Antarctic: Giant iceberg breaks away in front of UK station

- Published

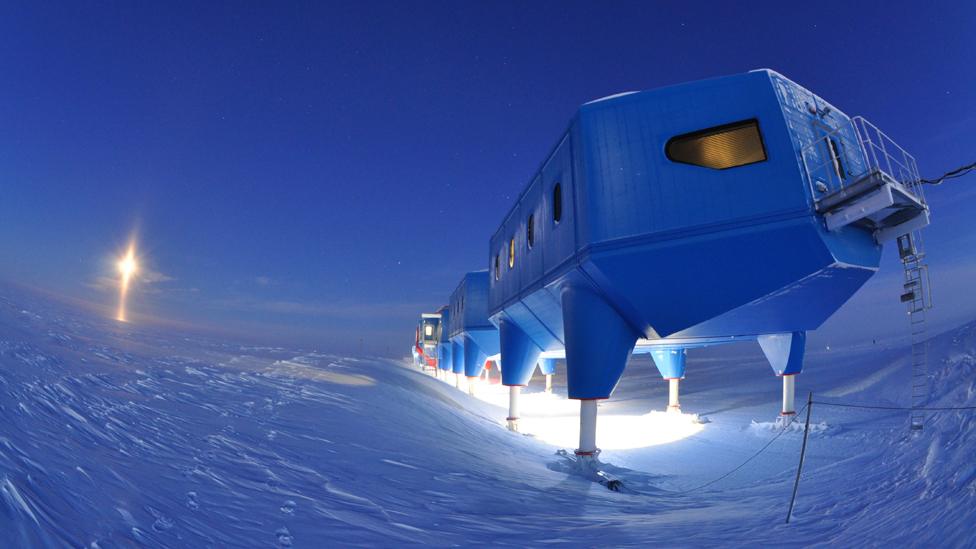

An archive photograph of the leading edge of the ice that's broken away

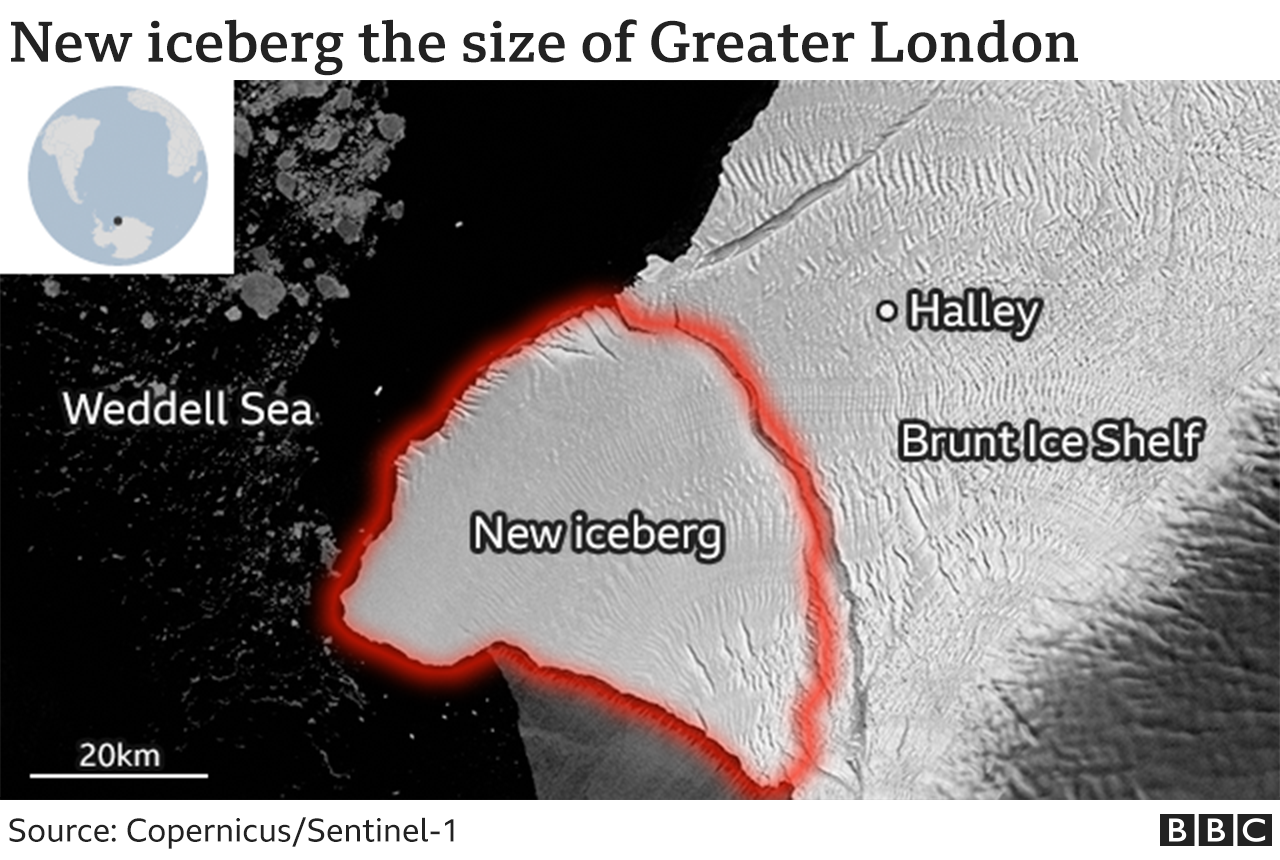

A big iceberg roughly the size of Greater London has broken away from the Antarctic, close to Britain's Halley research station.

Sensors on the surface of the Brunt Ice Shelf confirmed the split late on Sunday GMT.

Currently, 21 staff are at Halley, maintaining the base and operating its scientific instruments.

They are not in any danger and will continue their work until they're due to be picked up early next month.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) has been operating the station in a reduced role in anticipation of the calving.

Halley is positioned a good 20km from the line of rupture.

BAS has an array of GPS devices in the area that relay information about ice movements back to the agency's HQ in Cambridge.

The UK has had a research station on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1957

Officials will be inspecting satellite imagery when it becomes available. They will want to see that no unexpected instabilities emerge in the remaining ice shelf platform that holds Halley.

A similar sized berg, known as A74, calved in February 2021 further to the east. At the time, it was thought that its departure might initiate the latest breakaway, but these events are beyond any confident prediction.

This is the area known to have calved, which up-to-date satellite imagery should confirm

Where exactly is this?

It is on the Brunt Ice Shelf, which is the floating protrusion of glaciers that have flowed off the Antarctic continent into the Weddell Sea. On a map, the Weddell Sea is that sector of Antarctica directly to the south of the Atlantic Ocean. The Brunt is on the eastern side of the sea. Like all ice shelves, it will periodically calve icebergs. Prior to this latest berg and A74, the last major chunk to come off the Brunt was in 1971.

Was the breakaway anticipated?

Absolutely. Just not its timing. Scientists continuously monitor any major cracks in the Brunt, and had noticed one particular split - dubbed Chasm One - start to open up again after decades of dormancy. Recent years had seen the propagation of Chasm One accelerate, resulting now in the complete separation of a block of ice that is about 150-200m thick.

Chasm One is the main line of rupture along the ice shelf

What now for Halley station?

The British base consists of a series of modules on skis that enable it to be moved away from the leading edge of the ice shelf. When Chasm One was seen to come back to life, the decision was taken to shift Halley 23km "upstream" - a task completed in early 2017. Had that relocation not taken place, Halley would now be sitting in a very dangerous position on the breakaway iceberg.

