Touring the Lake District with an 80-year-old guidebook

- Published

In 1939, the newly established Penguin Books published six guides to various English counties, complete with touring maps, aimed at the middle-class motorist. Emma Jane Kirby has been driving around the UK with those first-edition guides in her hand to see how Britain has changed since the start of World War Two. Next stop: the Lake District.

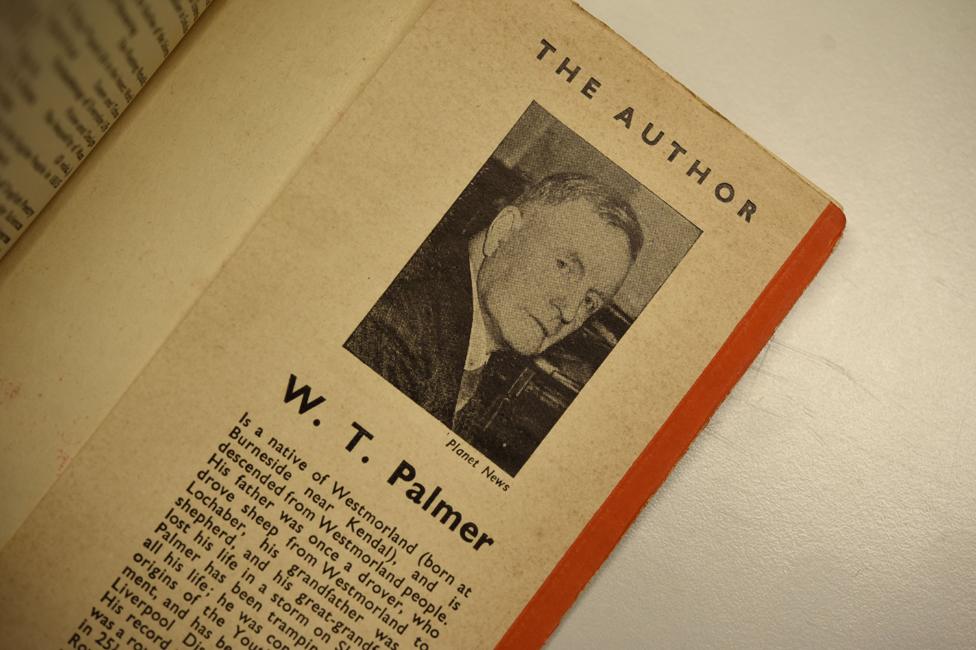

"No other countryside in the world," boasts my guide's author, W T Palmer, "can offer such variety, to suit all tastes and pockets."

It would be wrong of me to suggest I had developed a favourite county during my tour of England with the 1939 Penguin guides, but I think I can say that if I had the chance to go back in time to meet just one of the books' authors, I'm pretty sure I'd plump for W T Palmer.

Some of the other authors' waspish humour is certainly more amusing and their observations perhaps more perspicacious but what I like so much about Mr Palmer is that rather than showing off his knowledge or casting judgement on the peculiar eating or dancing habits of the locals, he just seems terribly concerned that everyone coming to the Lake District in 1939 should have a jolly nice holiday. Yes, everyone.

Even the less well-off.

"Youth hostels are established in our area for the benefit of youngsters who are compelled to take holidays on small means… the movement has been accused of bringing a newer and poorer type of guest and keeping away more profitable people. So far this cannot be proved."

Borrowdale Youth Hostel, noted W T Palmer with some excitement, was just about to open as he penned his guide. In fact the whole youth hostel movement, of which he was a fervent supporter, had only begun a few years previously.

As I drive warily over the Fisher-Price-sized stone bridge in my stocky 21st Century hire car, a small group of YHA guests clad in sturdy walking boots and serious-looking cagoules wave their Ordnance Survey maps at me as I pass. To the right of the original low-slung wooden building, a barefoot, blonde young man, his hair crusted into dreadlocks, pets a dog in front of some trendy pod-like wooden cabins.

