Lab-grown brain cells play video game Pong

- Published

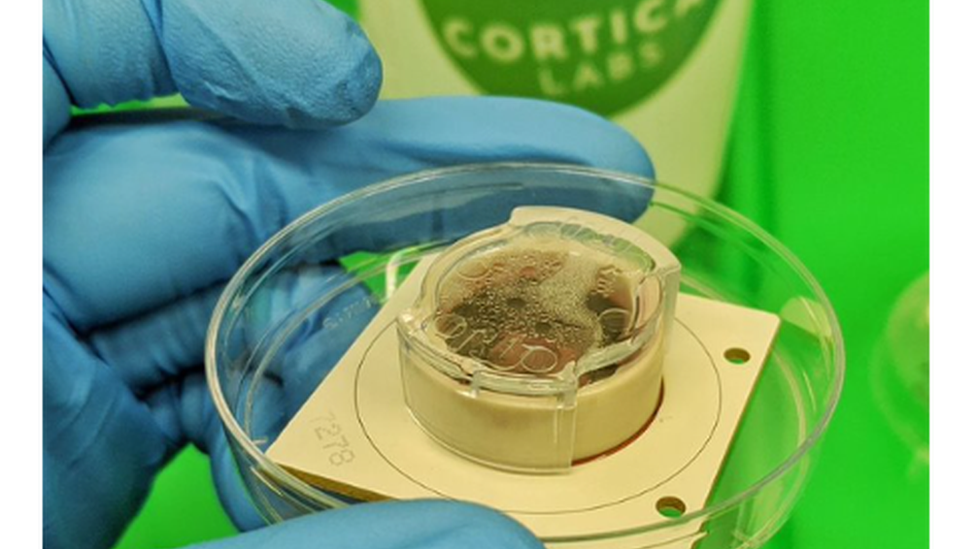

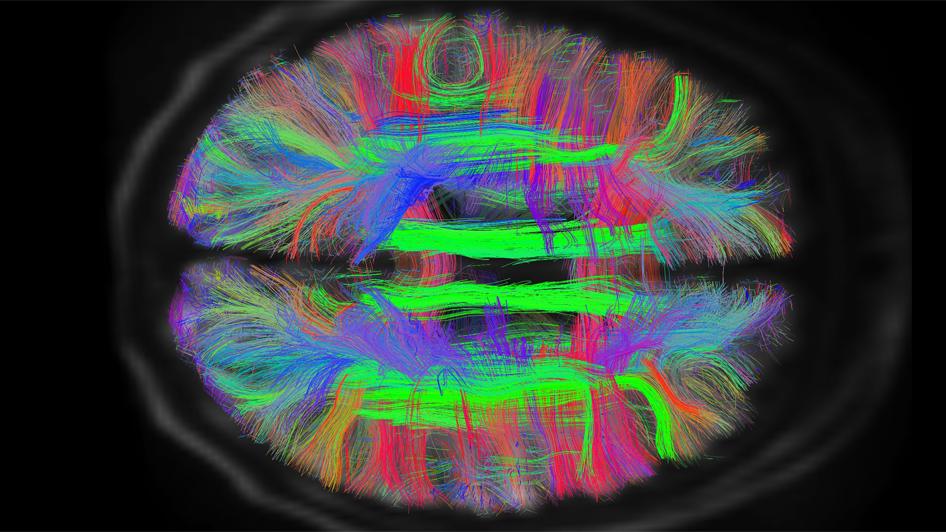

These 800,000 lab-grown brain cells can play a 1970s video game, albeit badly

Researchers have grown brain cells in a lab that have learned to play the 1970s tennis-like video game, Pong.

They say their "mini-brain" can sense and respond to its environment.

Writing in the journal Neuron,, external Dr Brett Kagan, of the company Cortical Labs, claims to have created the first ''sentient'' lab-grown brain in a dish.

Other experts describe the work as ''exciting'' but say calling the brain cells sentient is going too far.

"We could find no better term to describe the device,'' Dr Kagan says. ''It is able to take in information from an external source, process it and then respond to it in real time."

The human brain is more adaptable and learns faster than current artificial-intelligence (AI) systems. Could it be a better model for the next generation of computers?

Mini-brains were first produced in 2013, to study microcephaly, a genetic disorder where the brain is too small, and have since been used for research into brain development.

