What would you say to the men who killed your mum?

- Published

What would you say to men who killed your mother? And could you forgive them? These were questions that faced 17-year-old Sarah Salsabila on an Indonesian prison island one day last October.

Iwan Setiawan was on his motorbike, speeding past the Australian embassy in Jakarta. His mind was on his wife, whose arms were around his chest and whose pregnant belly he could feel pressing against his back. Their second child was due within weeks and they were on their way to hospital for a check-up.

"Suddenly there was this incredibly loud sound and we were thrown into the air," he remembers.

Iwan didn't know till much later that it was a suicide bomb, the work of a local Islamist militant group, Jemaah Islamiyah, a militant group with links to al-Qaeda responsible for a series of attacks in Indonesia, including the Bali bombing in 2002 that killed 202 people from around the world.

"I just saw blood. Lots of blood. Metal went flying into one of my eyes, destroying it."

His wife was thrown from the bike, landing metres away. Both were rushed to hospital and, in a state of shock, a badly injured Halila Seroja Daulay went into labour.

"She was rushed into the operating room after getting contractions. But praise be to Allah, somehow she was still able to give birth naturally," Iwan says.

That night Rizqy was born. His name means "blessing".

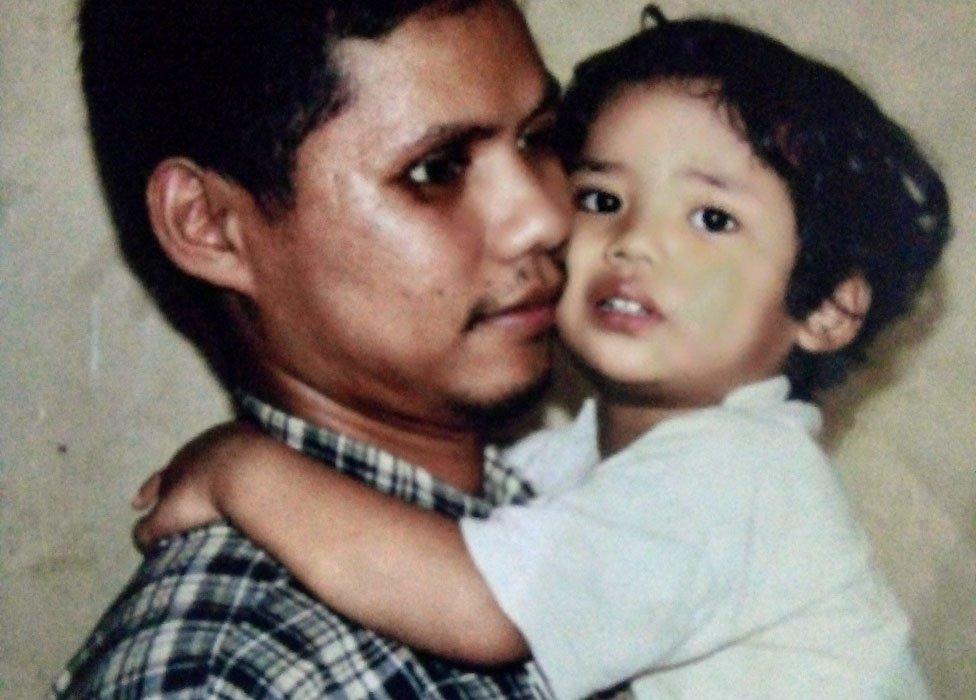

Iwan and Rizqy

"My mum was so incredibly strong," says Iwan and Halila's first child, Sarah, tearfully. "Even though her bones were broken she was able to give birth naturally to my brother. She was so incredibly strong, my mum."

But Halila never recovered from her injuries and two years later, on Sarah's fifth birthday, she died.

"I lost my best friend, my soul mate, the person who completed me. It's so painful to talk about it," Iwan says, also through tears.

Sarah and her mum, Halila

At first, he was filled with a desire for revenge.

"I wanted the surviving bombers to die, but I didn't want them to die quickly," he says.

"I wanted them to be tortured first. I wanted their skin to be cut and salt put in the wounds so that they had some idea of the pain their bombing caused, both physically and mentally. My children and I have struggled so incredibly hard just to keep living."

