Why North America's killer heat scares me

- Published

We've just enjoyed our first blissful sleepover weekend with our 20-month granddaughter, Hazel, so maybe that softened me up.

Or perhaps it was a week's leave away from the news that rusted my BBC armour of emotional detachment from the climate story.

Either way, I confess to a gut-tightening sense of foreboding when Hazel left and I caught up with North America's killer heat dome on TV.

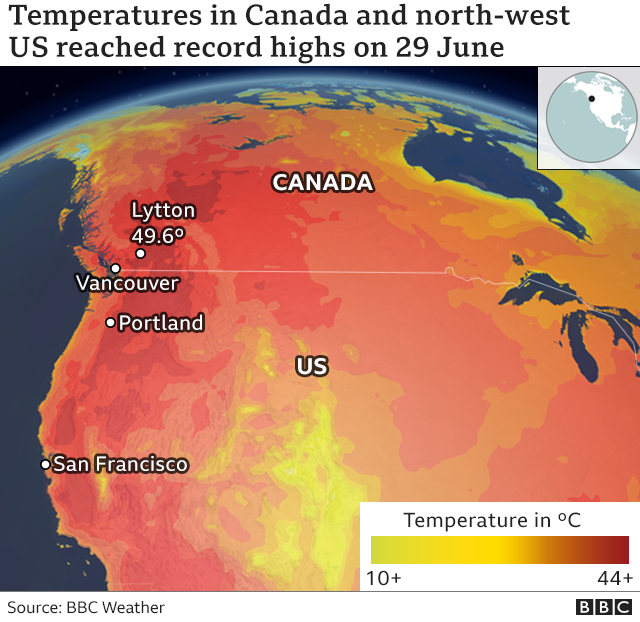

That's not because new record temperatures were set in the north-western US and Canada - that happens from time to time. No, it's because old records were smashed so dramatically.

The previous all-time Canada record of 45C was set in the 1937 Dust Bowl era when, like this year, the parched ground failed to mitigate temperatures.

Normally records like this are over-topped by a fraction of a degree, but this year the former high was obliterated on three days running.

The final temperature in the town of Lytton was fully 4.6C higher than the old record. Emissions from human activities inarguably contributed to the rise, increasing global average temperature by about 1.2C since the late 1800s.

A study by an international team of researchers this week concluded the heatwave that scorched western Canada and US was "virtually impossible" without climate change.

The team, which is part of the World Weather Attribution network, described it as a one-in-a-1,000-year event which would have been 150 times less likely without human influence on the climate.

Climatologists are nervous of being accused of alarmism - but many have been frankly alarmed for some time now.

"The extreme nature of the record, along with others, is a cause for real concern," says veteran scientist Professor Sir Brian Hoskins. "What the climate models project for the future is what we would get if we are lucky. The models' behaviour may be too conservative."

In other words, in some places it's likely to be even worse than predicted.

Computer models are what scientists use to try to second-guess the future behaviour of Earth's climate. But they take a very broad look across the global temperatures - they are not as accurate for smaller areas where the projected temperature extremes may be over-topped on a local level… extreme extremes, if you like.

Scientists are now striving to predict some of these crazy weather events that are currently taking policy-makers by surprise.

It's not just heat waves, but also pulses of torrential rain that cause devastating floods on a local level. Drains were built when no-one thought a harmless natural gas like CO2 could wreak havoc.

The UK Met Office hopes its shiny new megacomputer will be able to make projections on a much more closely defined scale, although some will be sceptical about its ability to do that.

Meanwhile, temperatures keep rising and shifting scientific goalposts. What's more, Canada's extreme extreme (sic) was cranked up by a global temperature rise of just 1.2C so far on pre-industrial levels.

But the world is probably heading for 1.5C of heating early next decade, and temperatures will push onwards to 2C and above unless policies radically change. What do we imagine things will be like with a rise of 2C, which was until recently considered to be a relatively "safe" level of change?

Baroness Worthington, a lead author on the UK's Climate Change Act, told me: "Concerned scientists are no longer concerned - they are freaked out.

"They're worrying there might not be a 'safe landing' on the climate. We are working on the idea of safe carbon budgets (the amount of carbon we can put into the atmosphere without badly disrupting the climate). But what if there is no safe carbon budget?

"What if the 'safe' carbon budget is zero. We can't sugar-coat the potential realities of this."

Politicians are working to avert the worst of those potential realities, but even the former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher remarked in the late 1980s that making such an experiment with our only planet was folly.

In 1989 she riveted the UN with her warning that greenhouse gases were "changing the environment of our planet in damaging and dangerous ways".

Mrs Thatcher - formerly a research chemist - continued: "The result is that change in future is likely to be more fundamental and more widespread than anything we have known hitherto. It is comparable in its implications to the discovery of how to split the atom. Indeed, its results could be even more far-reaching.

"It is no good squabbling over who is responsible or who should pay. We shall only succeed in dealing with the problems through a vast international, co-operative effort."

