'Perfect' James Webb telescope on track for launch

- Published

Peter Jensen: "For Europeans the cost equates to a cheap cup of coffee drunk over 20 years"

The successor to the Hubble Space Telescope is on track for a launch in mid-December, officials say.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has cost $10bn to develop and will be one of the grand scientific endeavours of the 21st Century.

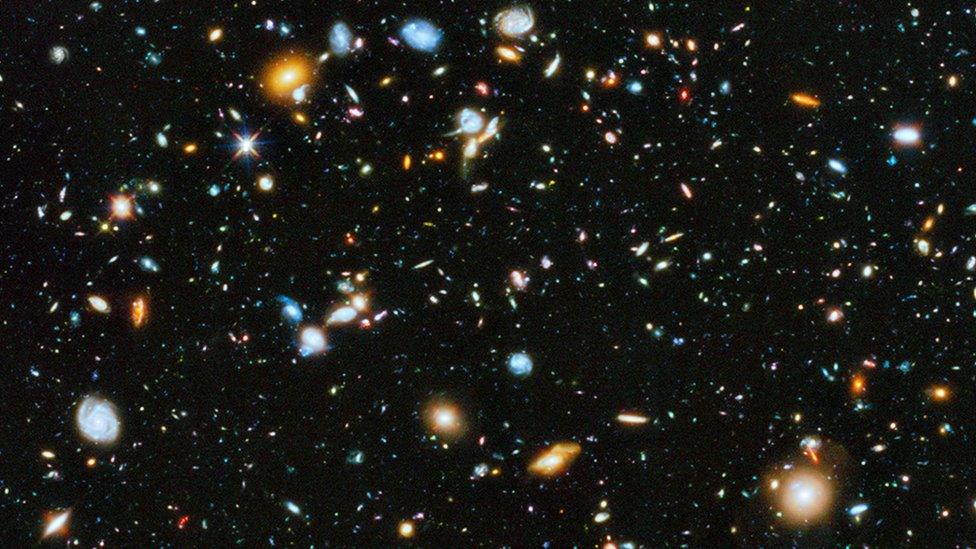

Its mission is to image the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

Webb will be sent to orbit on an Ariane rocket from French Guiana. Engineers there began assembling the vehicle's various components over the weekend.

The Ariane's 30m-tall main core stage was lifted into the vertical to allow its side boosters to be attached. The rocket's upper-stage, which will drive the latter part of Webb's ascent, will be bolted on in a few days.

JWST itself is likely to be placed atop the rocket a week before lift-off on 18 December.

The most distant galaxies seen by Webb are expected to contain pioneer stars

There's great pride here at the Kourou spaceport that Ariane was given the responsibility of sending Hubble's successor on its way.

"It's the launch of a generation," Daniel De Chambure, from the European Space Agency's (Esa) launcher directorate, told BBC News.

The new telescope arrived in French Guiana by ship in October, brought from the Californian factory where aerospace company Northrop Grumman and the US space agency (Nasa) had overseen final integration.

The Ariane rocket's core stage was lifted into the vertical on Saturday

Once off the ship, JWST received a detailed examination to confirm no damage had occurred in transit.

"We've checked everything over and I can report James Webb is in perfect condition," said Nasa instrument systems engineer Begoña Vila.

In its cleanroom in Kourou, the telescope stands on its end. It's been folded from its operational configuration to enable it to fit inside the nosecone of the Ariane. Even so, it towers over the technicians keeping watch.