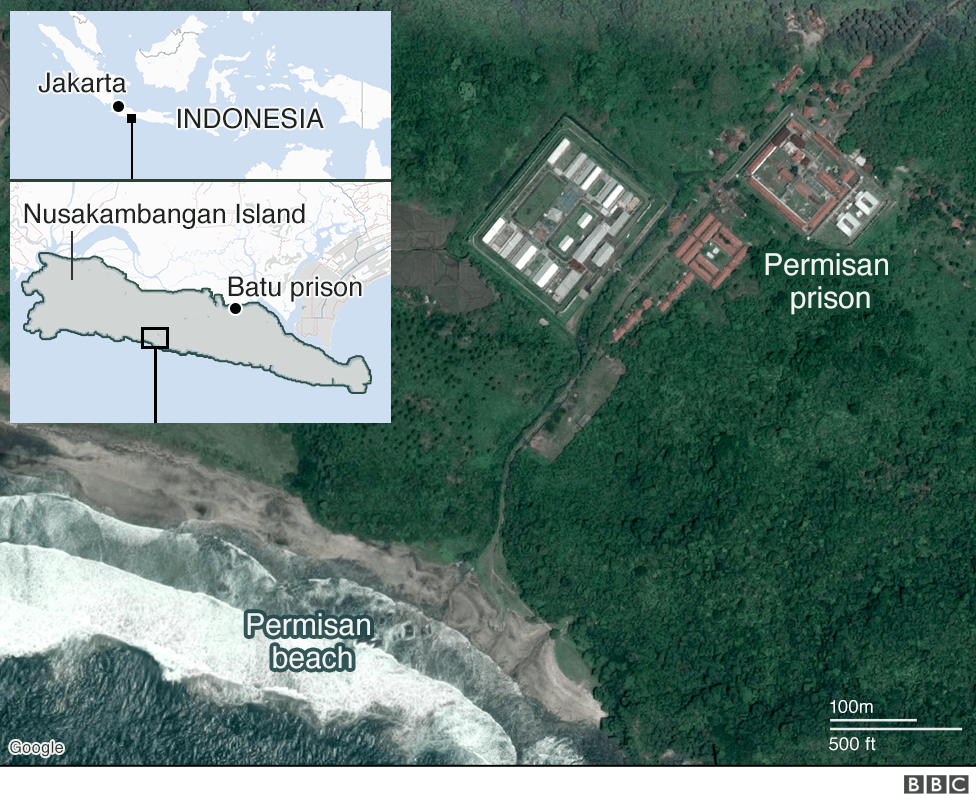

It's October 2019, 15 years since the 2004 Australian embassy bombing and 13 since Halila's death. Rizqy is now at junior high school while Sarah's school days are almost over. Together with Iwan we're on a boat crossing a narrow strait to the jungle-covered island of Nusakambangan, off the coast of Java, the site of Indonesia's highest-security jail.

Sarah wants to know why the men did it

We are going to meet two men on death row. Both were found guilty of carrying out the bombing that left the children without a mother and Iwan without a wife.

"My heart is racing, I am feeling very emotional. I don't have the words to explain what's going on in my mind," Iwan tells me as we stand at the port, in light misty rain.

"I just hope this journey will open up the hearts of the bombers."

Iwan has met one of the men before, thanks to Indonesia's unique deradicalisation programme, which arranges meetings between militants and their victims. But for his children it's the first time. I ask Iwan, for what feels like the 100th time, if he really wants to do this.

Crossing divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

"Yes, it's very important for my children to have the opportunity," he says firmly.

"I always taught them not to be angry. But they want to know what the men are like who did this. We want to have this chance to meet them."

It's clear they're a very close family.

Sarah, 17, is dressed stylishly in a black headscarf, striped shirt and long trousers. She takes selfies throughout our journey and, like many teenagers, is glued to her phone.

But when she talks about why she is doing this, her eyes fill with determination.

"I hope this meeting will make the terrorists think, and that they beg for forgiveness from Allah. If they truly regret what they did, then it can influence others and hopefully it will never happen again."

Sarah has a burning question, one she has waited years to ask.

"Why did they do it? That's what I want to know."

Dressed in an orange jumpsuit, Iwan Darmawan Munto, alias Rois, sits waiting in a small meeting room. He looks frail and is in a wheelchair - he has had a stroke recently but his legs and hands are still handcuffed.

Iwan Darmawan Munto, alias Rois, is kept in isolation in Batu prison

At his trial, Rois stood and waved his fist after the guilty verdict was announced, declaiming, "I am thankful for being sentenced to death… because I will die a martyr!" It's assumed the Australian embassy was targeted because of its alliance with the US in the war in Iraq.

Two armed prison guards in balaclavas stand either side of him. The air is very tense. They tell us that if Rois tries anything we must move quickly to the walls.

Iwan, Sarah and Rizqy greet him and sit down on plastic chairs. It's Iwan who breaks the silence.

"My children are curious to meet the person who caused them to lose their mother and their father to lose his eye," he says.

Rois asks casually where Iwan was when the bombing happened.

Sarah and Rizqy meet Rois

Iwan explains that his wife was pregnant and that she gave birth on the night of the bombing. "This is the child she gave birth to," Iwan tells him, pointing at Rizqy, who stares at his hands.

Rois responds, "I have a child, too. I haven't seen my wife or child for years. I really miss them. I am even worse off than you. You're still with your children. My child doesn't even know me."

Rois looks at Sarah and Rizqy who are both now intently staring at their hands, avoiding any eye contact.

Suddenly everyone is looking at Sarah. We know that she wanted to ask something.

It's too much for her and she breaks down. Iwan rushes over to her and holds her head in his hands - embracing her protectively. She then manages to ask Rois quietly why he did it.

At his trial, Rois said he was looking forward to a martyr's death

"I didn't do what they said I did. Why did I admit to it? The answer comes by looking at my eye," he says, pointing at his cloudy eye.

