World suicide prevention day: 'Could I have stopped my dad killing himself?'

- Published

We think we know what suicidal behaviour looks like when someone is young, but when they are elderly the signs are often quite different. Kris Griffiths never imagined his father would kill himself, but now realises he missed a number of red flags.

If you stop someone in the street and ask what the words "male suicide" brings to mind they'll probably mention a singer, maybe Kurt Cobain or Keith Flint, or perhaps a footballer, such as Gary Speed. Most likely it will be someone who became famous when they were young, perhaps lived a life of excess, and didn't make it to the relative stability and equanimity of middle age.

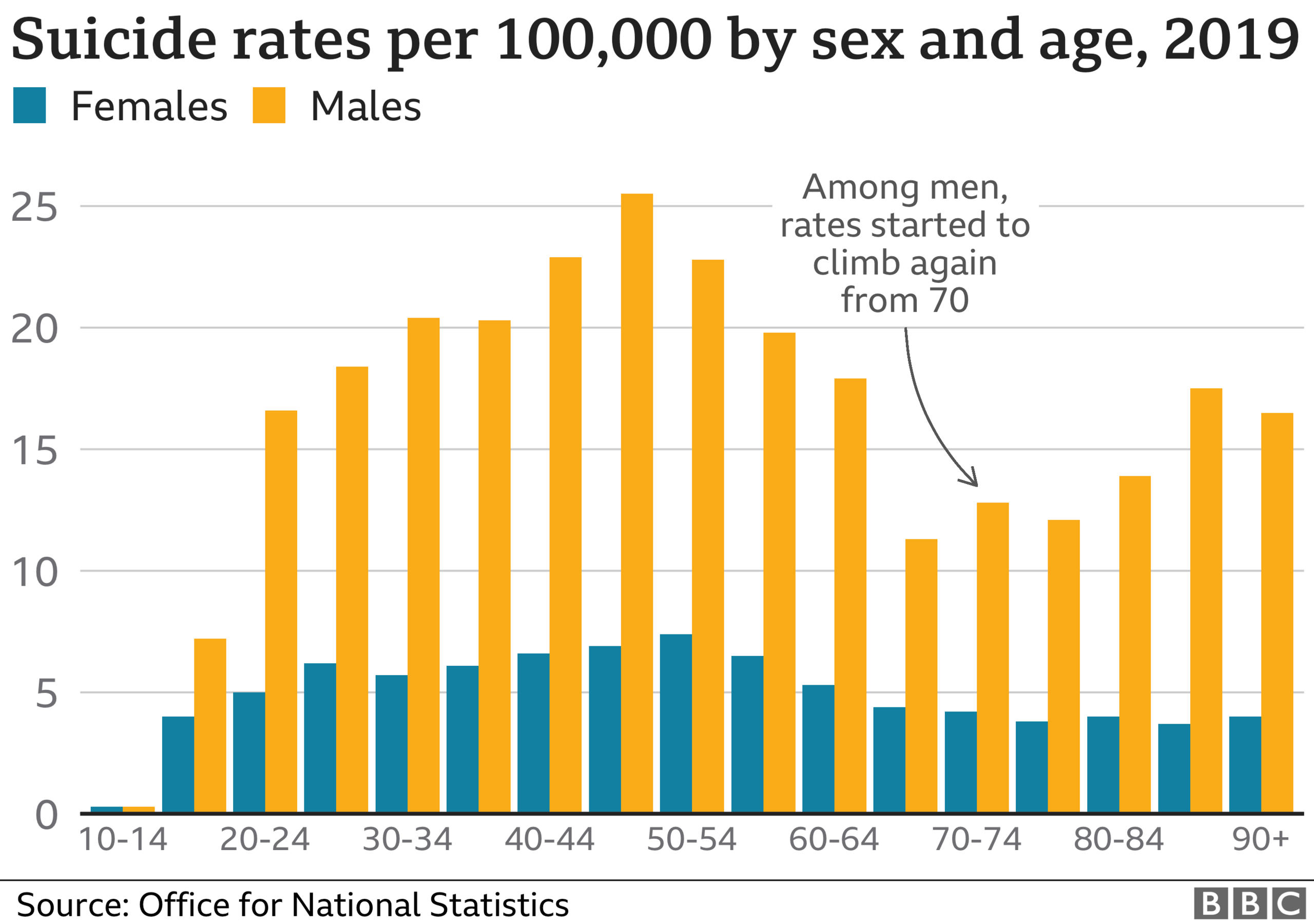

This perception is supported to an extent by statistics: suicide is Britain's biggest killer of males under 50, external, with 45 to 49 the peak age bracket, according to the most recent official figures for England and Wales, external. The figures also bleakly confirm that the overall suicide rate has risen sharply to its highest level since 2000, with 75% being men - one dies roughly every two hours.

