The science of addiction: Do you always like the things you want?

- Published

Until recently, it was generally assumed that if we wanted something, it was because we liked it. But science is now questioning that idea - and pointing the way to a possible cure for addiction.

Back in 1970 a shabby and shameful experiment was performed on a New Orleans psychiatric patient. We know him only as Patient B-19.

B-19 was unhappy. He had a drug problem and he'd been expelled from the military for homosexual tendencies. As part of his therapy and as an attempt to "cure" him of being gay, his psychiatrist, Robert Heath, hooked electrodes into his brain, attaching them to what - at the time - were thought to be the pleasure centres of the brain.

While the electrodes were attached, B-19 had the power to turn them on, by pressing a button. And press it he did, time after time after time - over 1,000 times a session.

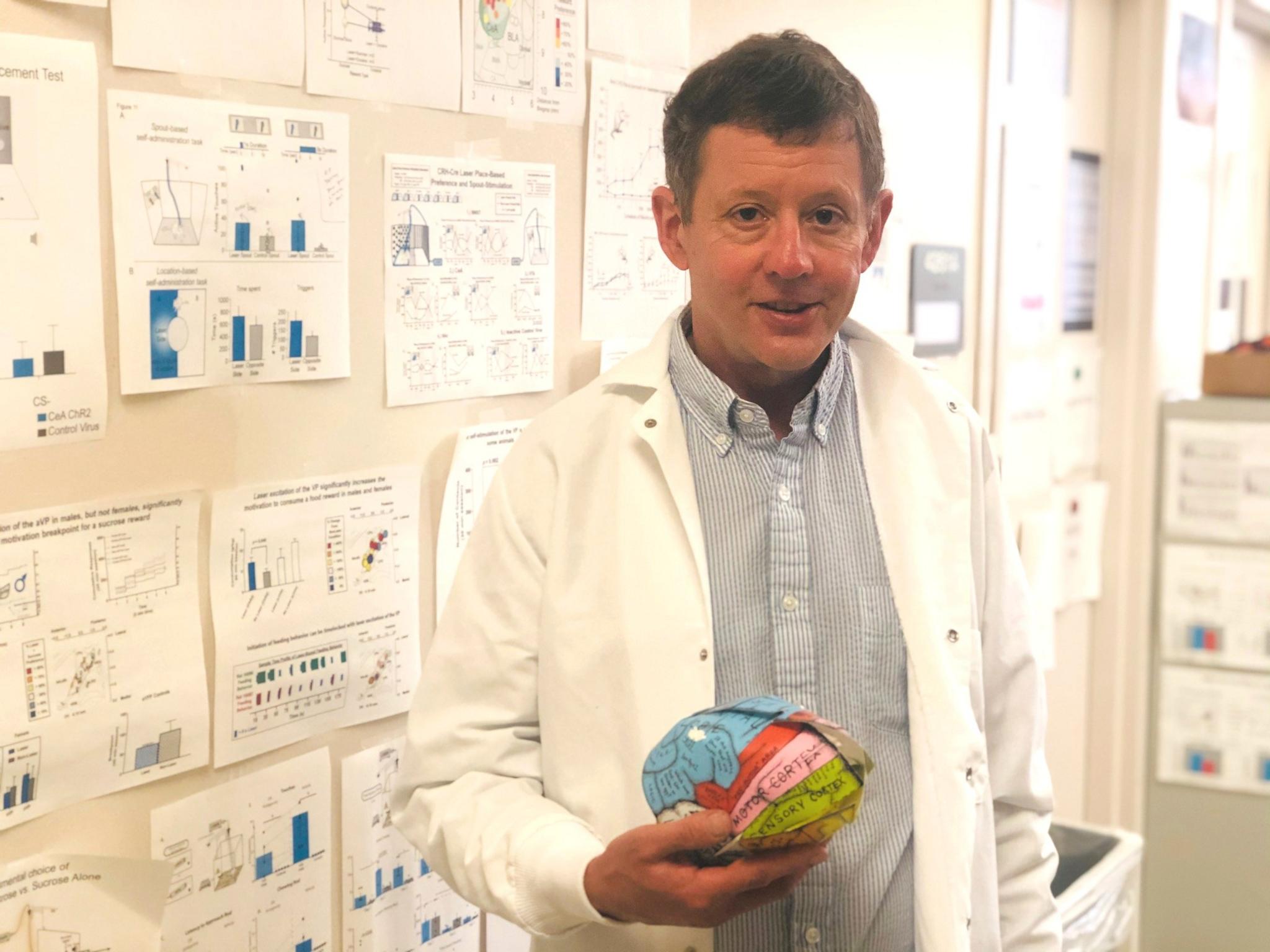

"It made him feel very, very sexually aroused," says Kent Berridge, professor of biopsychology and neuroscience at the University of Michigan. B-19 felt a compulsion to masturbate. With the electrodes on, he found both men and women sexually attractive. And when the electrodes were removed, he strongly protested.

