COP27: Why the latest UN climate conference matters

- Published

Tens of thousands of people will be jetting to an Egyptian holiday resort beside the Red Sea this weekend in an effort to tackle climate change.

It sounds like a joke, but this latest UN climate summit - COP27 - is reckoned to be the world's best hope of progress on the climate issue.

Progress is certainly needed.

The global effort to cut emissions is "woefully inadequate" and means the world is on track for "catastrophe", the UN warned last week.

But the meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh is shaping up to be a prickly and confrontational affair.

Cash for climate change

The Egyptian hosts have set themselves a tough challenge.

Last year's UN climate conference in Glasgow delivered a host of pledges on emissions cuts, finance, net zero, forest protection and more.

Egypt says their conference will be about implementing these pledges.

What that really means is it will be all about cash, and specifically getting wealthy nations to come good on their promises of finance to help the developing world tackle climate change.

So expect the main battle lines to be between the north and south, between rich and poor nations.

Leaders heading to the Red Sea resort of Sharm El-Sheikh face a tough challenge

"Don't underestimate how angry developing nations are," Antonio Guterres, the UN chief, told me when I met him last week.

He says they feel high-income countries have welched on the landmark deal made at the UN climate conference in Paris in 2015.

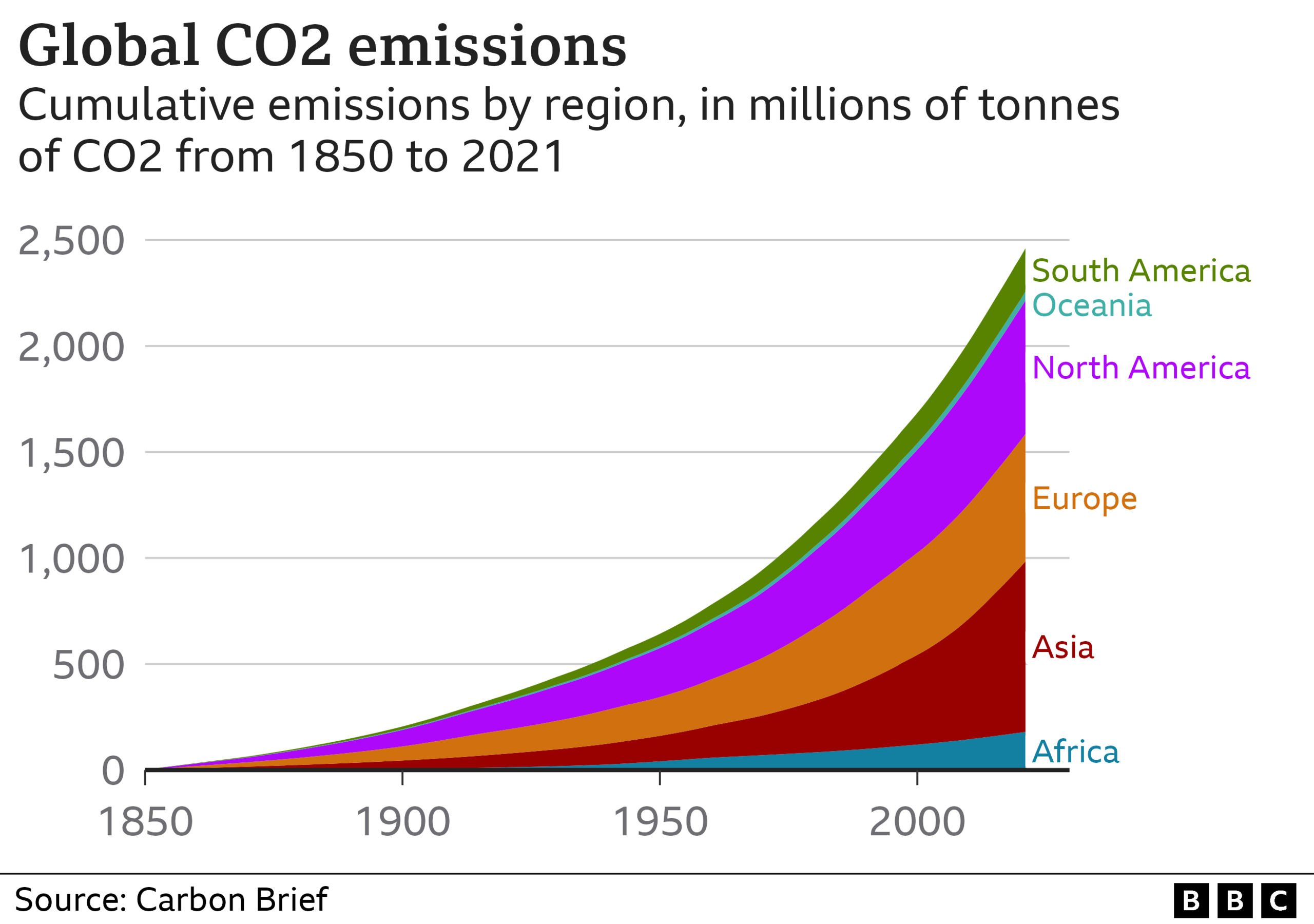

Paris was a breakthrough because for the first time developing countries accepted the worst impacts of climate change could only be avoided if they too cut carbon emissions. Before that they had argued they didn't cause the climate problem: so why should they help fix it?

In return, the wealthy world agreed to help fund their efforts.

The problem is it hasn't honoured that commitment.

