'I could have been a racist killer'

- Published

In his late teens, Mike became a Nazi. Now, only six years later, he is a supporter of Black Lives Matter - and it worries him deeply to think how close he came, at the angriest stage of his life, to going out with his gun and shooting people.

When Mike locked eyes for a brief moment with the man who had just fallen to the ground, he could tell that he was going to die. It was a frantic night in downtown Oakland, California, and the wind was sharp with the sting of tear gas as it whipped palm trees up into a frenzy.

Three days after the murder of George Floyd, protests in support of Black Lives Matter were breaking out across the US.

Mike had been protesting with his girlfriend but as night fell and the police started firing rubber bullets and tear gas, they decided to leave. They were walking back to their car, along streets filled with the black smoke of burning rubbish bins, when they saw a white van pull up. Then they heard the gunshots.

The van pulled away as a man in uniform slumped to the ground. Mike moved towards him, trying to remember the first aid training he had learned in the military. But a police car arrived and a jittery gun-wielding officer jumped out and ordered Mike to leave.

Later he learned that Dave Patrick Underwood, a federal officer who had been guarding the courthouse, had died at the scene. More than a year on, it still haunts Mike that he couldn't do more to save him.

By coincidence, Mike had a connection to Underwood; he had been marching that day with members of his family.

But he was also connected to the man who was later charged with his murder. Steven Carillo was a sergeant at the same California Air Force base where Mike had enlisted just a few years earlier.

And that wasn't all.

Mike had a secret. At home in his wardrobe there was a uniform made of grey-green khaki fabric, with a Nazi symbol on the collar.

Mike kept it hanging there to remind himself of the person he used to be, someone who wanted to go out and kill people.

Like Carillo, Mike had fallen down the rabbit hole of extremism, and become a follower of America's violent far-right.

In the summer before Mike's final year at school he watched as the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests rolled out across the US, but taking part was the furthest thing from his mind. "I thought they were Satan incarnate," he says.

He had just met a new friend through a messaging group online. Paul (not his real name) invited Mike to visit his home, where he lived with his parents. It was an ordinary house on a quiet cul-de-sac in an upmarket suburb of a major US city. They were meeting to "shoot some propaganda videos".

Paul opened the door in full Nazi uniform. He took Mike straight to his garage. "It was just like a clothing store for Nazis," Mike says. The walls were lined with weapons - ammunition, cartridges and many guns."

Paul had gathered a few other young men for the shoot. They loaded guns and ammunition into a truck and drove out to some nearby hills.

"We were on a state park firing semi-automatic and automatic weapons, filming and running around in Nazi uniforms," Mike says. Then the park rangers appeared. Paul was annoyed.

"He was just kind of standing there and he's not really having any of it. He's not wanting to listen to this government authority telling him that he cannot do what he thinks he's entitled to do, which is make videos and pretend to be the Wehrmacht [the armed forces of Nazi Germany]."

The rangers confiscated all the guns they could see, but the boys had hidden some of them and just loaded them back in the truck once they were alone again. Then they went back to Paul's house and hung out with his parents - still wearing their Nazi uniforms.

Mike was 17 and says he had become the perfect vessel for toxic extremism.

He had spent his childhood in a small, rural, mostly white town. Days were spent kayaking on the lake or cycling around town with his tight-knit group of friends. Adults and kids would hang out together and dinner parties and barbecues were spontaneous. It was a place where everybody knew everybody.

But Mike's stepfather was an alcoholic who could lash out violently, and when Mike was 12 his mother got a divorce and moved with the children to another part of the country.

Suddenly Mike was living in a sweltering, multi-racial urban neighbourhood, and he hated it. "There were people there who didn't look like anything that I had ever seen before, the food was different, the water tasted different, everything just completely different."

They were also much less well off now, and the stepfather - whom Mike had been close to, despite his violent outbursts - never kept a promise to visit the children.

All this made Mike angry, and he found an outlet for that anger in the alt-right.

Encouraged by the father of a friend, Mike began listening to right-wing talk show host Sean Hannity, and when he searched for similar content online he found alt-right videos and podcasts on Facebook and YouTube. Social media algorithms were already creating what is known as the rabbit-hole effect - leading him to content that became more and more extreme.

