‘If only I’d found out earlier I had pelvic congestion syndrome’

- Published

Sophie Robehmed spent most of 2018 with chronic abdominal and lower back pain, symptoms she'd had before but never for more than a week or so. Then she was diagnosed with pelvic congestion syndrome - a condition no doctor had mentioned in the many years she'd been seeking medical help.

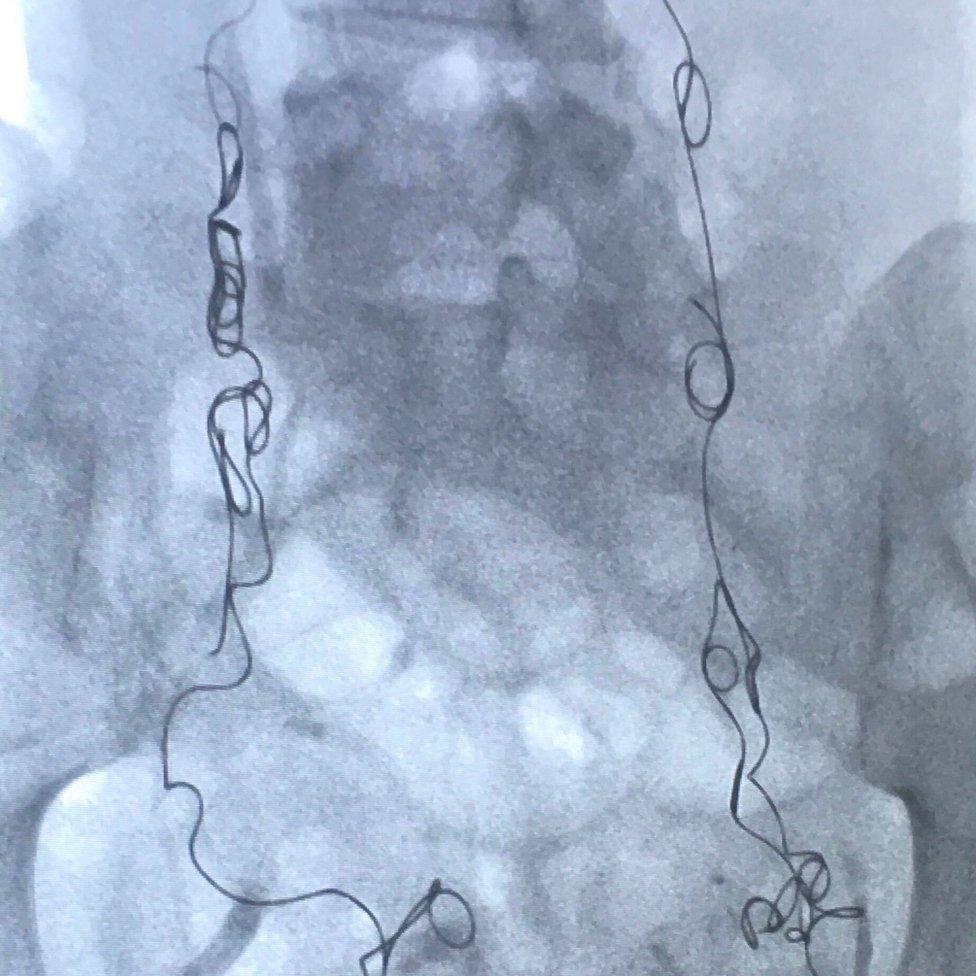

It's Tuesday 14 August 2018 and I am sedated, lying on an operating table, while metal coils are being inserted into my ovarian and pelvic veins via a catheter in my neck.

I have recently been diagnosed with pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS), or ovarian vein reflux as it's also known, a condition that can cause pelvic and ovarian veins to pool with blood, enlarge and press against surrounding organs.

This can cause, or exacerbate, a host of problems - irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), painful periods, backache and fatigue, to name a few - and often brings relentless pelvic pain.

There is no guarantee that the procedure I'm undergoing, known as a vein embolisation, will work. But I've been told that in about 80% of cases it succeeds in reducing or eliminating symptoms altogether, so it feels like my best hope after months of pain.

I began having painful, heavy periods and IBS-type symptoms in my teens, but it wasn't until I was in my 30s that pelvic congestion syndrome was mentioned as a possible cause.

In my early 20s, I was told that I probably had endometriosis, an often agonising condition that is caused by womb lining growing outside the uterus.

A gynaecologist told me the only definitive way to determine whether I had the condition would be to have a laparoscopy, in which a small camera is inserted via a small incision in the abdomen. Alternatively, I could try taking the pill.

As the laparoscopy felt like a drastic and invasive option at the time, I decided to try the pill.

It definitely helped to reduce the severity of my symptoms, and I am still taking it today - but it has never completely solved the problem, so I have undergone numerous investigations over the years.

I've had myriad scans: CT, MRI, transvaginal ultrasound.