"That was always the whole point of the hostel movement," grins YHA archivist Duncan Simpson as he ushers me into Borrowdale's bar and orders us coffee.

"At a shilling a night, it allowed everyone to get a holiday in the countryside and provided an opportunity for all classes and backgrounds to mix. You could be a bishop bunked next to a steel worker. And while there weren't those pods outside, you were allowed to bring your own tent."

He shows me the carpeted dormitories and the pristine shower blocks - most of the youth hostels in W T Palmer's day could boast only of the possibility of nearby "river bathing".

But basic comforts - or the lack of them - did not seem to mar his enthusiasm. In fact he devoted a whole chapter of his guide to hostelling.

Archivist Duncan Simpson tells the World at One that affordable holidays gave people more freedom.

A couple of people are clearing up the remnants of their late breakfast in the communal kitchen, and in the games room the barefoot young man and his friend are laughing over a last game of table tennis before heading to the hills.

"It's exactly like in 1939," says Duncan. "Everyone would be out walking during the day… and of course there was no bar to hang around in in 1939 - alcohol wasn't allowed."

But surprisingly, there were women. (Palmer chastely calls them "maidens".) By 1939 half of the guests in the Lake District hostels were female and I tell Duncan Simpson that Palmer writes obliquely that the Lake hostels hold a "high reputation for freedom, which attracts more and more visitors to the chain".

Duncan laughs and tells me that's why there was plenty of local - and national - opposition.

"Youth hostels were luring people into the countryside in mixed groups and away from church on Sundays," he tells me. "And they gave people not only the freedom to get out in the open, but also the freedom to meet the opposite sex without chaperones!" He shakes a finger at me.

"But there were rules," he insists. "To make sure people were well-behaved."

Find out more

Read Emma Jane Kirby's account of following the 1939 Penguin guides to Kent, Derbyshire and Cornwall

Listen to her report from the Lake District at 13:00 on Tuesday 3 April 2018 on BBC Radio 4's The World at One

Or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer

I'm not sure that W T Palmer was a true libertarian - every third page of his guide robustly reminds readers of the rules and regulations of the popular 1930s sports of fell walking and rock climbing, and the climber's responsibilities.

"Rock climbing has become an important, if select, sport in the Lake District… it must be impressed that the sport is both difficult and dangerous... any inexperienced person venturing on these forbidding slabs, sheer cracks and fangs of rock, invites disaster and mishap."

Mountaineering instructor Zac Poulton

As mountaineering instructor Zac Poulton and I start our ascent up Blencathra, the sky ruptures and spills a spiteful torrent of freezing rain and sleet on top of us.

"In '39, climbers were much hardier, really pushing themselves psychologically," says Zak amiably, over his shoulder, as I trail miserably behind him.

"They'd climb using any rope they could find, ropes that wouldn't have been tested… they'd steal mother's washing line… These days we climb with several hundred quids' worth of metal dangling from our harness so we can anchor ourselves to the rock."

A bullying wind comes to join the rain. Zak and I were meant to meet in kinder weather yesterday but he was delayed for five hours after coming across a woman who had slipped on snow and smashed into some boulders descending Helvellyn. He's amazed there were not more accidents in W T Palmer's day, especially as the 1930s climbers would have been climbing either in hobnailed boots or the new rubber-soled plimsolls that were coming over from Europe.

A dry stone wall at the foot of Blencathra

"They wouldn't have had all the waterproof kit we've got," says Zak nodding at my breathable coat. "It would have been tweed jacket, ex-Ministry of Defence smocks and woollen jumpers. If you wanted to climb in the Lakes, you were going to get wet and cold - it was the old British attitude; one must suffer for one's sport!"

Climbing, however, is clearly not my sport and so we turn around, ignoring W T Palmer's boast that he once "tramped" 85 miles in the Lake District in just 25 hours and 30 minutes.

As we trudge back down towards the car we chat about how Palmer seemed both fascinated by rock climbing but also rather fearful. Defrosting later in a Keswick cafe, I look at the back flyer of my Penguin guide and learn with a shiver that he lost his great-grandfather on Shap Fell during a storm.