Here he was told, for example, that divorce was a Jewish conspiracy meant to destroy the ideal white family. "For whatever reason, for me that was easier to believe than that my stepdad was a degenerate alcoholic," he says.

Eventually Mike migrated to the darkest corners of the internet - to white nationalist message boards on 4chan and 8chan. These sites were like a social club for racists, Nazis and white nationalists, where people could say the N-word while getting to know one another, Mike says. He started exchanging messages with a group of neo-Nazis in the San Francisco Bay area and that is how he ended up on Paul's doorstep that summer afternoon.

"I was just looking for a place to put all my anger," Mike says. "And it found a perfect home."

A year later, Mike finished school. When he didn't get into his preferred universities, he said he would join the Navy instead, but his mother was against the idea. They settled on a completely different plan - Mike would go to a business school in London.

In the UK, Mike expected bowler hats and gentlemen - his image of London was like something out of a Victorian novel. The reality was very different. His school was in Whitechapel, an area with a vibrant Muslim community.

"I was an 18-year-old, radical white nationalist deeply fearful, deeply Islamophobic and I arrived in Whitechapel at a flat that was sandwiched between the Royal London Hospital and the East London Mosque," he says. "I definitely didn't see the diversity there as a positive thing, I looked at it as an example of everything that was wrong in the world."

During his time in London, Mike sank deeper and deeper into white nationalism. Most of his activity was online - he digitally stalked and harassed American left-wing celebrities for months with a team of other extremists - though one day he also walked up to a mosque and dropped a packet of bacon on the doorstep.

He stopped going to classes and after a few months he got a letter from the Home Office that his student visa was going to be revoked.

One afternoon in April 2017, he was on his way to meet some friends at a pub on Parliament Square. While he was on the train passengers were told that Westminster station had been closed because of a police operation - they had to get off at the station before.

A vehicle had mounted the footpath on Westminster Bridge at 70mph and mowed down pedestrians. The driver then got out and stabbed a police officer; six people died, including the attacker, and 50 were injured. Mike emerged from the Tube station to a scene of panic. The sight of two children wrapped in foil blankets handed out by the emergency services is imprinted on his mind.

At this stage, IS was still a powerful force in the Middle East. It said it was responsible for the attack, one of a number carried out across Europe while it was at its most influential.

Mike tried to sign up to the military the next day. Some of the white nationalists he had been speaking to online were military men and he took his cue from them. He was rejected from the RAF because of his nationality, but within weeks he was back in California enlisting with the USAF.

"I was supercharged, like really supercharged. I mean, there was no doubt in my mind that I wanted to go to somebody else's country, whether it be Iraq or Afghanistan, put on a uniform and pick up a gun and kill them."

In the weeks before he began his military training, he spent hours in his garage drinking and chain-smoking cigarettes, full of rage.

"I almost always had a gun with me," he says. "And I was at the point where if somebody had told me to do something, I would have done it."

In that period, he could have become a Steven Carillo, he now fears - though there was another incident later in 2020 where this feeling hit him with particular intensity.

A few months after the protests in Oakland, rioting engulfed Kenosha in Wisconsin when a black man was shot in an encounter with police.

A 17-year-old boy called Kyle Rittenhouse joined a vigilante group formed to defend the city from what an organiser called "evil thugs". He shot three people with an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle and is now on trial accused of intentional homicide and recklessly endangering safety.

Mike found it hard to read about.

"I look at that young teenager and I'm like, 'Wow, that was really close to being me,'" he says.

In February this year, the Pentagon issued a "stand down" against extremism - an order to leaders across the military to address extremism in their troops. At the same time, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin set up a working group to determine how to spot "insider threats" and explained that prospective recruits would now be screened for extremist affiliations.

These moves came after early analyses of those arrested in the Capitol Hill riots on 6 January suggested a troubling proportion were acting or former servicemen and women - including Ashli Babbitt, an Air Force veteran killed by a police officer as she tried to break through a barricaded door.

A 2020 Military Times online poll of 1,108 readers on active duty, found that just under a third had seen signs of racist or white supremacist behaviour, external within the military.

Among those charged with offences in 2020 - apart from Steve Carillo - were US Army private Ethan Melzer, accused of preparing the ground for a deadly ambush on his unit by sending information to a neo-Nazi group, and three extremist veterans accused of carrying Molotov cocktails to throw at police during a Black Lives Matter protest in Las Vegas.

