How to disagree well: Two close friends who have reason to hate each other

- Published

Fiona Gallagher and Lee Lavis have good reason to hate each other - but have become close enough to regard each other as brother and sister. It's a friendship which they believe has much to teach others, writes the BBC's Hugh Levinson.

Fiona

Fiona Gallagher was born in 1968 to a Catholic family in Derry who were firm nationalists. She grew up with what became known as The Troubles.

"My memories are literally cluttered with recollections of foot patrols, house raids. Our house was raided over a period of 13 years. And it would have been maybe every other month, every two months. But it was constant. These men, came into my bedroom, at 4am, 5am, shouted me out of my bed. That's chaos, roaring, muddle. Those are my earliest memories and they are all terror."

It was a close family - and Fiona felt particular affection for her oldest brother Jim. "He was very giggly, you know, he would have had a great sense of humour. He was a very tall, beautiful, solid fellow, very gentle-natured. And he just adored his family and especially me."

At the age of 16 in January 1972, Jim by chance witnessed the events of Bloody Sunday - when British soldiers shot 28 unarmed civilians during a protest. Fourteen died. Jim was radicalised by what he had seen and joined the IRA. "That was his mission then, to defend his people," Fiona remembers.

Soon after, Jim was arrested, convicted of being an IRA member and sent to jail for four years. Just six days after his release, a soldier shot him dead. For Fiona, this cemented her revulsion of the British military.

"I remember their uniform. I remember their visors on their helmets. I remember their guns. And I hated them. I totally dehumanised them. To me they were just uniform. They'd no face because they were faceless to me."

Lee

Lee Lavis was brought up in a small village near Burton-on-Trent. He left school at the age of 16 with no qualifications. He found work as an apprentice butcher but wanted a change. "Frozen ox liver at six o'clock in the morning isn't much fun," he says.

In 1988 he decided to join the army "because I was 18 and I was full of teenage hubris and this kind of mythological view of war - medals, bravery, being met on the quayside by a grateful nation". He did two tours of duty in Northern Ireland at the tail end of the troubles, in strongly nationalist areas including South Armagh. He had a clear and fixed opinion about the local civilians.

"Part of military training is your enemy is dehumanised," he says. "Because the IRA was almost exclusively drawn from the Nationalist community, it wasn't long before [I viewed] that whole community over there as in the IRA. I even used to view the kids as tomorrow's IRA. So in that sense, I kind of viewed the whole nationalist community as guilty."

Lee's attitudes started to change during his second tour of duty. He began to read about Irish history and culture. The big change happened when he was invited to go away for a weekend with members of a disabled youth club from Newry.

"In that kind of circumstance, where we stay for a weekend watching this football match, they became human to me. Suddenly I found out what it was like to be on the other side - the fear of just going to do your shopping. There might be an army patrol and someone might fire."

Meanwhile, becoming a mother gave Fiona pause for thought. "That's when I started questioning myself. It is up to me if I pass everything on to the next generation."

Five years ago, she was on Facebook and clicked on a video made by a former soldier on the Veterans for Peace page. "I was expecting to hear the same rhetoric - to big up the British Army and the wars, but I could see he wasn't saying that, he was saying the opposite. I got very emotional."

Fiona wrote an impassioned post in response. "I just spilled everything out and held nothing back."

Meanwhile Lee had had his own transformation. He had survived many challenges including addiction and homelessness and restarted his education. With a postgraduate degree in conflict resolution under his belt, he came across Fiona's post on the website. "I remember reading it and just had this urge - I would like to meet this woman," he says.

After emails and texts back and forth, they agreed to meet in person in a bar.

"I'm walking towards the door to go in," recalls Fiona, "and everything is slowing down for me. What I imagined I was going to meet in there was a soldier with a gun. It took me right back to my childhood. But I just thought: 'Come on, put one foot in front of the other.'"

Lee was just as nervous. "I suppose I had this sort of uncertainty. I had this image of someone who was going to walk in with an Easter lily and a Tiocfaidh ár lá [Our Day Will Come] badge."

Fiona was first take the initiative. "I thought, 'What do I do next?' I'm a hugger and Lee definitely was not a hugger at the time. I just went over and nearly threw myself on him and hugged him."