I also learn that his father was a drover - and his strong affinity and respect for the fells and their farmers permeates the book. Penrith, says Palmer proudly, is an important and "distinguished" agricultural centre.

"You wanted quality, here she is now!' sing-songs the auctioneer at Penrith and District Farmers Market as a startled sheep surges into the pen, flashing the red mark on her fleece. "Seventy-five pounds I'm bid. Who'll give me £80?"

The elderly farmer beside me growls into his sausage sandwich.

"Sheep aren't as hard as they used to be," he says. "Back in the day, we never took them off the moor - now we bring them down into the lowlands and they've gone a lot softer."

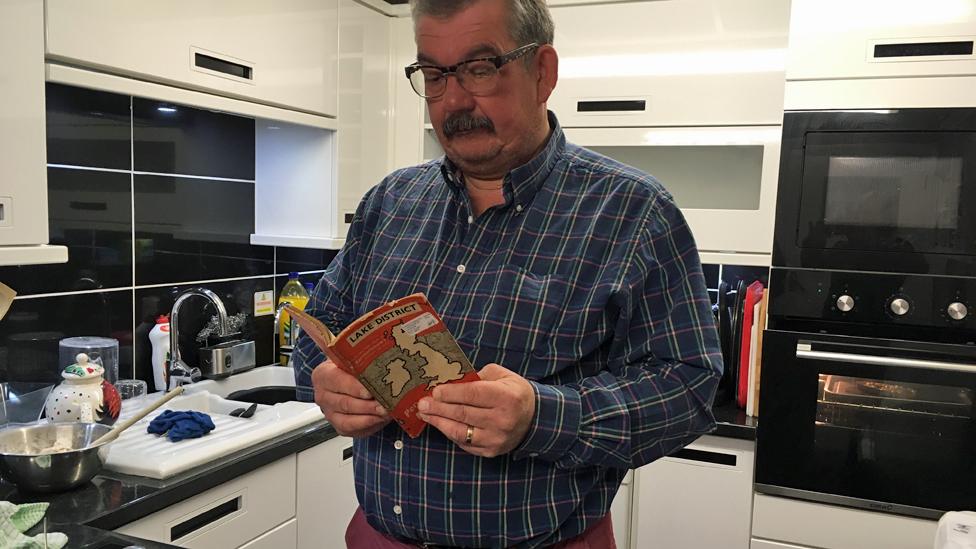

I show him the 1939 guide I'm using to tour his county and tell him that 80 years ago its author assured readers that most shepherds and farmers went about "their daily work in the saddle".

"I've got petrol in my horse today," he quips. "It's called a quad bike." He wipes some tomato ketchup from his chin on to his sleeve.

"Other than that," he says after a moment's reflection, "it's still the same."

Herdwick sheep on Wansfell

A younger farmer, here to sell last year's lambs, disagrees.

"It's all about quantity and low price today. I'm 33 but I'd rather have lived in my granddad's time in farming rather than face what's coming now, definitely."

The sheep in the holding pen start bleating, perhaps sensing that whatever price they command this morning, the day isn't going to end well for them.

"Has it improved in 80 years?" asks a fell farmer rhetorically. "No. Because then there'd be a lot of people working on a farm together." He takes off his tweed deerstalker hat and wipes his forehead. "Now it's a lonely job, believe me."

I daren't mention the local celebrity shepherd, James Rebanks, and the 107,000 followers of his Twitter account, the Herdwick Shepherd - but I feel quite sure that W T Palmer would be delighted that his beloved sheep were big on social media.

Grasmere gingerbread - did saleswomen wear Victorian costume in 1939?

Comfort is easy to come by in Cumbria. The county's sweet tooth is so notorious that local shops sell "bags for life" bearing the logo, The Cake District.

"There are many dishes peculiar to Lakeland which should be enjoyed… Kendal mint cakes, Grasmere gingerbread, Hawkshead wigs are worth trying," writes our guide.

