James Webb telescope parked in observing position

- Published

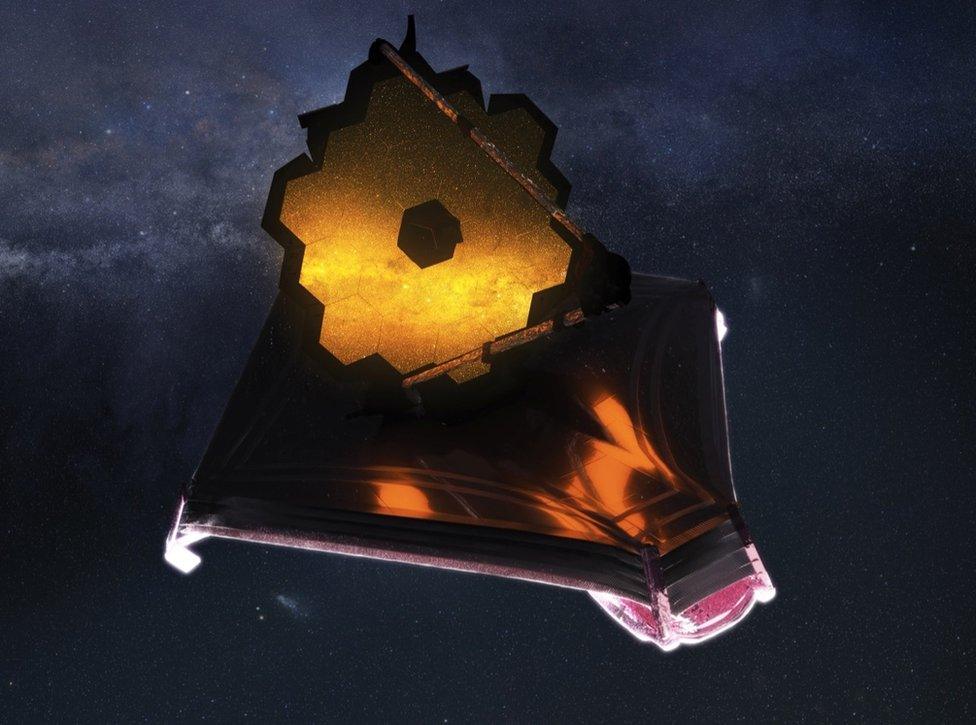

Artwork: Webb should be ready for full science operations in June or July

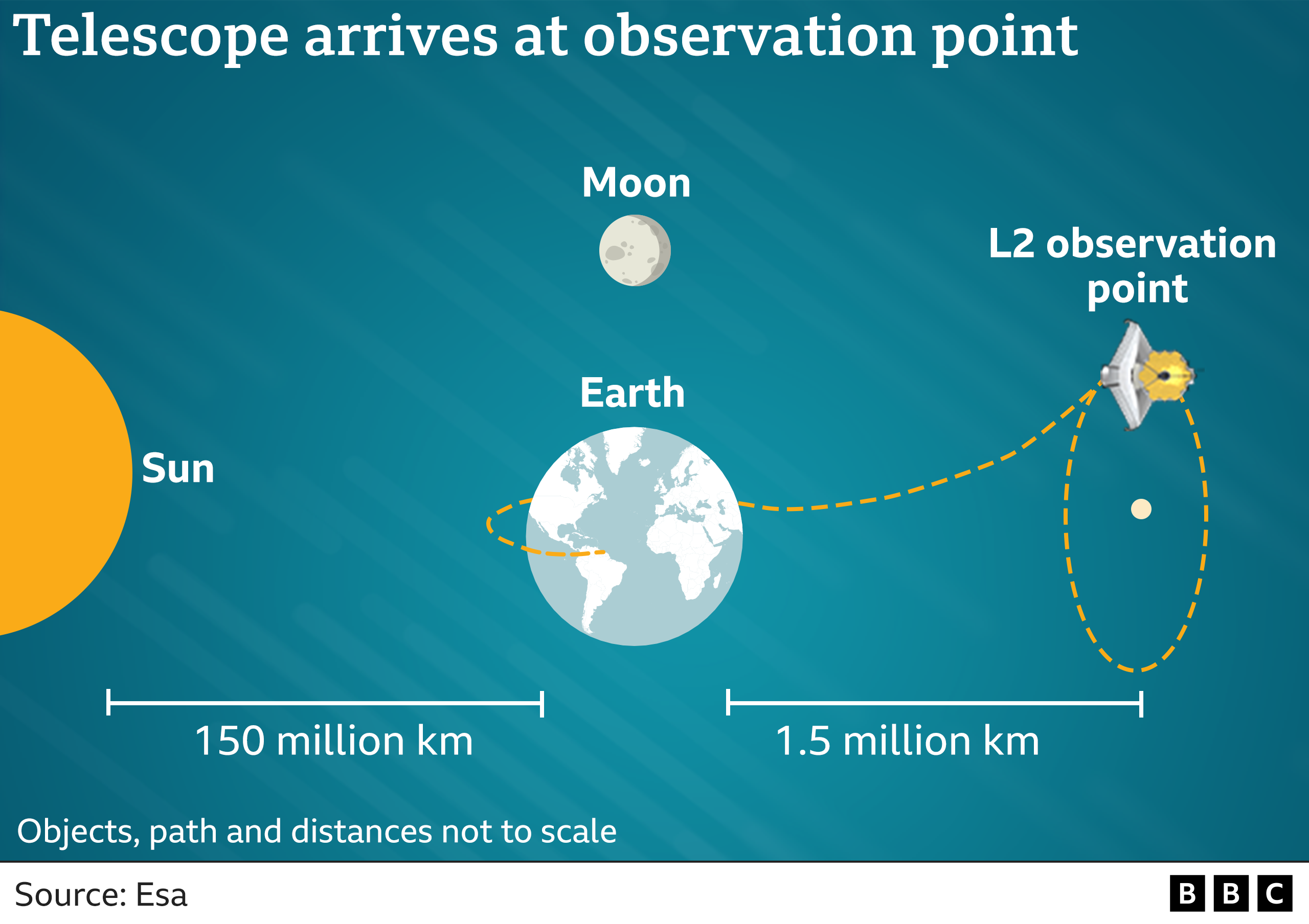

Thirty days after it was launched, the James Webb telescope has arrived at the position in space where it will observe the Universe.

The Lagrange Point 2, as it's known, is a million miles (1.5 million km) from Earth on its nightside.

Webb was finally nudged into an orbit around this location thanks to a short, five-minute thruster burn.

Controllers back on Earth will now spend the coming months tuning the telescope to get it ready for science.

