Doctors wouldn’t let my sister die

- Published

In 2009, Polly Kitzinger was in a car crash that left her with devastating brain injuries. Her sister, Jenny, says Polly would have preferred not to have had the medical interventions that kept her alive, but her family was unable to persuade doctors to let her die. Jenny is now a passionate advocate of living wills, or "advance decisions".

You always knew when Polly was in the room and you always knew what Polly thought. She was very persistent and passionate about what she believed. Some of us might have even called her stubborn. Hey, we come from a family like that. But even within my family, Polly stood out.

Polly was a disability rights activist. She worked with people who'd often lost the capacity to make their own decisions about medical treatment because of mental illness and she was a passionate advocate for people's own voices, values and choices being heard.

And she absolutely reserved her right to make her own unwise decisions as well. You couldn't say to her: "Well, I'm sure it's in your best interest to stay at university, or not to sail across the Atlantic in midwinter," or whatever it was. She took a lot of risks and it's a comfort that she lived life to the full and on her own terms until her car crash in 2009, when she was 48.

Find out more

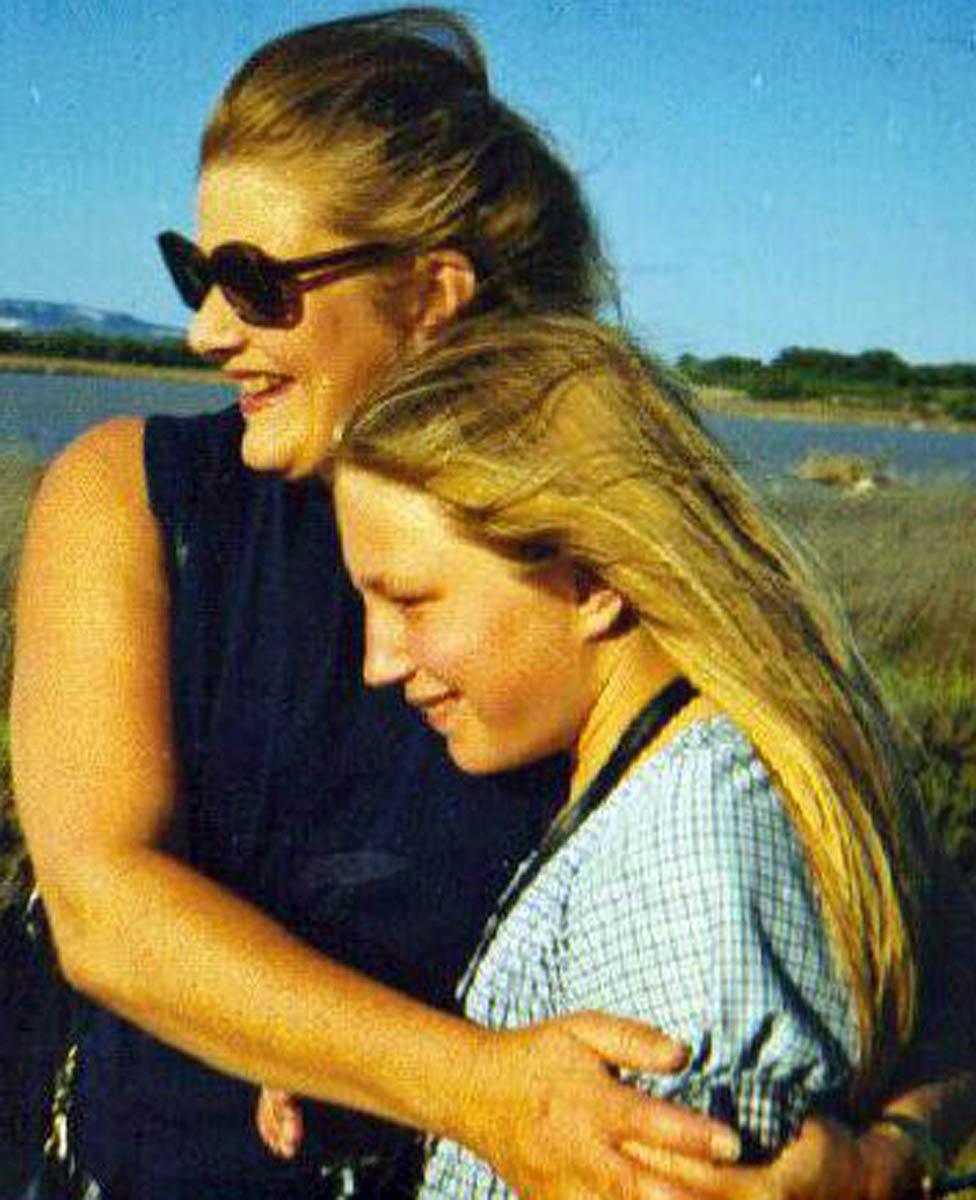

Polly and Jenny Kitzinger

• Prof Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre, external, Cardiff University

• The centre studies the care given to patients in vegetative or minimally conscious states, and how best to ensure that wishes of incapacitated patients are respected

• She was speaking to PM on BBC Radio 4 - you can listen again on iPlayer

It was clear fairly early on with Polly that she would never leave 24/7 care and it was highly unlikely that she'd ever be able to make her own choices about her life ever again.

In the early months there was nothing, no signs of awareness at all. Then she did pass from a vegetative into a minimally conscious state and everyone agreed she was experiencing pain, which they did their best to manage, and that she was experiencing distress and confusion in her moments of alertness. There were clear moments where, for a moment you'd think: "Oh, yes, she recognises me." Or maybe she'd laugh and then another time she'd cry or moan. There were many months of moaning.

We, as her family, told the doctors that Polly, whom we'd known for almost half a century, wouldn't want life-prolonging treatment - at that stage, during the first two years, this would have meant withdrawing the feeding tube.