This was extraordinarily prescient, and her words were even more devastating from the lips of a towering, right-wing world leader who couldn't be dismissed as a fretful hippy.

If the world had heeded her warning back then, imagine where we would be now?

Watch: Lytton, British Columbia residents flee wildfires

But Thatcher's views were challenged by climate "sceptics" - some of them funded by a decades-long campaign of disinformation from fossil fuel firms.

Rich nations fixated on economic growth rather than saving the planet from a hypothetical threat, and developing economies asserted their "right" to pollute the air just as rich nations had done.

Wealthy countries stinted the cash they offered to poor nations to get clean technology. And international negotiations consistently failed to deliver the difficult and sweeping changes Mrs Thatcher thought necessary.

At last many leading nations are getting round to devising policies to reduce emissions over coming decades.

It's not just the heat dome they're worried about. We've learned recently about climate extremes in the Antarctic, the Himalayas and - dramatically shown on our interactive graphic - the Arctic.

Some scientists are warning that areas of the world will become uninhabitable if current trends continue. So what are our leaders doing to keep us safe?

Well, they're talking a good show, and doubtless some really mean to curb climate change. But the impacts of global heating are happening right now, whereas major nations plan to phase out emissions by 2050.

President Biden says CO2 will be halved against 2005 levels this decade. But his proposed investments in clean technology are being resisted by Republicans.

GM and others have promised to sell only vehicles that have zero tailpipe emissions by 2035. But the president has set no date for electrifying the US car fleet.

What's more his climate envoy John Kerry has attracted criticism for insisting that US lifestyles don't need to change, whereas experts say protecting the climate requires new technology as well as behavioural changes such as eating less meat and driving smaller cars.

And there's a gap in the policies of even a world-leading nation such as the UK, where the government plans a £27bn programme of road-building.

And, even though rail use has plunged since the pandemic, Boris Johnson is spending £100bn+ on the HS2 rail project that won't be carbon neutral until around the end of the century - no-one knows for sure.

The worlds of technology and business are showing some positive signs. The cost of solar and wind power, for instance, is plummeting. But these still only supply around 14% of the world's total energy demand, according to the renewables agency, IRENA.

Meanwhile a fractured gas pipe in the Gulf of Mexico has turned the ocean into flames and in London an investment trust for green industries failed to raise its minimum funding and was scrapped.

And in Asia 600 new coal fired power stations are planned, although admittedly, some are being withdrawn as investors realise at last that coal's a poor long-term bet.

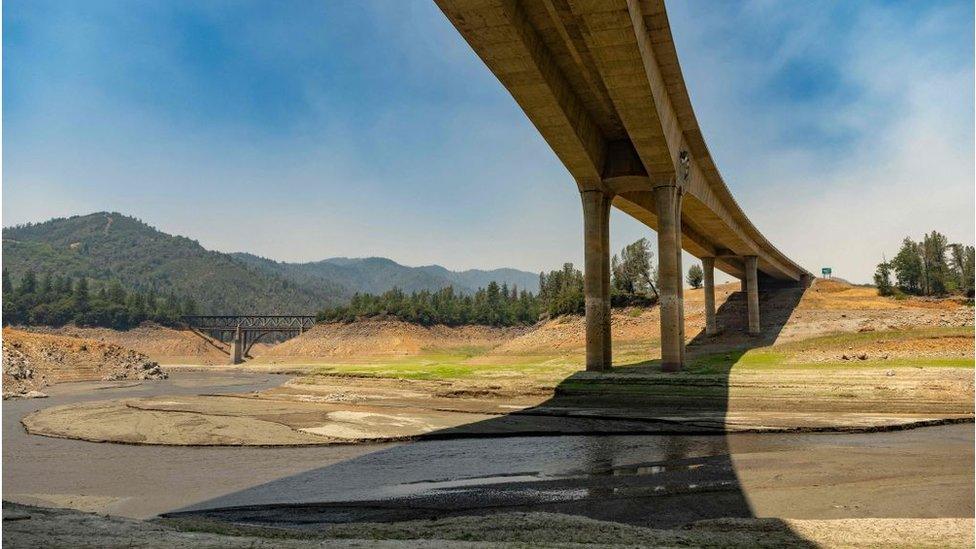

The drying bed of Lake Shasta in California

Against this backdrop the world's multi-billionaires are competing to use vast amounts of energy to put tourists into space - that's energy that could be tackling climate change.

Here's the problem - the worlds of policy and business are definitely waking up to the climate crisis. But some changes in the natural world appear to be outstripping society's responses.

It looks as though Mrs Thatcher was right - we needed drastic action decades ago.

Tomorrow I'll return to coolly dissecting intriguing policy issues but today with Hazel at the back of my mind, please excuse me this brief visit to my more emotional side.

In my 30+ years of reporting on the climate I've always taken a risk perspective on stories, because Mrs Thatcher was right that there's only one planet. And I want Hazel and her own future grand-children to enjoy it.

I used to employ the Twitter hashtag #Rollthedice. Now I've changed it to #Playingwithfire.