Yami 'Rowdy' Lofvenberg: The top hip-hop dancer who can’t count the beats

- Published

School does not hold happy memories for Yami "Rowdy" Lofvenberg, who was bullied because of her difficulties with maths. Hip-hop dance was her escape and she has since become a creative movement director, performer and hip-hop theatre maker. But recently Yami returned to education - as a lecturer at a London conservatoire.

The arena was set, Yami "Rowdy" Lofvenberg entered the battle.

Her attacks were made with striking agile movements - popping and locking her body. Every fierce beat another step closer to victory.

Armour and shields would not be needed. This was a hip-hop dance battle, and the most creative dancer would be heralded the champion.

Yami competed in London's hip-hop battling scene between 2002-2010, after moving to the UK from Sweden. She says it was a male-dominated environment and women competitors were a rarity.

"I would hear the whispers of, 'This girl, she's so rowdy, she's so too much, she's too loud, she just takes space!"

"Yeah, I'm all of it," was her response. She decided to take the name "Rowdy" as a badge of honour.

Yami compares her performance persona to that of Beyonce's confident alter ego, Sasha Fierce. It was an identity she began to develop growing up in Sweden, she says, but one that stems from her South American roots.

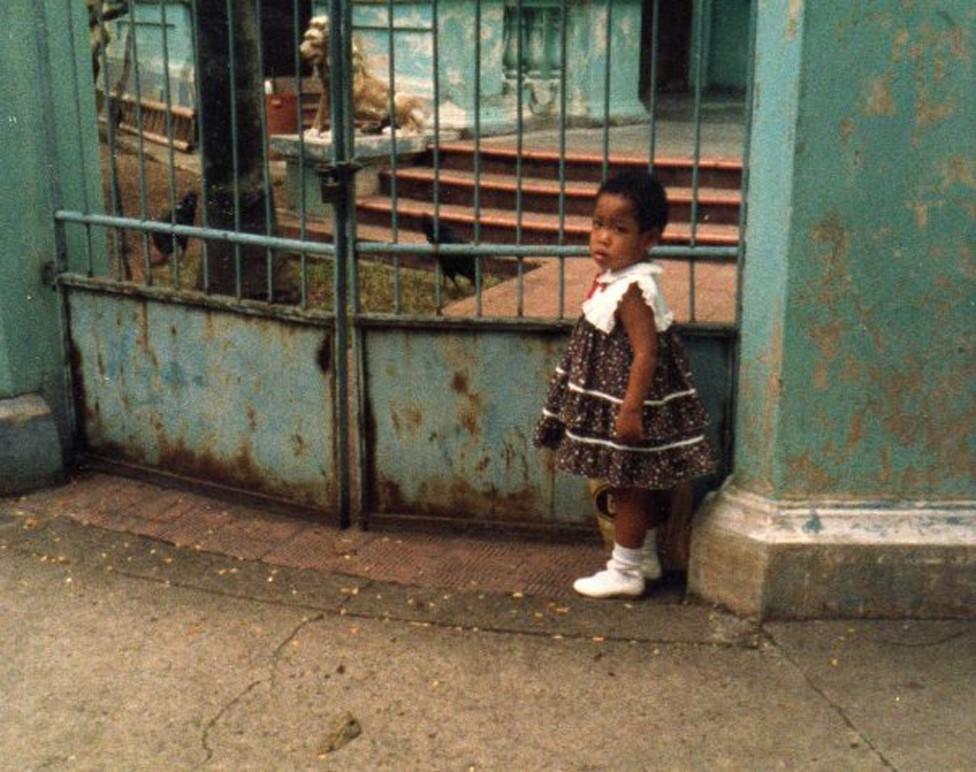

Born in Cali, Colombia, in 1980, Yami was adopted from an orphanage by her Swedish parents at the age of three and went with them to live in Varmdo, an island in the Stockholm archipelago.

"I've always had this spirit in me and I think it's the Latin spirit, I don't know what it is," she says. "But it's the spirit of survival, the spirit of wanting to overcome things. I often stood up for myself when bullies would attack me, I would often talk back. I wouldn't be defeated."

Yami aged three in Colombia

Yami wasn't just Colombian by birth, she was also black. Living in a white area, she says she encountered racism and micro-aggression on a daily basis at school and elsewhere.

"I remember being 10 and being chased down the road by three Nazis with Dr Martens shoes and the bomber jacket and the shaved heads, screaming that they wanted to kill me," she says. "I ran into someone's porch, and closed the door so that they couldn't get in."