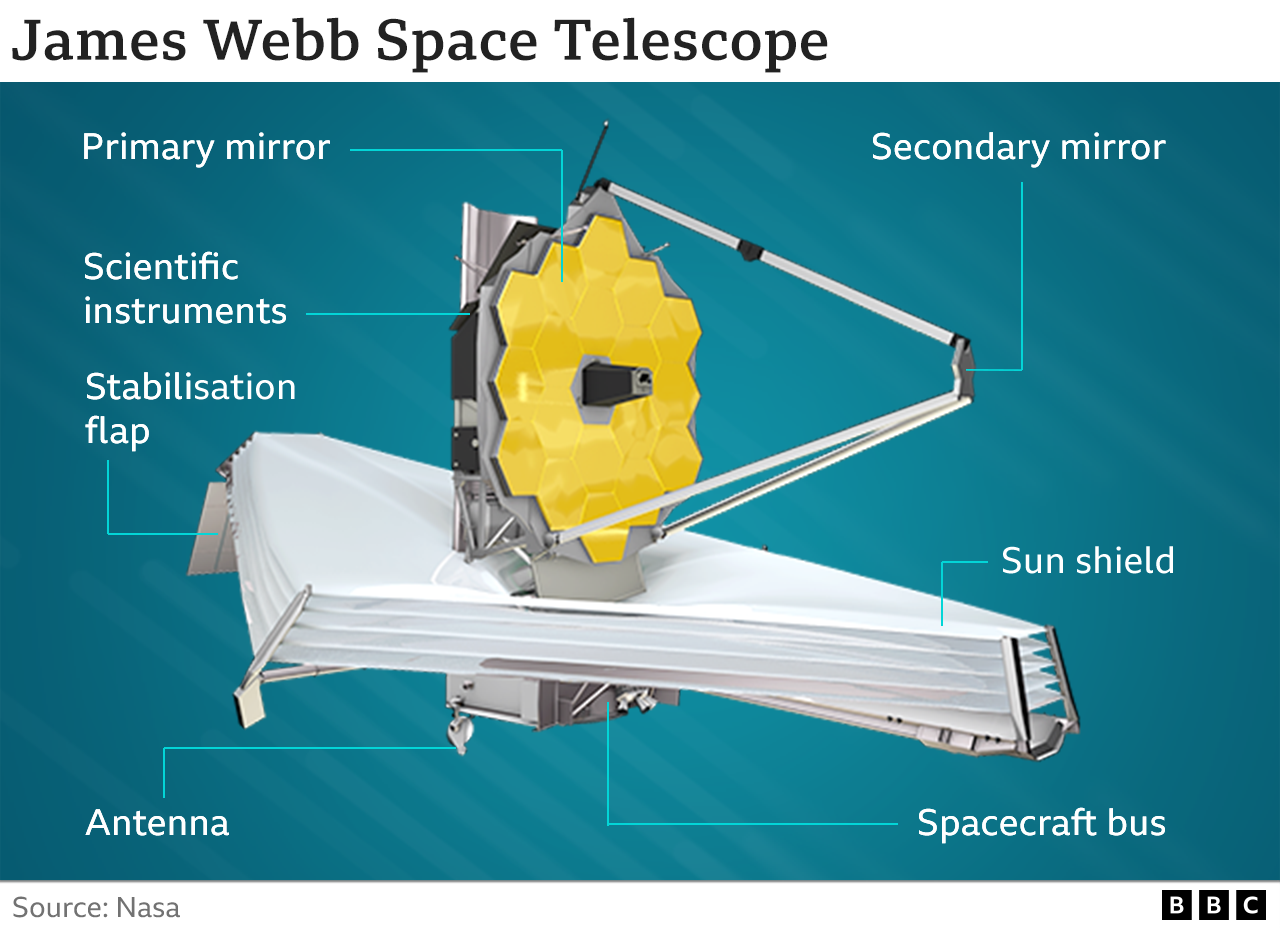

Key tasks include switching on the observatory's four instruments, and also focusing its mirrors - in particular, its 6.5m-wide segmented primary reflector.

"There's a pretty intensive effort to take all of those 18 segments from their current state and get them to act as one big mirror, and also to get the secondary mirror into its optimised condition," explained Charlie Atkinson, the chief engineer on Webb at Northrop Grumman, the American aerospace company that co-led the telescope's development with the US space agency (Nasa).

"We do this using the science images, which is why we need to get the science instruments activated and checked out with some initial calibration work," he told BBC News.

Webb, billed as the successor to the famous Hubble Space Telescope, was launched on 25 December by an Ariane-5 rocket from French Guiana.

Its overarching goals are to take pictures of the very first stars to shine in the Universe and to probe far-off planets to see if they might be habitable.

Europe's Ariane-5 gave the new observatory a near-perfect trajectory and velocity to get it out to L2. Even so, two course correction burns were necessary, with the third on Monday tipping Webb into its planned parking position.

Lift-off: Watch the moment the James Webb left Earth on its Ariane rocket

The Lagrange Point 2 is one of five gravitational "sweet-spots" around the Sun and Earth where satellites can hold their position with few orbital adjustments, thus conserving fuel.

The other advantage is that Webb will not experience at L2 the big swings in temperature and light endured by space telescopes positioned much closer to Earth.

This is vital for the mission. It's designed to view the cosmos in infrared light and must maintain therefore constant super-cold conditions for its hardware.

Infrared light has waves that are just longer than those of visible light. "Seeing" in the infrared will allow the telescope to, for example, look through dust to image stars that would otherwise be obscured.

The individual segments of the primary mirror must be aligned to act as one

Webb will now circle L2, keeping the Earth and the Sun in a near-straight line.

"L2 is pseudo-stable," said Jean-Paul Pinaud, who leads the Northrop engineers that keep Webb on track.