"I am the only person now with the original recipe for Hawkshead Wigs," says chef Mark Whitehead, tipping caraway seeds into a bowl.

He shrugs.

"I'm afraid your guide would be hard pushed to find a wig in Cumbria nowadays - the only bakery in Hawkshead shut down years ago."

"You'd be hard pushed to find a wig in Cumbria nowadays," says chef Mark Whitehead

Thought originally to be an offering to the Norse god Wigga, wigs are a sort of rich bread spiced with caraway seeds, and made not with water but with milk and butter.

Until a few years ago Mark used to get up at 5am every morning to bake wigs for customers of a cafe he ran, serving them with local cheese and his own Hawkshead Relish or Cumberland sausage. Not any more.

"The problem is, that having all that butter and milk in them they go stale quickly," he explains kneading the sticky dough. "Plus they also take four hours to make - who's got time for that these days?"

Bowness, departure point of steamers

W T Palmer encouraged his readers to take a three-hour tour on one of Windermere Lake's steamers. Starved of time, local historian Roger Bingham and I have opted for the 45-minute island spin from Bowness. Over the loudspeaker our tour guide is giving a running commentary in a thick foreign accent. Roger motions towards the quayside where scores of Japanese tourists are pouring off coaches.

"Even though the war was coming, in 1939, this place would have had huge crowds on the promenade in their Sunday best," he says. "The workers would come in charabancs from Lancashire… but Westmorland in 1934 had more cars than anywhere else on Earth!"

We chat about how Palmer, perhaps in his bid to give everyone one last nice holiday, steadfastly omitted to make any mention of the war that everyone knew was coming; by spring 1939, the Westmorland Gazette was full of news about blackout practices and air-raid precautions.

The accented voice over the loudspeaker interrupts to inform us we are nearing Beatrix Potter's house. There's a crackling of waterproofs as tourists rush to pull cameras and phones from their pockets.

"I'm afraid, in the 1930s, the locals saw her as a la-dee-dah off-comer who dressed as a tramp," says Roger Bingham. "And she wasn't nice to children. Whether she had a pet rabbit and was nice to Peter, I don't know."

The two ladies beside us who have been surreptitiously ear-wigging our conversation look crushed.

Beatrix Potter "wasn't nice to children", says historian Roger Bingham

"Still," adds Roger thoughtfully, "she was buying up a lot of Lakeland farms in the 1930s to give to the National Trust - she did a lot of good here."

Perhaps W T Palmer just wasn't much of a bunny man but he doesn't mention the Potter canon at all in his guide. He is however extraordinarily proud of another local writer - Hugh Walpole.

"Lakeland is full of literary homes and haunts… in the new time Sir Hugh Walpole has settled in the country and many of his best novels deal with the Herries and other Lakeland families and landmarks."