Adults watched this happen but did nothing, she says.

Yami travelled to school in Stockholm where she was bullied because she couldn't get the hang of maths.

"It was an old-fashioned school and because they only produced elite children, there was a shame over me, there was a shame that I couldn't understand things," says Yami.

Yami at eight years old

One word became particularly painful for her - the word "stupid".

Although she excelled in anything artistic, physical or creative, like writing stories, Yami says she got called stupid because she had difficulty with counting and arithmetic.

"I just remember not getting a single answer right on a maths test," says Yami.

She would mix up numbers. "For me a two would become a five, and a six would be a nine," she says.

To make matters worse, teachers sent her to study by herself in a dusty library - overseen, but not helped, by the librarian. She still remembers the shame of standing up in class and others sniggering as she was separated from them.

It was like "having a dumb hat on in the corner", she says.

It wasn't until Yami was 18 and in her final year at school that she read an article about a girl who had dyscalculia, and immediately recognised the symptoms in herself.

She found a test and the result seemed to confirm it.

Dyscalculia is a lack of number sense, according to Brenda Ferrie, lead tutor and dyscalculia specialist at the British Dyslexia Association (BDA).

"Humans and animals are born with a built-in sense of number for survival purposes," she says. But someone with dyscalculia "cannot relate the digits in our numerical system with the magnitude or value of a number".

Like dyslexia - which causes difficulties in reading, spelling and writing - dyscalculia is a "specific" learning difficulty, meaning that it can affect people who are otherwise highly intelligent.

A report, external by the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology cited the case of a man with a university degree who could not immediately say which of two single-digit numbers was the larger.

Frequent areas of difficulty for adults include "estimating travelling times and distances, household budgets, changing recipe amounts, discounts, percentages, money and what is good value, and measurements," Brenda Ferrie says.

Defining dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a specific and persistent difficulty in understanding numbers which can lead to a diverse range of difficulties with mathematics. It will be unexpected in relation to age, level of education and experience and occurs across all ages and abilities.

Source: BDA/SASC, external

Someone with dyscalculia might have difficulty answering the question "Would it be sensible to pay £4,000 on a pair of shoes, or £48 on a small slice of cheddar?" she adds. "The relationship or mapping of that number to its value is not there."

Studies suggest that between 3% and 6% of the school population in a range of countries have dyscalculia. But understanding of the condition is said to be about 30 years behind that of dyslexia.

Yami says dyscalculia has had a significant impact on her life.

"I don't remember people's birthdays, I don't remember my home number, I don't remember my bank pin. I sometimes struggle understanding what day of the week it is or what time it is," she says.

"I couldn't read an analogue clock until I was 18 years old, I just couldn't see it."

She says she struggles to understand how near or far something is in the distance and how long it will take to do something.

"Anything really that has to do with numbers, which is quite a lot, would be a constant day-to-day struggle."

After discovering the existence of dyscalculia, Yami says she begged her parents to speak to the school, which gave her a tutor for her final six months of school.

"She would literally be the reason why I could function as an adult," says Yami. "Because she took me out to the actual stores and showed me, 'This is the money, and this is how this money is valued, and this is how you count the money and this is how you weigh bananas.' If I didn't have her I wouldn't have been able to function, because I didn't know how to count."

Dance and performance had always been a release for Yami. As a child she danced around the house, and loved to watch Michael Jackson.

Her first class was in Swedish folk dance, though. "I was like, 'This is not the dance I see on TV,'" she says.

Then, when she was 15, a friend asked Yami if she would go to an open day at the Stockholm Danscenter.