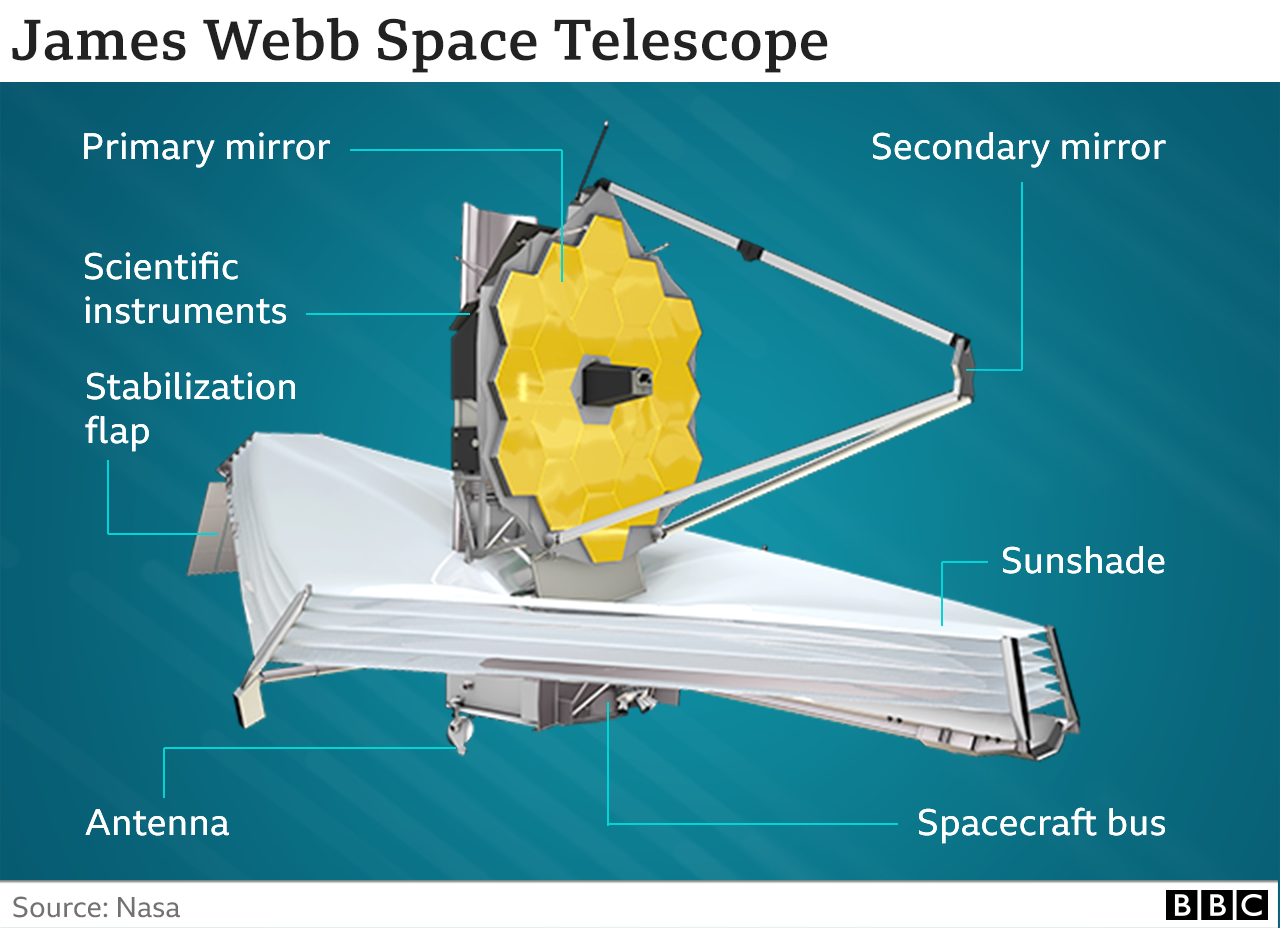

They continue to maintain a rigorous cleaning campaign, ensuring the environment around Webb is spotless. Two filtration walls pull dust away from the telescope. The bunny-suited workforce are also constantly wiping down the floor and the surfaces of support equipment to further guarantee no contamination taints the gold-coated segments that make up Webb's 6.5m-wide mirror.

It's all now about making sure Webb goes to the launch pad in perfect condition

Tuesday's duties will see the preparation team lift JWST on to its launch adaptor. This is the ring that will hold it to the top of the rocket.

Lasers will guide the procedure. It's then a case of fuelling Webb and mating it to the Ariane upper-stage via the adaptor.