But perhaps surprisingly, for Mike the military would be the start of his journey out of far-right extremism.

In late 2017, he was in the second month of his training, stationed deep in the woods of Missouri.

"I was just stuck in the middle of nowhere with all sorts of people from all over the US - including black guys, Jewish guys, a guy from Guam who taught me how to spear fish," he says. "I was making friends with people who I would never have considered being friends with before."

He found military boot camp difficult. The hours were gruelling and the lack of autonomy - the control that his superiors had over his every move - was hard to deal with.

"It's one thing to be some kid, chain-smoking and reading 4chan and getting riled up in your garage," he says. "To then finding yourself in the middle of nowhere, on an Air Force base that you cannot leave and people are screaming at you."

He was miserable and tried to quit basic training six times in eight weeks. His mother wasn't talking to him - he thinks perhaps she knew he had joined the military for the wrong reasons.

Letters were a lifeline for recruits but in the first five weeks Mike received none. When the other trainees had time each week to read their letters, Mike sat alone wallowing in his misery.

One day another recruit, who was black, noticed this. "Hey man," he said, picking up a Bible. "Let's pray together."

It was one of many small gestures that helped Mike to survive basic training and ultimately changed his outlook on life.

"Why are you helping me?" Mike thought. "I thought you wanted to destroy me."

Over the next few weeks, this recruit and another young Jewish man would support Mike through his darkest moments, with a friendly pat on the back when he was struggling or a quiet, "Hey man, you can do this."

During training he was also removed from the echo chamber that had been reinforcing his racist beliefs. He didn't have time to go online and without the toxic propaganda that had filled his days, hate was loosening its grip on him.

By the time he emerged from basic training Mike knew he didn't want to be in the military. He spent several months working at an Air Force base, but he was deeply depressed.

He reached his lowest ebb shortly before he was due to be sent to Afghanistan.

"I knew I was being deployed. I was under a lot of stress, [there was] just too much alcohol about one night and access to a firearm."

He came close to killing himself and was put on unpaid medical leave. It's an episode he finds difficult to discuss.

Although in his case basic training helped him break away from extremism, Mike doesn't think it's a coincidence that a number of those involved in far-right violence in recent years served in the military.

He believes that some extremists may join the military, as he did, eager for an opportunity to kill people of a different race.