Either they didn't listen or they just kept telling us: "It's too early. We need to give her more time to emerge. We don't yet know whether she'll stay permanently vegetative or permanently minimally conscious." Or they maybe just didn't trust or believe us, because so many people would want to be given longer and many people would want to survive longer to see if they could regain full consciousness.

Polly wasn't one of those.

Polly (left) with Jenny, around 1973

We tried to convince them. I went through all the letters I had from Polly, the backs of envelopes, the poetry she'd written, her diary entries and we found some lovely stuff. A poem she'd written about always wanting to carry her own backpack and make her own choices. A statement about her expectation that she was going to die young somewhere beautiful - and how that, for her, would be avoiding something that she might not want. It was almost prophetic.

She had started off doing a bit of philosophy at university, and I had letters she'd written to me about "I think, therefore, I am," and the importance of her mind to her identity. So we took all that in. I also wrote to everyone who was close to Polly and asked them to write a statement about what they thought Polly valued and I produced a 50-page dossier for the doctors and handed it in with a with a summary analysis at the start. And so we tried all that.

The doctors didn't know what to do with it.

They didn't seem to understand that even if there's no advance decision, you have to justify why you're giving someone treatment. If you can't justify it, and they haven't given consent, then it's assault. So you're meant to make sure you understand this patient and what they would've wanted, insofar as that's possible. This is all spelt out in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and in guidelines from the Royal College of Physicians and the British Medical Association. So you talk to family or friends and try and get a really holistic picture of that person's values and beliefs and feed that into your "Best Interests" decision.

What is an advance decision?

• An advance decision, external (sometimes known as a living will) is a legally binding decision to refuse a specific type of treatment in the future if you lose capacity to make the decision for yourself at the time

• People in Scotland can make an advance directive, external

• Advance statements, external are non-legally binding statements that sets down your values, wishes preferences and beliefs regarding your future care

Source: NHS, external

Polly was in the vegetative and then minimally conscious states for about two years. Since then she has been fully conscious, but her brain injuries have left her permanently dependent on 24/7 care for all her needs. She is unable to control her own environment, lacking the mental processing ability even to push a call button for help and the capacity to make her own choices about medical treatment.