But this is the first time they have been plugged into, and interacted with, an external environment, in this case a video game.

The research team:

grew human brain cells grown from stem cells and some from mouse embryos to a collection of 800,000

connected this mini-brain to the video game via electrodes revealing which side the ball was on and how far from the paddle

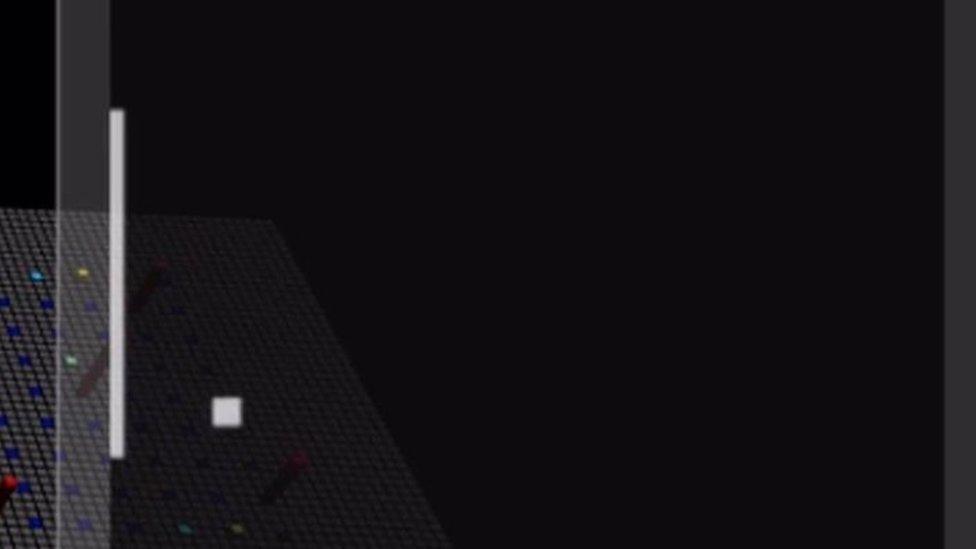

Pong is an early computer game where the object is to move the bar on the left to prevent the small square slipping past - very simple, but very exciting in 1972

In response, the cells produced electrical activity of their own.

They expended less energy as the game continued.

But when the ball passed a paddle and the game restarted with the ball at a random point, they expended more recalibrating to a new unpredictable situation.

The mini-brain learned to play in five minutes.

It often missed the ball - but its success rate was well above random chance.

Although, with no consciousness, it does not know it is playing Pong in the way a human player would, the researchers stress.

Beer Pong?

Dr Kagan hopes the technology might eventually be used to test treatments for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's.

"When people look at tissues in a dish, at the moment they are seeing if there is activity or no activity. But the purpose of brain cells is to process information in real time," he says. "Tapping into their true function unlocks so many more research areas that can be explored in a comprehensive way."

Next, Dr Kagan plans to test the impact alcohol has on the mini-brain's ability to play Pong.

If it reacts in a similar way to a human brain, this would underscore just how effective the system might be as an experimental stand-in.

The researchers say their mini brains are more adaptable than current AI systems and so might provide the basis for more adaptable robots

Dr Kagan's description of his system as sentient, however, differs from many dictionary definitions, which state it means having the capacity to have feelings and sensations.

Cardiff Psychology School honorary research associate Dr Dean Burnett prefers the term ''thinking system''.

''There is information being passed around and clearly used, causing changes, so the stimulus they are receiving is being 'thought about' in a basic way,'' he says.

The mini-brains are likely to become more complex as the research progresses - but Dr Kagan's team are working with bioethicists to ensure they do not accidentally create a conscious brain, with all the ethical questions that would raise.

"We have to see this new technology very much like the nascent computer industry, when the first transistors were janky prototypes, not very reliable - but after years of dedicated research, they led to huge technological marvels across the world," he says.

Artificial-intelligence (AI) researchers have already produced devices that can beat grandmasters at chess.

But Prof Karl Friston, of University College London, who is working with Dr Kagan, says: "The mini-brain learned without it being taught and so is more adaptable and flexible."

Hear more from the team behind this breakthrough on Inside Science on BBC Sounds.

Follow Pallab on Twitter., external

Related topics

- Published17 February 2013

- Published27 May 2015

- Published29 June 2017