"Maybe when you are older you will understand," he goes on. "I don't agree with attacks where the victims are Muslims. That's not right. You cannot kill Muslims - just to hurt a Muslim, it's not right."

I jump in, "What if the victims aren't Muslim?"

"I don't agree with that either," he says quickly.

Rois is now in an isolated cell in this maximum-security prison, as guards say they are worried about his influence over other inmates.

He previously shared a cell with radical preacher Aman Abdurrahman, who pledged allegiance to the so-called Islamic state from behind bars. Both are suspected of having planned a 2016 bombing in Jakarta from inside prison.

Before Iwan leaves, Rois does offer to pray for him. "All humans have made mistakes. If I have wronged you in any way I apologise. I feel pain. I really do," he says.

But outside, Iwan seems deeply shaken.

"He still thinks he did the right thing. I fear that if he had the chance he would do it again," he says, holding back tears.

"I'm really disappointed. He has caused so much pain but he doesn't want to admit it. What more can I do?"

We pile back into the military bus that is taking us around the prison island, at one point passing a group of monkeys swinging through the trees near the road.

There are two prisons on the island and we are going from one, Batu, to the other, Permisan, to meet Ahmad Hassan - the second man on death row for his role in the attack that killed Sarah and Rizqy's mother.

Hassan on trial

In shots taken during his trial Hassan is seen raising his fist in defiance and staring angrily at the camera as he leaves the court, surrounded by security guards and hordes of journalists, but it's a very different man we meet today.

Dressed in a long Islamic robe with a prayer hat on, he looks nervous and speaks softly.

Iwan has been to the jail to meet him once before.

"I have invited my children to meet you," Iwan tells him, placing a hand gently on his knee. "I want them to understand too why you did the bombing that killed their mother and caused me to lose one of my eyes."

Hassan nods solemnly.

"They have to know. They lost their mother so young," he says.

"I have told your father and I now have the opportunity to tell you, praise be to Allah, I have this chance.

"I never wanted to hurt your father, he just happened to be passing by, and my friend who was carrying the bomb blew it up at that time. I hope that you, the children of Iwan, can forgive me."

His voice starts to break. "I am a flawed human. I have made many mistakes."

Find out more

Facing the bombers is on the BBC News Channel on Saturday and Sunday 22/23 February at 21:30 GMT and and at various times across the weekend on BBC World News

You can also listen to Rebecca Henschke's two-part documentary for Heart and Soul on the BBC World Service

Sarah stares at him, but says politely and firmly. "Why did you do something like that? What was the reason?"

"My friends and I were given the wrong education and learning. I wish that we hadn't acted before we had really gained knowledge and understood what we were doing," he replies.

Sarah then tells him her story. How her mother died on her fifth birthday, how they had been planning to have a party at four o'clock, and how joy had turned to despair.

"I would always ask my dad when I was little, 'Where is my mum?' and he told me she was at Allah's house. I asked where that was, and he said it was the mosque.

"So I ran away to the mosque. My grandmother was looking for me, and when she found me I told her that I was waiting for my mum. I was waiting for my mum to come home. But she has never come home."

Hassan prays for forgiveness

Hassan closes his eyes and opens his hands in prayer. Over and over he mumbles a prayer seeking forgiveness from Allah.

"Allah wanted me to have to meet you and be forced to try and explain," he finally manages to say.

"But I can't explain to you my child, I am sorry.

"I can't hold back my tears. I take Sarah as my own child. Please, please forgive me. It's in your hands."

Everyone in this tiny room is crying.

Iwan says later how much these tears from Hassan meant to him.

"When I saw Hassan crying - that's when I knew he was a good person. He can feel the suffering and pain of others. Maybe at that time he was influenced by the wrong people with the wrong ideas, and now he has opened his heart."

At the end of the meeting they take photos together. They hold hands. It's amazing to feel the level of forgiveness in this room.

"I would always say that the death penalty wasn't good enough for them, that they should be tortured first to feel the pain we suffered," Iwan says. "But Allah favours those of his followers who can forgive."

We head out of the room, wiping tears from our faces and get back on the military bus.

There is a famous beach on this island, behind the prisons - a place inmates never see. It's called Permisan beach, or the white beach, and is where the country's special forces train.

Sarah, Rizqy and Iwan ask to see it.

It's a wild place with jagged rocks, the surf pounding the shore. Holding hands, Sarah, Rizqy and Iwan run across the sand. I haven't seen Sarah smiling like this before.

"The meetings today have taught me so much," she tells me.

"Hassan said sorry and he regrets what he did. I have learnt that someone can do something so terrible but then they can change, and I forgive him.

"I am smiling lots now because what I have wanted to know, and what I have wanted to ask for so long has been asked and answered.

"I feel waves and waves of relief."

A hug of forgiveness

Garil Arnandha's father was one of 202 people killed in the 2002 Bali bombings. Here he meets bomber Ali Imron, who apologises and asks for forgiveness.

Garil Arnandha, whose father died in the Bali bombings in 2002, met Ali Imron who is serving a life sentence for the attack