What of people in the area?

During Antarctic winters, BAS had been removing all its staff from Halley. It didn't want to be in the position of having to evacuate people during a time of year when the polar night lasts 24 hours and weather conditions can be atrocious. It's currently the Austral summer, so if the small crew presently at the station needed to be removed, it could be done quickly and safely.

Just how big is the new berg?

Estimates put it at around 1,550km² - nearly 600 square miles. That's big by any measure. It's city-sized. The job of naming icebergs falls to the US National Ice Center. Because the new block is in the Antarctic quadrant that runs from 0 degrees longitude to 90 degrees West, it will carry the letter "A" in its designation. It's likely to be called A81. The "81" refers to its place in the sequence of major calvings in the region. The similarly sized berg that broke away from the Brunt to the east of Halley was called A74.

The McDonald Ice Rumples helped pin and stabilise the ice

What happens next?

The calving of large bergs from a shelf structure can lead to a speed-up in the flow of the ice. Before the calving, the Brunt was flowing westwards at a rate of about 3m/day. If it now experiences an acceleration, this could influence the behaviour of other cracks in the area. In particular, scientists are watching very closely a fissure they call the Halloween Crack. This is sited to the north and east of Halley, and is propagating away from the base. The researchers will want to observe its reaction, if any. Much will depend on what happens at the so-called McDonald Ice Rumples - a raised area of seafloor that catches the underside of the Brunt shelf and ordinarily helps pin it in place.

Is this climate change in action?

No. The calving of bergs at the forward edge of an ice shelf is a very natural behaviour. The shelf likes to maintain an equilibrium and the ejection of bergs is one way it balances the accumulation of snowfall and the input of more ice from the feeding glaciers on land. Unlike on the Antarctic Peninsula on the other side of the Weddell Sea, scientists have not detected climate changes in the Brunt region that would significantly alter the natural process described above. What is more, estimates suggest the Brunt was at its biggest extent in at least 100 years before the calving. The famous explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton recorded a much smaller shelf structure when he passed by on his ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914-1917. A significant calving was certainly due.