Within these grim numbers, however, lies a hidden demographic of men who are extinguishing their lives far away from TV screens and Twitter feeds - a later age group where suicide rates rise again, but out of the public eye. In 2018 my father became one of them.

Dad was 76 when he took his life, 18 months after Mum had died following a long illness. He was never able to come to terms with the loss of his life partner, feeling increasingly lonely, useless and isolated, despite regular visits from his children and grandchildren.

One reason why three times more men than women kill themselves, is widely thought to be the lifelong conditioned adherence to masculine behaviour patterns: repressing emotions instead of expressing them, which is deemed weakness; and refusing to seek help, either from friends and family or health professionals.

The urge to self-medicate with drugs or alcohol is also far more common among men, which invariably compounds the problem, leading to impulsive behaviour.

What frequently separates the younger and older demographics, though, are the causes of the anxiety and depression that lead to suicidal ideas. In younger males these can range from identity issues to financial difficulties, often caused by loss of employment, and the perceived pressure to be economically successful.

These are less likely to be problems experienced by the 70-plus age group. For them, loneliness tends to be a key factor.

"The potentially harmful effects of loneliness and isolation on health and longevity, especially among older adults, are well-established," wellness author Jane Brody has written.

"Research has found that loneliness can impair health by raising levels of stress hormones, which in turn can increase the risk of heart disease, dementia and even suicide attempts."

In my father's case, the loss of his 45-year marriage partner, whom he had cared for devotedly in her final years, left him struggling. His retirement had not brought the contentment it had promised, and no number of visits from his children could dispel his loneliness. He had little in the way of a social circle - another factor that differentiates older men from women, who tend to be better socially connected.

Not long after Mum's funeral, Dad was diagnosed with cancer, which he typically kept as quiet as possible, stoically undergoing his radiotherapy until given the all-clear seven months later.

Even then there was no feeling of celebration or rejuvenation, no more joy to derive from things he'd once loved. Attendance at long-planned family engagements like Christmas was cancelled at the last second. He started to feel physical pains for which medics could find no cause.

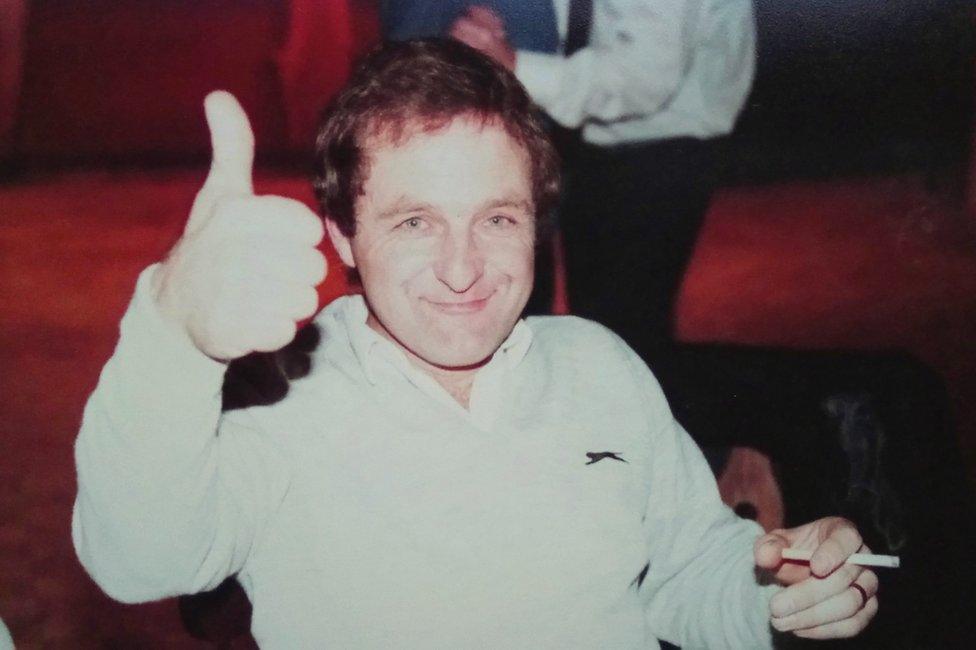

As a younger man, Dad's enjoyment of life had been infectious. A proud working-class man, who began and ended his working life as a bus driver, he enjoyed a beer and a smoke, and was always the life and soul of a party. He was ever the raconteur, and had a perpetual silly streak that didn't fade with age.

Anthony Griffiths: 1942-2018

His comedy idol was Norman Wisdom - he would never not find his films hysterically funny - yet he was also deeply moved by music, his favourite artists being Elvis and Roy Orbison, in particular their rousing balladry. When Orbison's Black and White Night came out on video he would watch it every weekend literally for months on end, as his downtime treat.