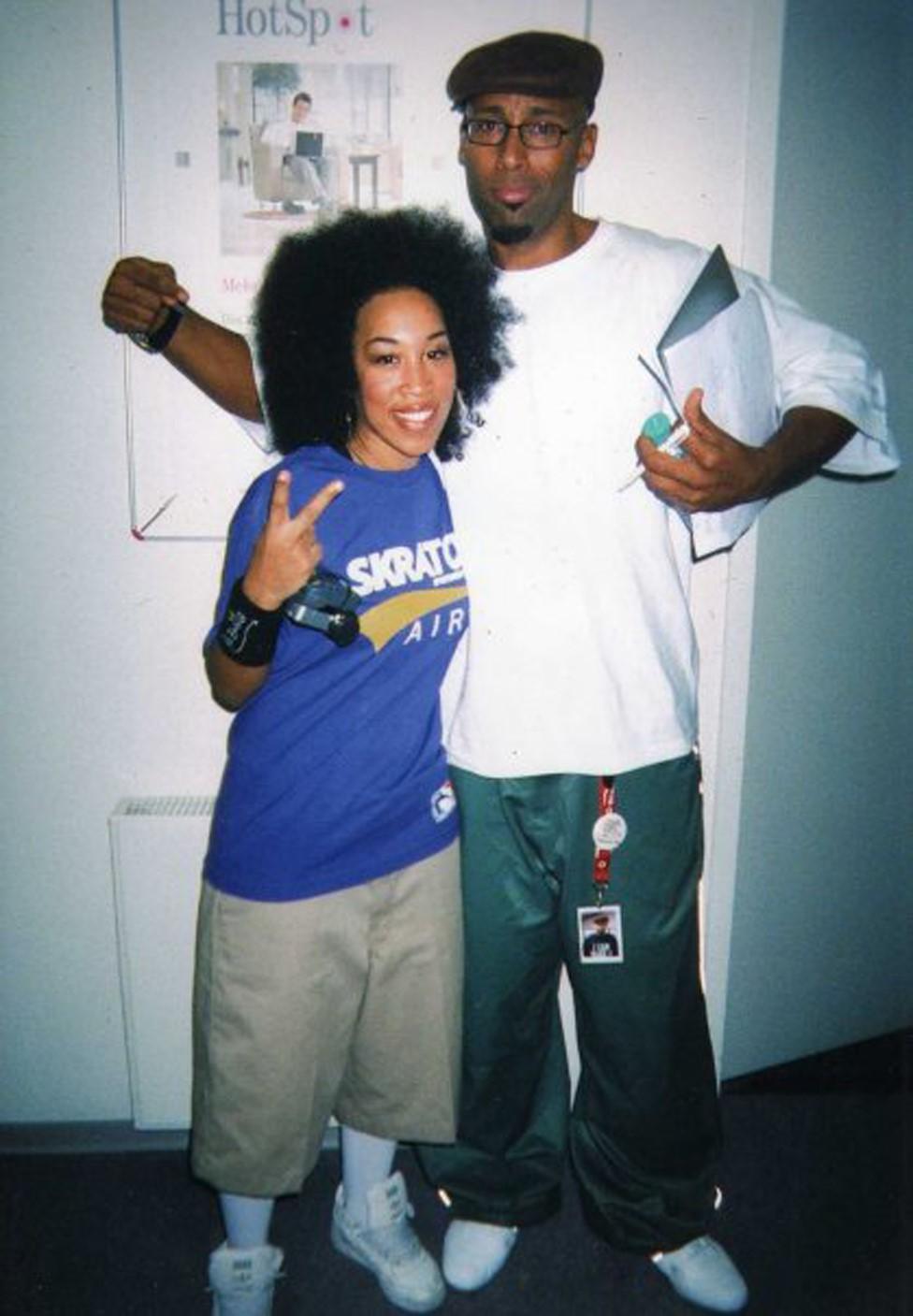

The hip-hop class there was taught by a man called Damon Frost, aka Mr Rubberband Man.

"I saw this big, tall, black American guy," says Yami. "First of all, I had not seen many black people, I wasn't surrounded by black people," she says. And she instantly noticed Frost's "gentleness and smile".

Yami with her dance mentor Damon Frost

Very quickly Yami realised the dance floor was exactly where she was meant to be.

"All I wanted to do - after being bullied in school and bullied in society - all I wanted to do was have a moment of breathing space, and dance was that," she says.

But dancing involves counting beats, and here she struggled.

"I was embarrassed and I was hiding it a lot, trying to pretend it's all fine - like 'I totally knew that that was on the eight and not on the two,'" she says.

"But I also started to see that I could hear the rhythm and [thought], 'Well OK if I can't count, maybe I can go with the rhythm.'"

Luckily, it worked.

Frost would make all the students form a circle at the end of the class. Each one would have to enter the circle and "throw down" - or do battle - either freestyling or performing something they'd learnt.

Yami says having been "beaten down so hard" at school she was nervous. But her fiery alter ego, which later earned her the name Rowdy, came to the rescue.

"This inner spirit would literally flame up," she says. "I would pretend that I was super-confident and would be in everyone's faces."

Her talent was obvious to Frost.

"I don't know what it is, but there's something about you - you have it, and when you know what that is, you are going to be incredible," Yami remembers him saying.

She adds: "It just stuck with me, and I just kept coming to dance class. I kept saving up money so I could go to dance class."

It was Frost who gave Yami her first nickname - Queen of Battles.