I have been tested for food intolerances, and I've tried elimination diets.

I even had tiny cameras poked down my oesophagus and into my colon on the same afternoon.

When I had a flare-up, I was usually in pain for up to a week at a time, but towards the end of January 2018, I had a new experience.

June 2018: Recovering in hospital after the laparoscopy

This time, it began gradually with dull abdominal and lower back pain over a period of days that worsened until I was hit with the familiar aggressive cramps in my stomach and lower back.

In between being bent over in bed and going to the toilet, I was also sick.

A persistent dull ache followed the flare-up - but this time, it didn't go away.

I was signed off work and given oral morphine. A blood test also revealed a high level of inflammation in my body but it wasn't clear why; a GP thought I was probably fighting an infection.

A lot more uncertainty followed. I had many appointments and was given a lot of prescription drugs - and on occasions, antibiotics for suspected urinary tract infections.

I often dragged myself into the office, pained and worn out.

Then, in June 2018, I finally had the laparoscopy that I had decided against eight years earlier.

What is PCS?

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is a term to describe varicose veins in the pelvis area and can lead to chronic pelvic pain in women.

The pain is thought to be due to the varicose veins surrounding and pressing on the ovaries and sometimes the bladder and rectum. Women may experience a dragging sensation in the pelvis and a feeling of fullness in the legs. Women may also notice changes in their urinary and bowel habits, including a worsening of existing stress incontinence or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.

There are medicines available for women, which can reduce pain and the size of the varicose veins. If this does not work, pelvic vein embolisation is an option, in which veins can be sealed and blocked.

Prof Andrew Horne, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

When I came around from it, my gynaecologist told me that there was no sign of endometriosis but that I did have congested veins.

My latest transvaginal ultrasound report had queried "pelvic congestion" for the first time and my gynaecologist had now seen evidence of this for himself, but he didn't seem convinced that these veins could cause the level of pain I had been experiencing.

Still, he offered me a referral to a vein expert - Dr Aidan Shaw, a consultant interventional radiologist.

He went on to confirm that I had pelvic congestion in my left and right ovarian veins and in branches of another vein in my pelvis, the iliac vein.

While PCS remains a relatively niche diagnosis, the symptoms it can cause are common.

An X-ray shows the coils inserted in Sophie Robehmed's veins - the dark column in the centre is her spine

"Chronic pelvic pain makes up to 10-40% of gynaecological outpatient department referrals but it is not known what portion can be attributed to pelvic congestion syndrome," says Prof Andrew Horne, consultant gynaecologist and spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

"More research is required into this gynaecological condition, with awareness currently lacking."

Aidan Shaw, my former consultant, says some doctors are unfamiliar with pelvic congestion syndrome, and others are sceptical about its existence.

"PCS can present as a multitude of symptoms and signs that I think are often ignored or misdiagnosed by doctors and nurses," he says.

"It takes a clinician to think and believe in the diagnosis, and there are some who do not believe in the condition, sadly."

PCS and pregnancy

PCS is more common in women who have had at least one pregnancy because this increases blood flow to the pelvic area, and ovarian veins can be compressed as the womb expands. Either of these things can cause valves in the veins to stop working, and blood to flow backwards, leading to PCS.

Other causes include vein obstruction or the absence of vein valves altogether.

Although less common, men may have a version of PCS, diagnosed through visibly enlarged veins in the scrotum, known as varicoceles.

As an interventional radiologist, Aidan Shaw uses a variety of medical imaging techniques to diagnose problems, and then treats them using minimally invasive procedures. He says he and his colleagues are constantly trying to increase public awareness of what they can do.

"The only way is education - for doctors, the public, publications - and persistence," he says.

The embolisation I had in August 2018 blocked my congested veins with metal coils so that they could no longer fill with blood, enlarge, and cause me pain.

Since then, my symptoms have greatly improved, but I can still have nasty period pains. In January 2020, they were worse than usual, and I was given an MRI scan to check for adenomyosis, which causes the uterus's inner lining to break through its muscle wall, and can also lead to congested veins.

Thankfully, there was no sign of this condition - or any evidence of new congested veins either.

During my follow-up telephone consultation, I asked my gynaecologist whether she thought my pain and irritable bowel symptoms over the years could all have stemmed from PCS and bad periods, or whether there might have been another problem too. After more than a decade of medical tests, I craved clarity about the state of my own body from the voice at the end of the phone - but she told me that she couldn't answer my questions with any real certainty.

It wasn't what I wanted to hear but, more than a year since that conversation, and nearly three since the embolisation, I'm doing well. I feel lucky that I finally got diagnosed and was treated successfully, and I will forever be grateful to those little metal coils that have made a profound difference to my life.

You may also be interested in:

Loretta Harmes hasn't eaten for six years, but she hasn't lost her passion for cooking. Even though she cannot taste her recipes, she has a growing following on Instagram, where she's known as the nil-by-mouth foodie.