it is.

"A colleague, Paul Rimmer, has a paper just out showing that some cloud droplets could have a very high water content," she told BBC News.

Prof Greaves highlighted the dark streaks sometimes seen on short timescales in the atmosphere in ultraviolet light. It's been speculated that these could be microbial colonies that evolve, die out and then re-emerge.

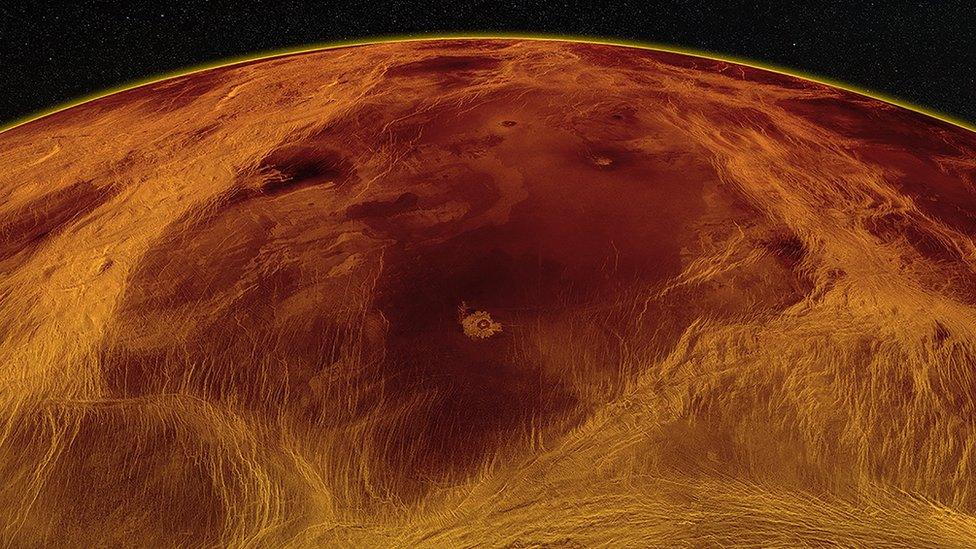

Artwork: The required water and temperature conditions exist in Jupiter's clouds

Dr Chris McKay is a leading figure in astrobiology, a field that examines the possibilities for life beyond Earth. The US space agency (Nasa) researcher, a co-author on the new Hallsworth study, said he would love to think Venus was inhabited but that the direct measurements of the atmosphere made by past probes really suggested this was unlikely.

More promising - although still very difficult to prove - is the notion that life might exist in the cloud layers of Jupiter.

The new research indicates compatible temperatures and water availability should be found at a depth where the pressure is about five times that at sea-level on Earth. Of course, this says nothing about the other requirements for life, such as a supply of nutrients.

"It's much harder to say a place is habitable than to say a place is not habitable, Dr McKay explained.

"To say a place is not habitable, all one has to do is show that some condition is beyond the range that life can tolerate. We've done that for Venus, unfortunately.

"We also show that one parameter - water activity - is within the range in a certain layer at Jupiter. But to show that this layer is habitable, we would have to go through all the requirements for life and show that they're all met. So it's much harder to say, Jupiter's atmosphere is habitable than it is to say Venus's clouds are uninhabitable."

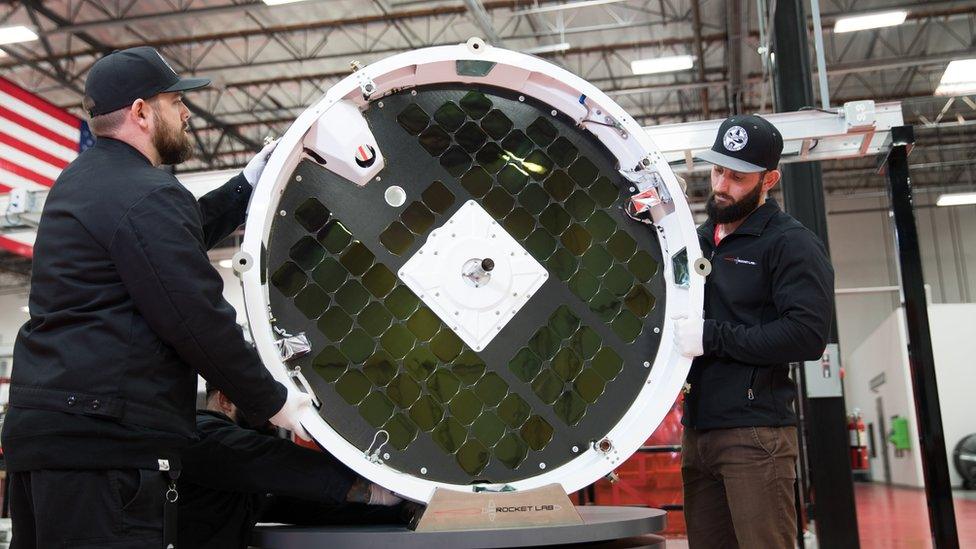

Rocket Lab's Photon mission: An entry probe will be dropped through the Venusian atmosphere

Venus is the hot planetary topic of the moment.

Nasa and the European Space Agency have just approved three new missions to go visit the world, starting at the end of this decade. And a private launch company, Rocket Lab, intends to send an atmospheric entry craft as soon as 2023. This has contributions from members of Prof Greaves' team and will look to sample the phosphine gas as the probe descends through the clouds.

Additionally, the team is about to formally publish responses to other scientists who doubted the robustness of their telescopic observations.

"We've looked at the data again, major improvements have been made [by the staff at the Alma observatory in Chile], and I'm really happy with what we've seen at Venus," Prof Greaves said.

The new Hallsworth study is published in the journal Nature Astronomy, external.

- Published22 June 2021

- Published10 June 2021

- Published3 June 2021

- Published14 September 2020

- Published14 September 2020

- Published22 March 2019