Hip-hop dance glossary

Battle: a dance rivalry in which opponents, often in a circle, compete against each other, either as solo artists or as dance crews

Breaking / breakdancing: a street dance form created by young African Americans and Latin Americans in the Bronx, New York, in the 1970s - moves include spinning on your back or head and are mixed with freezes, where the dancer stops moving and holds a position

B-boy and B-girl: a male and female breaker; some say the "B" stands for "Break" and others "Bronx"

Popping: a funk dance style in which the dancer contracts their muscles and relaxes them creating a pop, or jolt, in the movements of the body

Locking: a funk dance style in which the dancer makes fast movements then locks into a position, and continues alternating - often characterised by sharp hand, arm and wrist movements and fluid leg movements

And at the age of 18, she started teaching dance. She also brought other women together to train, and formed what she says she now realises was Sweden's first female hip-hop dance group, Chutzpah Crew.

In 2002, when she was 22, she moved to London where, with dancer Sunanda Biswas, she created Flowzaic, an all-female breaking crew, and then later Funkamental, an all-female locking and popping group. She worked in shops until her reputation grew enough to survive by teaching and performing.

Yami says, "If I don't see it, I have to be it." In other words, she would set out to create what she could not already see on stage.

"There weren't any role models for us," she says in an interview, external for the Hip Hop Dance Almanac. "So we thought we should bring girls together, show that we can work together, and show that we can battle as hard as the boys."

Everything Yami has been through is woven into the steps of her choreography. After she stopped battling in 2010, she began to create hip-hop dance theatre in which she uses a mixture of spoken word, physical theatre and comedy. One of her shows which premiered in 2014, was called Stupid, but the word now took on a very different meaning for Yami.

WATCH: A clip from Yami Lofvenberg's 2014 show, S.T.U.P.I.D.

"I created S.T.U.P.I.D as a kind of rebellion," she says. "How can I change this word that's really affected my life so badly, how can I change it around for someone like me."

So she made the word into an acronym - S.T.U.P.I.D - Someone That Unreservedly Pursues Inspirational Defiance.

"I would never give up, I would never let someone tell me that I am stupid because I am so brilliant at other things that people just can't see sometimes," she says. "And I wanted people to see someone struggling with dyscalculia as an adult, because often we talk about children and how we can help children, but we don't talk about how an adult goes through life with a hidden disability."

In the show Yami performs with other dancers who have learning difficulties, who tell their own stories through solos and group dances.

Yami performing in a dance piece called The Honest Battle

The show she is developing now is also autobiographical and based on her first trip to Colombia in 2013. While there, she taught disadvantaged children and local dance teachers hip-hop dance styles. But her new show will focus on one key meeting in Colombia.

"It talks about when I met my biological mother and how it didn't feel how it was meant to feel, and how stories tell me I'm supposed to feel," she says. "And what happens when you feel nothing, so you're then basically a broken person."

This year Yami started lecturing in hip hop at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. She describes it as a full "360 moment" - a moment when someone who didn't go to university, and had such an awful time at school, herself became a lecturer.

"Just being in a space where I'm in charge of the curriculum… and being able to actually build something up from scratch, and showing how important hip hop is for dance culture, for me it's like that's what I was always meant to do."

Where to get help

When referring to her life, Yami recalls a famous TED talk by educationalist Sir Ken Robinson, external. He tells the story of a young girl who did not fit in at school and was constantly told off for being unruly and fidgeting and not concentrating in class. He explains how her mother asked a specialist for help. After witnessing the little girl move to some music playing from a radio, the specialist advised her mother to take the little girl to a dance class.

In the talk Sir Ken says the little girl was inspired by the fact that she could see other people like her in the dance class, "people who had to move to think".

"She flourished and she became this beautiful person," says Yami, "and it was like, she's not stupid, she's a dancer, and that always reminded me of my story."

The little girl in question was Dame Gillian Lynne - choreographer of Cats and Phantom of the Opera.

After all she has learnt, Yami says her advice for anyone with dyscalculia would be to "never let people dampen your shine, and realise that if they can't see your light, you've got to create your own light and pave the way for others".

Yami will be performing an extract from her new show next year at The Place in London and DanceXchange in Birmingham.

You may also be interested in...

When singer-songwriter Talia Dean was 18 years old, she started experiencing the symptoms of a condition called axial spondyloarthritis - or axial SpA. But the condition has a tendency to be overlooked in women and it took more than 15 years for her to get a diagnosis. By this time, irreversible damage had been done to her spine.

'My back pain was misdiagnosed for 15 years - now I can't dance'