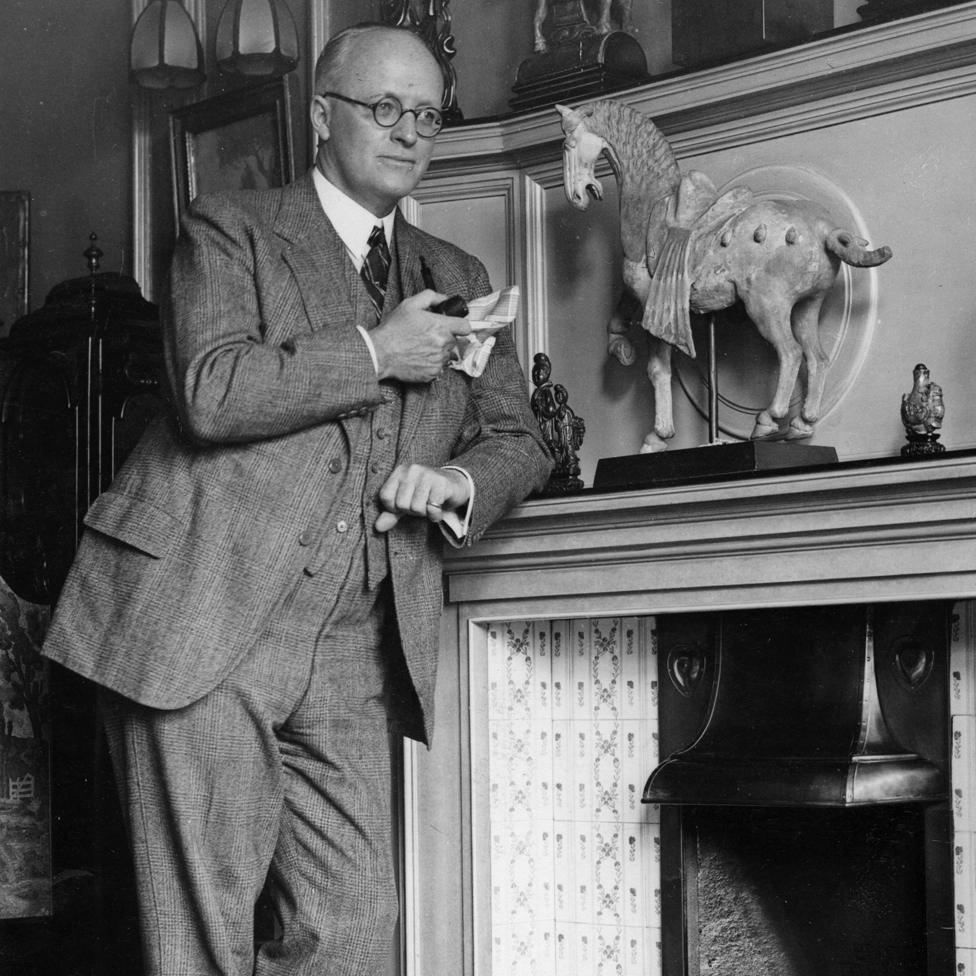

Sir Hugh Walpole - in the 1930s he was writing a novel a year

Eric Robson, chairman of Radio 4's Gardeners' Question Time and a huge fan of Walpole's, shrugs his shoulders as we study the noble-looking bust of the author in Keswick's museum.

"How he fitted in here, is a mystery," he muses. "Cumbrians are a blunt crew - and here was a gay, spendthrift intellectual… but he caught the essence of this place and its people and he knew his cast. Cumbrian people recognised he was their voice on the world stage."

We peer at two handwritten manuscripts displayed in a glass case. The writing is distinctly scruffy and childish.

"He also couldn't spell and had no grasp of grammar!" laughs Eric.

If you're of a literary bent and yet are scratching your head over the name Hugh Walpole, don't be too hard on yourself. In the 1930s, when Walpole was writing a novel a year (he produced 50 in his lifetime), he was selling 20,000 copies of each novel in hardback within the first two weeks of publication. John Buchan reviewed his Lakeland trilogy, saying the work was the best English novel since Thomas Hardy's Jude The Obscure.

But he's been out of print for years and it's difficult to find a copy of his novels even in second-hand bookshops. So what on Earth happened to crush this literary Lakeland giant who in the late thirties was touring America and pulling bigger audiences than Dickens had, 80 years earlier?

"The war!" smiles Robson. "The war brought in a new generation of writers who wanted to break down the mould of literature as we knew it and Walpole was a representative of the old hierarchy they wanted to tear down."

On the end page of W T Palmer's 1939 book, there's an illustration of two exhausted but very contented little penguins, reposing on their haversacks.

Six months after the publication of his meticulous guide, Britain and France declared war with Germany and the entire Penguin County Guides series with their detailed maps - which would have been a gift for foreign agents - were pulled from the shelves. Special Forces requisitioned Borrowdale Youth Hostel; Hugh Walpole and Beatrix Potter would be dead within 18 months; the holidays were well and truly over.

I sit in the fading light in Hawkshead graveyard and listen to the church bells chime.

"Return to your lodgings," advises W T Palmer gently. "You have had a full day."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external