He was all about the simple pleasures, from an afternoon nap to a Slurpee on a hot day. He once broke an incisor chomping into a frozen Mars bar that had been in the fridge too long. But his biggest mortification was probably the time he found an exotic-looking French lager on bulk sale in a Calais supermarket and duly loaded up the car boot with several crates, only to find when cracking one open back in England that it was a sickly sweet shandy with a minuscule alcohol content. I'll never forget his swearing at the moment of realisation, before the hilarity of the error took hold. It must have taken at least a year to get through them all. He pretended to have "grown fond" of them at one point, but wasn't fooling anyone.

It's not just the causes of suicidal feelings that differ in older people, but also the symptoms.

"Older adults 'cry for help' in markedly different ways than teens, because depression looks different when we age," says Dr Patrick Arbore, who founded Friendship Line in the US, specifically to counsel elderly people at risk of suicide.

"Depressed older adults are more likely to be irritable than sad, and to complain about physical ailments their doctor can't find a reason for."

He discovered that older adults weren't calling crisis lines because they didn't see themselves as being in crisis. They were lonely and depressed, but it was a chronic, undiagnosed condition that developed over time.

While Dad was never officially diagnosed with depression, my siblings and I, fully aware of his isolation and anxieties, convinced him to move from his rural home to a wardened retirement property closer to us all. While he agreed to this at first, saying he'd do whatever we thought best, he later became hesitant and obstructive when it came to viewing properties, and non-committal on whether he wanted to move at all.

The interpersonal theory of suicide articulated by psychologist Dr Thomas Joiner, whose own father killed himself, proposes that there are two chief causes of suicidal desire, "thwarted belongingness" and "perceived burdensomeness" - with the simultaneous presence of both being particularly dangerous.

Only now does this make perfect sense, looking back at Dad's final predicament. He wanted to end the loneliness but not encumber his kids - or anyone, including himself - with the upheaval of moving.

"When young people talk about suicide or say 'I want to die', older adults are more likely to say 'There's no place for me' or 'I don't want to be a burden'," says Patrick Arbore. "While we're thankfully more sensitive to the effects of outside pressures on young people, such as bullying and online harassment, we miss clear warning signs with older adults."

Again, it was only when I later came across a checklist of red flags, external that I realised how many had been glaringly obvious, but tragically went unnoticed at the time. The obsession with getting his affairs in order - accepting literally the first offer on his house, while still not fully committing to finding a new one. Random gifts - insisting on getting my car MOT'd and fully serviced. The morbid talk of wishing he lived in America where he could easily obtain a gun - which I reflexively shut down ("Don't be stupid!") instead of engaging him on it. As I later read, discussing suicide is in no way advocating it.

How to get help

If you or someone you know is emotionally distressed, BBC Action Line lists sources of advice and support

Samaritans has a list of warning signs (for all age groups), external

The most poignant forewarning was the last. One afternoon Dad turned up at my house, 70 miles away, just to "hang out" for an hour, something he'd never done before. Gratified by this unexpected social effort I gladly chatted with him over coffee, suggesting we all go away for a family holiday once he'd sold up, and then after a hug he was gone again. It was the last time I saw him, as a couple of weeks later he was gone for good. I know now that he was saying goodbye.

My feelings of guilt started early because I had been able to see first-hand how lonely he was, rattling around his home with little to do except watch daytime TV. As a childless freelancer, I could spend weeks with him at a time, working from his house and a local library. When it was time to return home he would sometimes ask if I could stay one more day, which I couldn't always agree to. So I would feel guilty and despondent on those long drives back. Then, during one of my final visits, he asked if I would consider moving back in with him full-time, which I had to decline as it just wouldn't have worked out for me, a man in my late 30s, to be cohabiting with his father again in a rural dwelling. I can't help but look back on it all with profound sadness, knowing what was to come next.

"Risk states are dynamic - they wax and wane over short periods of time," says geriatric psychiatrist Dr Yeates Conwell of the University of Rochester in New York, who calls the suicidal state a "teeter-totter".

"There's a will to live and a will to die, and it goes back and forth."

If this oscillating motivation is allowed to swing unchecked, older men are far more lethal in their suicidal behaviour, Conwell says, citing studies that suggest one in four senior citizens who attempt suicide dies, versus one in 200 for younger adults. They plan more carefully and use deadlier methods, while physical frailty reduces the likelihood of recovery from injuries, and increased isolation diminishes the chances of rescue.

"Older age is significantly associated with more determined and planful self-destructive acts," says Conwell. "And fewer warnings of suicidal intent."

This makes intervention to diagnose and treat depression all the more important, and it works. A 2009 US trial found that anti-depressant treatment significantly reduced the risk of suicidal ideation for those aged 65-plus.

A rapid rise in the older adult population, driven by the ageing of the baby boomer generation, means elderly suicide numbers are likely to continue rising.

It's telling that My Generation by The Who became something of an anthem for the boomer cohort, with its central "Hope I die before I get old" line.

Only now do I wish that lyric had never been written.

You may also be interested in:

Suicide in Northern Ireland: 'I have no sons left'