A tricky event will be encapsulation, when the rocket's nosecone is lowered over the telescope. There'll be very little clearance, especially when the whole structure is shaking back and forth during the 30-minute ride to space.

"Statically, we're only 6-8 inches (15-20cm) from the edge of the fairing, but under launch loads we come within 3.5 inches (9cm). It's very close, so we need to be very precise about everything," said Nasa's launch site manager, Mark Voyton.

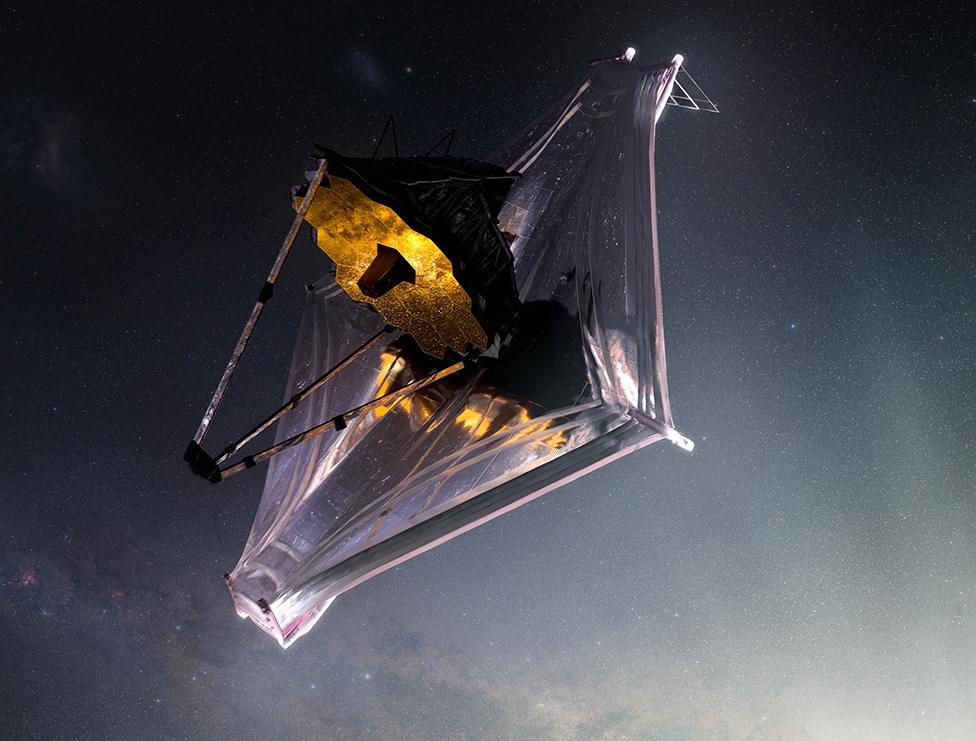

Webb is an astonishing construction to see in the cleanroom.

It's a blaze of gold and silver, the latter colour represents layers of insulation. The slight purple hue comes from a silicone treatment that enhances reflectivity.

But it's the size that takes your breath away, and that's just in the folded, launch configuration. When in orbit, deployments will extend the observatory to about the size of a tennis court.

Kourou launch director Jean-Luc Voyer rehearses his Webb countdown

JWST's mirrors and state-of-the-art instruments have been tuned to see the glow from the very first stars to shine in the Universe, an event theorised to have occurred about 200 million years after the Big Bang (just over 13.5 billion years ago).

The telescope will also have the power to resolve the atmospheres of many of the new planets now being discovered beyond our Solar System, and to analyse their gases for the possible presence of biology.

Much has been made of the project's cost, most of it borne by Nasa. But for Europe, too, the investment has been large - but well worth it, says long-time Esa project manager Peter Jensen.

"On face value there's a lot of zeroes, and Europe has spent €700m (£600m; $800m) on this mission. But when you look at it as a cost per inhabitant in Europe, it comes down to a cheap cup of coffee in a cheap cafe, drunk over a period of 20 years. And for that we get access to such a high-performance observatory that will take us on a kind of Columbus journey to an unknown period in cosmic history."

Even in its folded configuration, Webb is huge