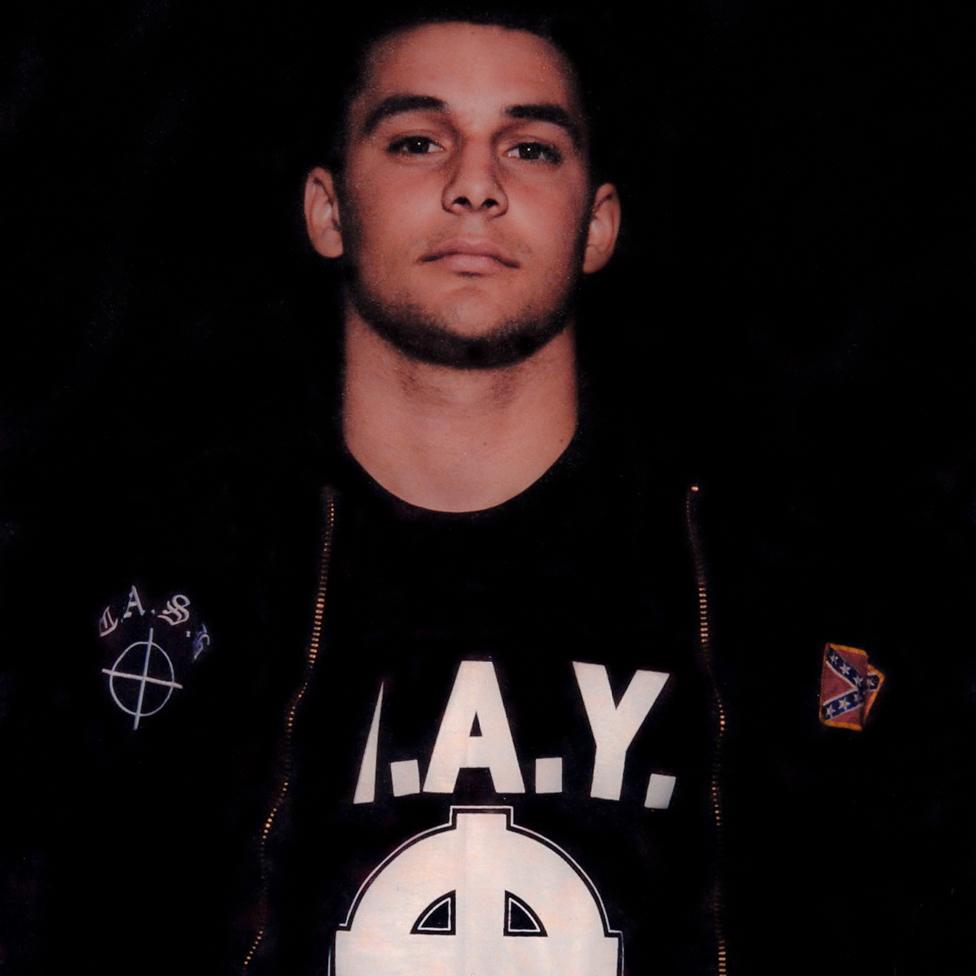

Mike's USAF uniform and Nazi uniform hanging side by side in his room

Others, he suggests, sign up because they think the training will help them overthrow the state, while a third group become disillusioned and radicalised as a result of their experience in the ranks.

"They feel taken advantage of, not understood and lied to," he says.

One of these is a friend who Mike has seen on social media showing support for an anti-government militia group. "He served for 16 to 20 years and he's been to two wars - two wars that were about a lie," Mike says, referring to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Last month the Institute for Strategic Dialogue released a report looking at discussion of the military by far-right extremists on the messaging app Telegram. They found a small number of extremists claimed to be veterans, but they also saw that the military was generally discussed in a negative light, external. "This is largely due to the perception that the US's interventions abroad serve Israeli interests rather than those of the white race," the report says.

Mike also started to believe that America's wars were pointless, but he accepted his racism was pointless too.

"I started kind of realising, about 70 years later than everybody else, that Hitler was clearly wrong," he says.

As Mike's ideas on race started to change he got in touch with Christian Picciolini, a former neo-Nazi who now channels his energies into deradicalisation.

"He told me to practise empathy, being non-judgmental, being honest, and always being self-reflective - essentially to find a way to make good happen," Mike says.

He started working at a music venue and became enamoured of the punk rock scene. It was the outlet that he needed for anger he'd built up from his unsettled childhood. Punk became his saviour.

"My punk rock community has been the one of the biggest things in getting me out. I think how vital it is to have an outlet and to have a group where you feel like you belong. But a constructive group," he says.

After his medical leave ran out, Mike didn't return to the military and was classified as Awol. Then, last December, to his surprise, he was honourably discharged.

Sometimes he worries that extremism still has a grip over him. Towards the end of 2019 a deli that he was working in was robbed by two young black men and an older woman was assaulted, Mike tried to stop them and they pulled out a gun. Later that night Mike recognised the same ugly, dehumanising, racist ideas crowding his thoughts again but he fought against them.

"I've made continual efforts to be anti-racist, to be actively anti-racist. But it is difficult and I don't want to pretend like it isn't."

As he clawed his way out of the extremist rabbit hole, he saw some Americans fall deeper into it. Oakland and Kenosha weren't the only places where Black Lives Matters protesters were injured and Mike was horrified by the attack on Capitol Hill.

The US is a loosely bound "union of otherwise warring clans", he says. "And when you decide to drop a match on it, it can get incredibly dangerous. I've already seen a tremendous amount of violence."

Mike wants people to understand how easy it is in America today for extremist ideology to take over someone's life.

"I was a teenager with basic internet access in suburban California, and I became radicalised enough to want to commit acts of violence against people because of the colour of their skin or their religion," he says.

"The thing I want people to know is that I was a Nazi. Not in 1939 Bavaria but in modern-day America."

Mike is a pseudonym

You may also be interested in:

Just one conversation was enough to recruit Christian Picciolini into the neo-Nazi movement, but it took him years to get out. To make amends for his wrongdoing, he has spent the last quarter of a century persuading hundreds of others to make a break with extremism.