Climate change: Curbing methane emissions will 'buy us time'

- Published

An aggressive campaign to cut methane emissions can buy the world extra time to tackle climate change, experts say.

One of the key findings in the newly released IPCC report is that emissions of methane have made a huge contribution to current warming.

The study suggested that 30-50% of the current rise in temperatures is down to this powerful, but short-lived gas.

Major sources of methane include agriculture, and leaks from oil and gas production and landfills.

For decades, the main focus of efforts to curb global warming has been the ever-rising emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) from human activities, such as generating power and clearing forests.

There's been good scientific reasons for this, as CO2 is the biggest driver of temperatures responsible for around 70% of the warming that's taken place since the industrial revolution.

Methane (CH4), though, hasn't had the same focus.

That may be changing, as earlier this year, a major UN study highlighted its environmental impact.

Now, as this week's IPCC report, external points out graphically, methane's influence has been calculated as adding about 0.5C to the warming the world is experiencing right now.

So where is all this methane coming from?

Around 40% of the gas comes from natural sources such as wetlands - but the bigger share now comes from a range of human activities.

"It's a combination of sources, from agriculture, including cattle and rice production, another large source of methane is rubbish dumps," said Prof Peter Thorne, an IPCC author from Maynooth University in Ireland.

Methane bubbles up from a wetland in Sweden

"One of the biggest is from the production, transport and use of natural gas - which is really misnamed and should be called fossil gas."

Since 2008, there's been a big spike in methane emissions, which researchers believe is linked to the boom in fracking for gas, external in parts of the US.

In 2019, methane in the atmosphere reached record levels, around two-and-a-half times above what they were in the pre-industrial era.

What worries scientists is that methane has real muscle when it comes to heating the planet. Over a 100-year period it is 28-34 times as warming as CO2.

Over a 20-year period it is around 84 times as powerful per unit of mass as carbon dioxide.

However, one key positive about CH4 is that it doesn't last as long in the air as CO2.

"If you emit a tonne of methane today, in a decade's time, I would expect half that tonne to remain in the atmosphere," said Prof Thorne.

"In two decades, time, there would be a quarter of a tonne, so basically, if we managed to stop emitting methane today by the end of this century, emissions would be down to natural levels, that they were in about 1750."

In the short term, experts believe that if methane emissions were cut by 40-45% over the next decade, you'd shave 0.3C off the increase in global temperature by 2040.

In a world where every fraction of a degree counts, that's a potentially huge difference to hopes of keeping the 1.5C threshold alive.

What excites many researchers is the belief that are a range of relatively simple actions that can quickly curb the production of methane.

"It's relatively cheap to bring down some of the sources," said Prof Euan Nisbet from Royal Holloway University of London.

"In particular, I'm talking about leaks from the gas industry, which now are so much easier to find, than they were 10-20 years ago, because the instruments are so much better."

"Some things we can do quite quickly - in the tropics, you can put soil on top of these huge urban landfills and you can do a lot about stopping crop waste fires."

Quick fixes really do work. In the US, efforts to collect gas from landfill sites saw methane emissions cut by 40% between 1990 and 2016.

Collecting gas at landfill sites in the US has slashed methane from dumps

In agriculture there are also many technical changes related to manure and animal feed that can make a difference in lowering emissions.

But getting the really big cuts will require political action.

In countries like Ireland and New Zealand, where farming plays a huge role in the economy, these changes are contentious.

To succeed, they will have to be fair and equitable.

"You can't just say that people can no longer keep cattle or sheep," said Prof Thorne.

"It needs policies to aid a transition to other means of managing the land, but it is not going to happen by people pronouncing you can't keep livestock any longer, it needs to be a much more nuanced approach."

Consumer choice when it comes to dairy and meat will certainly impact this sector.

The oil and gas industry also faces a massive challenge in curbing methane.

Regulations to date have failed to stop leaks, but there's a growing interest among fossil fuel companies in using technology that can rapidly identify and stem the emissions.

"If you look at it from an objective standpoint, the industry is improving, they are improving the leaks, they are improving the number of incidents, but it's not quick enough," said Arnel Santos, a 25-year oil industry veteran with Shell and now chief operating office of energy technology company mCloud Technologies.

"We need to go faster with respect to this challenge, to really show we can quickly deploy technology to augment what they're doing, because the improvements to date will not be quick enough with what we're seeing."

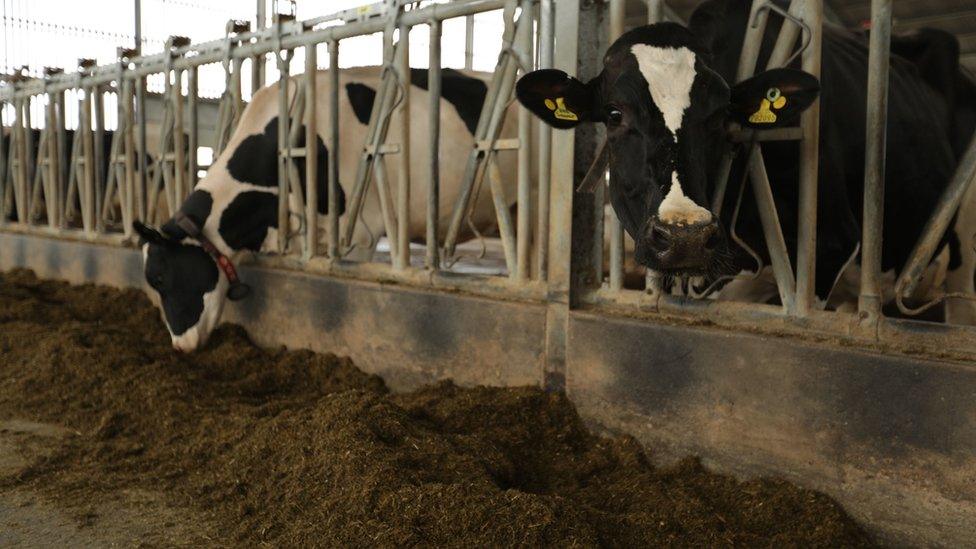

Agriculture is one of the sources of methane that is difficult to tackle

Perhaps the biggest change that's required is to separate out methane from other warming gases on the international stage.

There are worries that because UN climate negotiators deal with all greenhouse gases in the same process, there are concerns they may make trade-offs, comparisons and compromises on methane that muddy efforts to reduce these emissions.

Many are now calling for a separate process for methane, along the lines of the Montreal Protocol, that successfully brought countries together to regulate ozone-depleting gases.

"To halt long-term warming, we need to halt carbon dioxide emissions," said Prof Thorne.

"But to aid us on that path, we could treat these gases differently. And if we were to treat methane differently, it might buy us time to adapt to the changes that are occurring."

"It's carbon dioxide that absolutely needs to get to net zero. But if we are to halt long term warming, methane can absolutely help us on the way."

Follow Matt on on Twitter., external