"The flight operations team is preparing routine station-keeping burns. They'll be doing those every 20 days or so with the trajectory calculations provided by our flight dynamics team. We'll set them up in a similar way, and then fire the thruster. But the burns will be quite small."

Hidden behind a big sunshield, Webb's optics and instruments will soon cool to about -230C (some sections of the telescope are already there). When that happens, controllers will switch on Webb's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) to take a picture of a test star to begin the process of aligning the big mirror.

"We know when we first focus on a star in space, we'll actually see 18 different spots of light because the 18 individual mirror segments won't be aligned," said Nasa instrument systems engineer Begoña Vila.

"But we'll adjust the mirrors to bring all the spots together to make a single star that's not aberrated and good for normal operations.

"It's a long process. It can take up to three months during commissioning, and we are ready to do that," she told BBC News.

Focusing involves driving small actuators, or motors, on the back of the 18 segments of the primary mirror to harmonise their curvature. The current misalignment, which is measured in millimetres, will be brought down to one measured in nanometres - a factor of a million improvement.

Similar adjustments will be applied to the 74cm-diameter secondary reflector which sits out in front of the primary mirror and is used to bounce light back towards the instruments.

An image taken from the top of the Ariane as Webb separates to begin the next phase of its journey

So far, the Webb mission has not put a step wrong. The launch and journey out to L2 passed off without incident.

And even the complex business of unfolding the telescope after it came off the top of the Ariane rocket was made to look like the easiest of rehearsals.

"We were thrilled with the precision and success of all those deployments," said Kyle Hott, the mission systems engineering lead at Northrop.

"It's pretty incredible to think that it was all just a concept on paper decades ago, and now it's actually here, arriving at L2. Morale is high and we're so very excited."