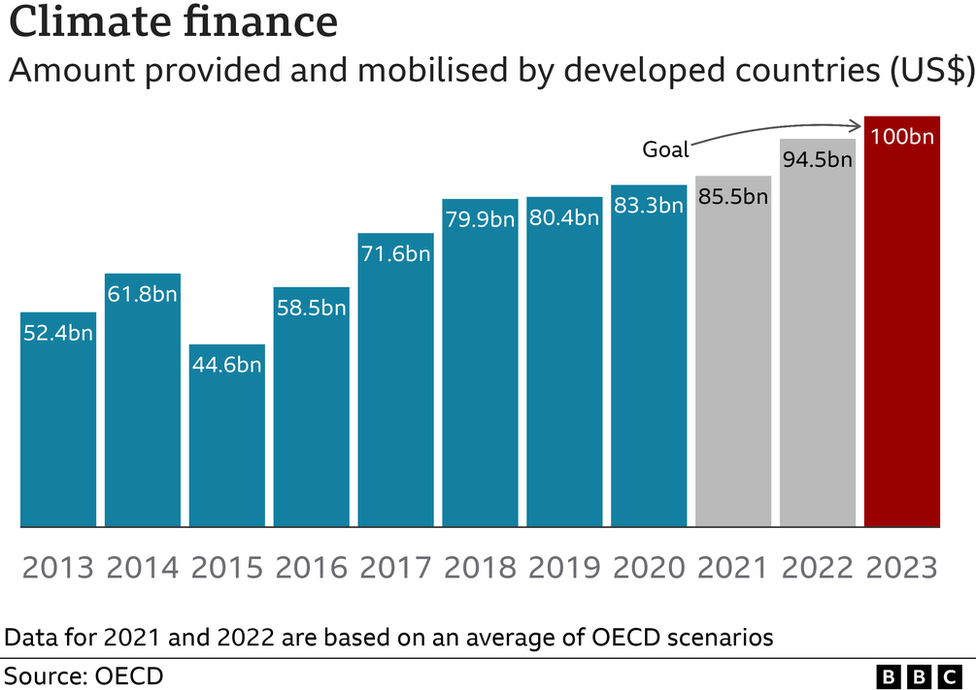

Top of Egypt's "to-do" list is the $100bn (£89bn) a year developed countries promised way back in 2009 to help the developing world cut emissions and adapt to our changing climate.

It was supposed to be delivered in 2020 but now won't be available in full until next year - three years late.

Pakistan, which suffered terrible floods earlier this year, is demanding the developed world also agrees on a funding mechanism to compensate for the loss and damage climate change is already causing in developing countries.

It brings real heft at the talks as chair of a key UN grouping of 134 developing countries, including China.

"I don't think it is an impossible ask," the Pakistani climate minister, Sherry Rehman, told the BBC this week. Just look how much money the world finds to fund wars, she said.

The stakes are high. Egypt has warned of a "crisis of trust" if progress on loss and damage isn't made, Mr Guterres has described it as the "litmus test" of the conference.

But expect strong pushback from developed countries

Europe and the US have agreed there should be a formal discussion of the issue but are unlikely to make commitments of cash.

They worry the costs will spiral into trillions of dollars as the impacts of climate change get more severe in years to come.

And the backdrop of soaring food and energy prices and rising interest rates following the Russian invasion of Ukraine means many developed countries are focusing on their own economic woes.

Meanwhile, the chill in relations between the US and China is set to amplify any conflicts in Egypt.

Internally displaced people crossing a flooded area by boat in Pakistan

In the past, the two superpowers have played a crucial role quietly helping broker compromises in the background.

But China ended its policy of keeping climate negotiations separate from other issues after Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic speaker of the US House of Representatives, visited Taiwan in August.

But you can expect lots of discussion about addressing loss and damage in other ways.

Egypt wants to strengthen weather and climate forecasting across the developing world so countries can prepare better for weather extremes.

There is a German proposa, externall for an insurance-based "Global Shield" scheme to help poor countries recover faster from climate disasters that already has considerable support.

You may also see progress with debt relief. Soaring borrowing costs make the huge debts many developing countries have even less affordable, leaving less money for tackling climate change and its impacts.

There will also be a concerted push to accelerate emissions cuts. The US climate envoy, John Kerry, has told the BBC this remains the US priority.

But only 24 out of 193 countries updated their carbon cutting ambitions this year, leaving the world on track for temperature rises of 2.7C.

Mr Kerry says "lots of countries" are now contributing to the damage - a reference to the fact that many countries classified as developing are now major sources of CO2. China is now the world biggest emitter, for example, India the third biggest.

Your device may not support this visualisation

But there will be resistance from some developing countries.

The Egyptians want to have natural gas classified as a "transition" fuel, part of a broader effort, supported by many African nations, for low-income countries to be allowed to develop their fossil fuel reserves.

The British prime minister, Rishi Sunak, announced this week he will now be joining more than 100 other world leaders, including President Biden, to open the talks.

Greta Thunberg, however, is among the list of those who will not attend.

She described the global summit as a forum for "greenwashing" this week, saying the COP conferences "encourage gradual progress".

Greta Thunberg will not be attending

It is a familiar criticism. The UN process is slow and cumbersome and far from perfect but, as Sherry Rehman says, it is all we have.

The actual negotiations are carried out by the army of diplomats and civil servants who are already flying in to Sharm El-Sheikh.

They will be steeling themselves for some intense discussions.

If they want to remind themselves of what is a stake, they should take a swim over the coral reefs that lie just off the coast.

The world's reefs are under attack from rising ocean temperatures, according to scientists, external, with 14 per cent lost just in the decade to 2018.

The good news is the Egyptian reefs appear to be particularly resistant to marine heating, according to local scientists.

The negotiators will need to summon similar reserves of resilience if progress is going to be made at the conference.

Top image from Getty Images. Climate stripes visualisation courtesy of Prof Ed Hawkins and University of Reading.