The law has been clarified since 2009 when Polly had her car crash, and the courts have made absolutely clear now with rulings like the Paul Briggs case that, if there isn't an advance decision, it doesn't mean the person has no wishes to be considered. This is something that Prof Celia Kitzinger, my sister and co-director at the Coma and Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre, and I have written about, external. We've analysed and documented the clear direction of travel towards more person-centred "Best Interests" decision-making.

The irony is I already knew about advance decisions - Polly had told me about them and was in favour of them. We were brought up by a mother, Sheila Kitzinger, who was passionate about control over one's own body and one's own life, particularly in relation to medicine, because of her campaigning around childbirth, so it was something as a family we were aware of.

Polly with her mother in 1992

My mother already had an advance decision before Polly's accident - one that Polly had helped her write. But of course, Polly's mistake, like many of ours, was to think that only people who are older need advance decisions.

Whereas actually, of course, as we discovered with Polly, it's the people who aren't expected to die soon who need advance decisions most - it's people who are in a car crash in their 20s or 30s or 40s, in my view. This is something you can do in an afternoon. Compassion In Dying, external, for example, has a lovely online form that just takes you through, step by step, the sort of criteria that for you are key to any decision to prolong your life or not - whether you feel you can tolerate a lot of pain, for instance, whether it's important that you can recognise your loved ones, whether you can make your own choices.

There's this sense that it's all too difficult and: "Oh, well, I'd rather tile my bathroom or go for walk." So what I always say is: Don't just do this for yourself, do it for your family and also your clinical team who will be much happier knowing they're giving you the treatment that you want and not the treatment that you don't want. At the Centre, we've spoken to almost 100 family members now who've had relatives in a vegetative or minimally conscious state, and their message is: "I wish my son or daughter, husband, wife, or mother had written down their wishes."

I recognise that there's a fear among some people that family members might just be bumped off because they're inconvenient. Polly's consultant did say to me that she never trusted a family until she'd worked with them for a year or more. But what that meant was that there was no voice for Polly because families are not to be trusted until you get to know them.

So that again comes back to why it's so important that you as a person who might lose capacity should record a value statement about what you want - and if you wanted to be legally binding, write an advance decision.

Sheila and Polly Kitzinger, circa 1976

My mother was utterly devastated by what happened to Polly. I think it was a huge shock - to not be able to protect your daughter from something that you so clearly knew she would not want. And as a feminist who had achieved worldwide change for women in childbirth, and someone who was hugely powerful, to be rendered a mother unable to protect your daughter - it was unbearable.

Sheila's advance decision was very particular to Sheila. One of her very clearly expressed wishes was that she wanted to die at home. She did not want to be transferred to hospital and that's not necessarily a wish I agree with. I don't think for everybody in every situation that home is the best place to die. But it was certainly Sheila's view for herself and she was very passionate about that.

Her death was a good death. When you've seen prolonged end-of-life stages maintained by medical interventions that someone wouldn't want, you really know what a good death is. She was able, almost until the end, to make her own requests and choices. She had a view out of a window, of trees. Her pain and her symptoms were well-managed. She had just finished her autobiography, and as she died, we were reading the proofs to her, so that was very fitting.

Polly is no longer on a feeding tube. We can spoon-feed her. My sister Tess is dedicating her life to trying to maximise Polly's quality of life. And there's a great team in the care home.

We have a "do not attempt resuscitation" notice informed by her values and beliefs and she wouldn't be treated for life-threatening infections.

There isn't any hope that she will regain her ability to make her own choices. It's nine years on, it doesn't happen that way. It's not like in the movies. But of course we live with hope for a good death for her eventually, belatedly - we can hope for that.

A resource for families with relatives in vegetative and minimally conscious states is available here, external.

Photographs from www.welovepolly.org, external, reproduced with permission.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external.