The pair quickly became friends, with a relationship based around everyday conversations about family life and shared passions.

"Now we've transcended speaking about the conflict. We'd be more apt to speak about music," says Lee. "We went to see Morrissey together because we're both big Smiths fans. That's prior to me burning all my Morrissey CDs, given some of his recent statements."

They both speak warmly of each other. "That man is a massive part of my life. He's such a lovely soul," says Fiona.

"I would view Fiona as a sister, someone I love to death," says Lee.

How to disagree better - eight tips

You don't have to agree - disagreeing itself isn't the problem, it's how we do it

Don't aim for the middle ground - splitting the difference isn't the answer when you fundamentally disagree

How you talk is more important than what you talk about - "What matters is the dynamic that exists between us," says couples counsellor Esther Perel

Speak truthfully - to form meaningful relationships what's needed is total honesty

Listen intently and aim for empathy - it's all about "a willingness to take in what the other person says," says Esther Perel

Dial down the rhetoric and rein in the insults - "No one in history has ever been insulted into agreement," says Harvard professor Arthur Brooks

Understand the difference between fact and opinion - opinions are perspectives to be tested against the evidence, not just weapons to be wielded against our opponents

Go looking for conflict - Then "listen compassionately, give your point of view and express love," says Arthur Brooks

Douglas Alexander presents A Guide to Disagreeing Better on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 on New Year's Eve - it is available now as a Seriously podcast

How did they do it?

They are clear that their friendship is not based on them always seeing eye to eye.

"Do we agree about a united Ireland?" asks Lee. "That's something Fiona and I would not agree on. I'm not a Republican. I'm an Englishman in Belfast. So for economic reasons I'd vote for continued union."

Fiona can cope with that. "Wouldn't the world be really boring if we all agreed with each other?" she says.

To become this close - and this relaxed about differences of outlook - what was required, they both say, was total honesty.

Fiona's brother, Jim. who was shot by a soldier

For instance, Lee recalls a tactic he used when on infantry foot patrol. "My instinct was to look for children from the nationalist community and get among them. No sniper would fire if I'm surrounded by children. At the time I didn't think about the fact I was using children as human shields."

He has been frank about this when talking to Fiona. "I never tried to dress that up. I never tried to downplay my attitude to her community when I was in the army."

Fiona says many people find this level of honesty too frightening - and urges them to overcome the fear.

"No matter what you do, no matter how you try to move forward and disagree better, or listen and understand, there's always going to be somebody that's going to bring you down about it, ridicule me or be negative about it. Let the negativity go. Don't be afraid."

Douglas Alexander presents A Guide to Disagreeing Better on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 on New Year's Eve - it is available now as a Seriously podcast

You may also be interested in:

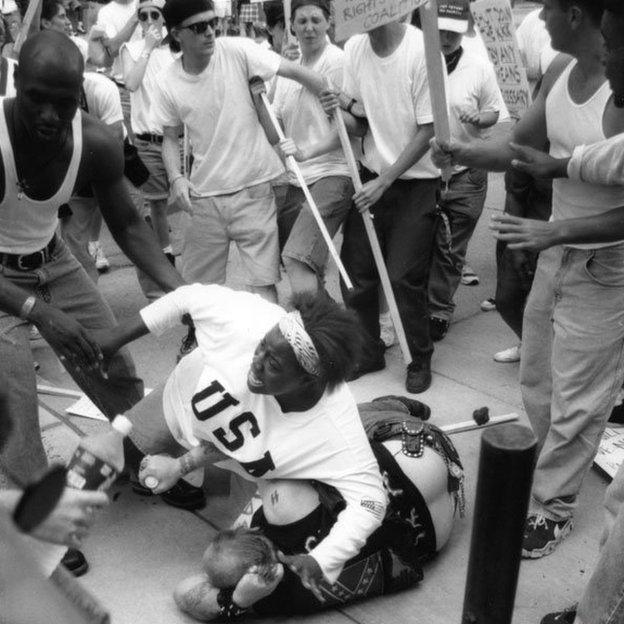

In 1996, a black teenager protected a white man from an angry mob who thought he supported the racist Ku Klux Klan. It was an act of extraordinary courage and kindness - and is still inspiring people today.