Climate change: US-Canada heatwave 'virtually impossible' without warming

- Published

- comments

The searing heat that scorched western Canada and the US at the end of June was "virtually impossible" without climate change, say scientists.

In their study, the team of researchers says that the deadly heatwave was a one-in-a-1,000-year event.

But we can expect extreme events such as this to become more common as the world heats up due to climate change.

If humans hadn't influenced the climate to the extent that they have, the event would have been 150 times less likely.

Scientists worry that global heating, largely as a result of burning fossil fuels, is now driving up temperatures faster than models predict.

Climate researchers have grown used to heatwaves breaking records all over the world in recent years. However, beating the previous national high temperature mark by more than 4C in one go, as happened in Canada last week, is virtually unprecedented.

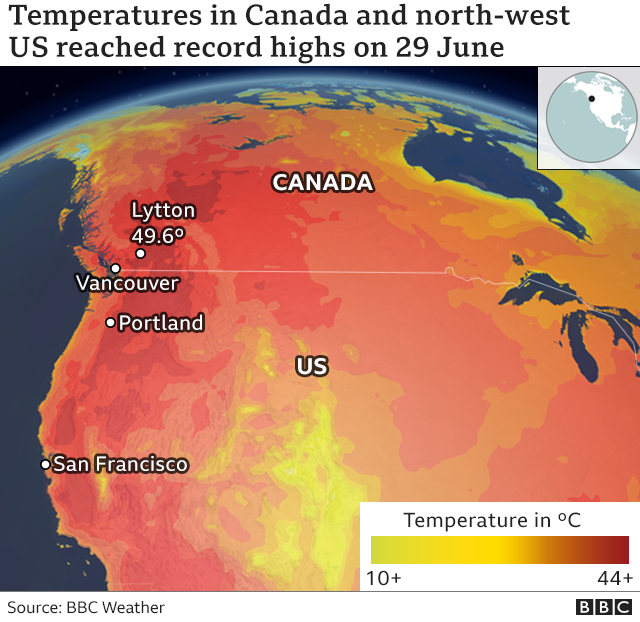

Canada's previous national record for high temperature was 45C - but the recent heat in the village of Lytton in British Columbia saw a figure of 49.6C recorded at the height of the event.

The remnants of the village of Lytton, in British Columbia, after a wildfire

This was shortly before the village itself was largely destroyed by a wildfire.

All across the region, in the US states of Oregon and Washington and in the west of Canada, multiple cities hit new records far above 40C.

These temperatures had deadly consequences for hundreds of people, with spikes in sudden deaths and big increases in hospital visits for heat-related illness.

Since the start of the heatwave, people have linked the unusual and extreme nature of the event to climate change.

Now, researchers say that the chances of it occurring without human-induced warming were virtually impossible.

An international team of 27 climate researchers who are part of the World Weather Attribution, external network managed to analyse the data in just eight days.

Unsurprisingly, given the quick turnaround, the research has not yet been peer-reviewed. However, the scientists use well-established methods accepted by top journals.

They used 21 climate models to estimate how much climate change influenced the heat experienced in the area around the cities of Seattle, Portland and Vancouver.

They compared the climate as it is today, with the world as it would be without human-induced warming.

"We conclude that a one-in-1000-year event would have been at least 150 times rarer in the past," said lead author Sjoukje Philip, from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

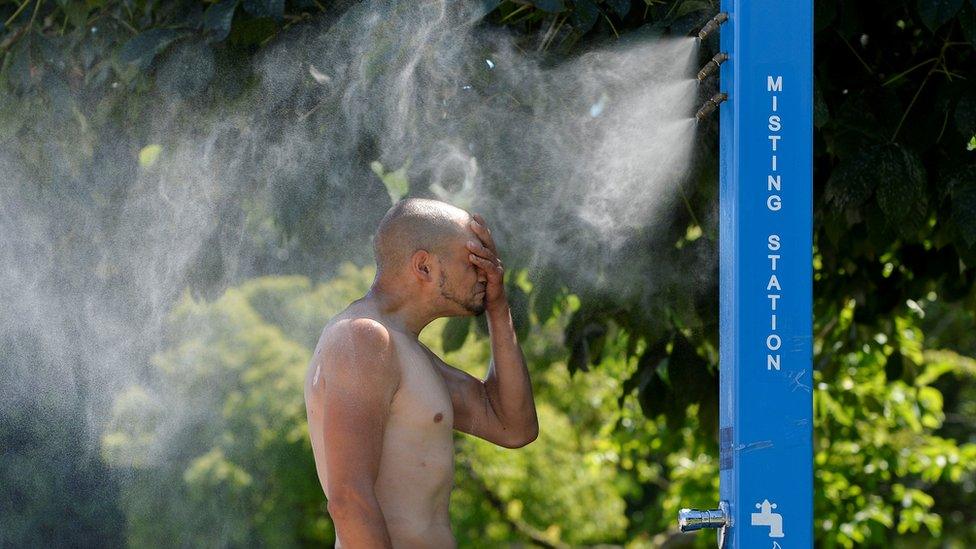

People suffered the impacts of heat across a large swathe of the western US and Canada

"So that's in a climate without human-induced climate change, when the climate was about 1.2C cooler than it is now. The heatwave would also have been about two degrees cooler in the past."

Co-author Dr Friederike Otto, from the University of Oxford, explained what the researchers meant when they said the extreme heat was "virtually impossible" without climate change.

"Without the additional greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, in the statistics that we have available with our models, and also the statistical models based on observations, such an event just does not occur," she explained.

"Or if an event like this occurs, it occurs once in a million times, which is the statistical equivalent of never," she told a news briefing.

This type of research, which seeks to determine the contribution of human-induced climate change to extreme weather events, is known as an attribution study.

According to the analysis, if the world warms by 2C, which could happen in about 20 years' time, then the chances of having a heatwave similar to last week's drop from around once every 1,000 years to roughly once every 5-10 years.

The authors say that the observed temperatures were so extreme that they lie far outside the range of historical observations. This makes it hard to quantify, with confidence, just how rare the heat dome event really was.

The scientists say there are two possibilities for the extreme jump in peak temperatures seen in the region.

The first is that it is just an extremely rare event, made worse by climate change, "the statistical equivalent of really bad luck", according to the paper.

People sought shelter from the heat in cooling centres set up across the region

The other possibility is that the climate may have crossed a "threshold," that would make the kind of heatwaves witnessed recently much more likely.

Up until now, researchers had seen a gradual increase in heat extremes as the world warmed. Their analysis of what happened in Canada has shaken that view.

It could mean that the predictions of climate models might be underestimating the extreme temperatures the world could yet experience.

"We are much less certain about how the climate affects heatwaves than we were two weeks ago," said Geert Jan van Oldenborgh, from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

"And we are worried about the possibilities of these things happening everywhere. But we don't know how realistic that is yet, we just we need to work on it."

So does mean that this exceptional heatwave could be some sort of tipping point?

"It's really not the important thing if this is a tipping point or not," said Dr Otto.

"What's important is what are our societies are resilient to and what can we adapt to. And in most societies, it's really a very, very stable climate, and that even a small change makes a huge difference."

"And what we see here is not a small change, it's a big change. I think that is really, really the important message here."

Follow Matt on Twitter., external

BBC Reality Check explains how to cut your carbon footprint