But Robert Heath noted something odd. When he asked B-19 to describe how the electrode made him feel, he expected him to use vocabulary like, "fantastic", "amazing", "wonderful". But he didn't. In fact, he didn't seem to enjoy the experience at all.

So why did he keep pressing the button and why did he protest when the electrodes were removed?

Kent Berridge says we have to start by recognising that although B-19 didn't enjoy the sensations produced by the electrodes, he nonetheless wanted to turn the electrodes on.

But that sounds like a puzzle, a contradiction.

For many years psychologists and neuroscientists assumed that there was no real difference between liking something and wanting it. "Liking" and "wanting" sound like two words capturing the same phenomena. Surely, when I want a cup of coffee in the morning, it's because I like coffee?

Alongside this assumption - that wanting equates to liking - there was another. It was widely believed that there was a system in the brain, involving the hormone dopamine, that drove both wanting and liking. What's more, there seemed to be compelling evidence that dopamine was essential for pleasure. Rats, like humans, love sugary stuff, but when dopamine was removed from their brains and sweet substances were placed in their cages, they ceased to seek these foods out. Cut off the dopamine, it was thought, and you cut out the pleasure.

But was this right? Kent Berridge found another way to investigate the link between dopamine and pleasure. After removing dopamine from rats' brains, he fed the rats a sugary substance. "And to our surprise, the rats still liked the taste normally. The pleasure was still there!" In another experiment at his lab, the dopamine levels were raised in rats, leading to a huge increase in eating - but no apparent increase in liking.

Find out more

You may wonder how a lab-coat wearing scientist can tell whether a rodent is enjoying itself. Well, the answer is that rats have facial expressions rather like humans. When they eat a sweet substance, they lick their lips; when it's something bitter, they open their mouths and shake their head.

So what's going on? Why do rats still like a food they no longer seem to want?

Kent Berridge had a hypothesis, but it was so wild that even he didn't really believe it - at least not for a long time. Was it possible that wanting a thing, and liking it, corresponded to distinct systems in the brain? And was it possible that dopamine didn't affect liking - it was all about wanting?

Rats lick their lips if they like what they are eating and shake their head if they don't

For many years, the scientific community remained sceptical. But now the theory has become widely accepted. Dopamine increases temptation. When I go downstairs in the morning and see my coffee machine, it's dopamine that drives me to brew a cup. Dopamine intensifies the temptation for food if you're hungry, and makes the smoker crave a cigarette.

The most startling evidence that the dopamine system fires wanting, and not liking, comes once again from the unfortunate laboratory rat. In one experiment, Kent Berridge attached a little metal stick to the rat cage that, when touched, delivered a minor electric shock. A normal rat learns, after one or two touches, to stay well away from the stick. But by activating the rat's dopamine system, Berridge was able to make the rodent become engrossed by the stick. It would approach it, sniff it, nuzzle it, touch it with its paw or nose. And even after the minor shock was received, it would return time after time within a five- or 10-minute period, before the experiment was stopped.

Perhaps this explains my coffee-drinking habits. I both want and like my morning cup of coffee. But the afternoon cup of coffee - which somehow I cannot resist making - tastes bitter and unpleasant to me. I want it, but I don't like it.

It's no understatement to say that Kent Berridge has transformed scientific understanding of human desire and motivation.

He argues that wanting is more fundamental than liking. Ultimately, it doesn't matter for the preservation of our genes whether we like sex, or like food. Far more important is whether we want to have sex, and whether we seek out food.

The single most important implication of the wanting-liking distinction is the insight it offers us into addiction - be it to drugs, alcohol, gambling, and perhaps even to food.

For the addict, wanting becomes detached from liking. The dopamine system learns that certain cues - such as the sight of a coffee machine - can bring rewards. Somehow, in ways that are not fully understood, the dopamine system for the addict becomes sensitised. The wanting never goes away, and is triggered by numerous cues. Drug addicts may find their urge to take drugs sparked by a syringe, a spoon, even a party, or being on a street corner.

But the wanting never ceases to go away - or not for a very long time. That makes drug addicts extremely vulnerable to relapse. They want to take the drugs again, even if the drugs give them little or no pleasure. For rats, the dopamine sensitisation can last half a lifetime. The task now for researchers is to find whether they can reverse this sensitisation - in rats, and then hopefully, in humans.

But let's return to Patient B-19. Recall that he had been hooked up to a so-called pleasure electrode and kept pressing the button to activate it, yet, he expressed no delight in the resulting sensations. At the time the psychiatrist, Robert Heath, wondered whether he was poor at expressing his feelings. But now we have a more convincing explanation. It's more likely that B-19 genuinely took no pleasure in the feelings the button aroused, but that he had a compulsion to press the button nonetheless.

As for me, I'm off for my second cup of coffee.

David Edmonds is the presenter of The Big Idea on the BBC World Service. Click here to hear his interview with Kent Berridge from 12 December 2020.