Hackers and hippies: The origins of social networking

- Published

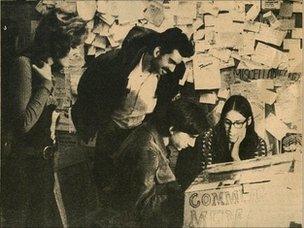

The first Community Memory terminal at Leopold's Records in 1973

People that have been to see last year's blockbuster The Social Network, could be forgiven for thinking that the rise of sites like Facebook started just a few years ago.

But to find the true origins of social networking you have to go further back than 2004.

In a side street in Berkeley California, the epicentre of the counterculture in the 1960s and 1970s, I found what could well be the birthplace of the phenomenon.

Standing outside what was once a shop called Leopold's Records, former computer scientist Lee Felsenstein told me how, in 1973, he and some colleagues had placed a computer terminal in the store next to a musicians' bulletin board - of the analogue variety.

They had invited passers-by, mainly students from the University of California, Berkeley, to come and type a message in to the computer.

Back then, it was the first time just about anybody who was not studying a scientific subject had been allowed near a machine.

"We thought that there would be considerable resistance to computers invading what was, as we thought of it, the domain of the counterculture," Mr Felsenstein explained.

"We were wrong. People would walk up the stairs and we had a few seconds in which to tell them, 'would you like to use our electronic bulletin board, we're using a computer.'

"And with the word computer their eyes would lighten, brighten up and they'd say: 'wow, can I use it'?"

Soon the machine was filling up with messages, everything from a poet promoting his verses and musicians arranging gigs, to discussions of the best place to buy bagels.

The project, called Community Memory, survived on and off for more than a decade, installing more computers across the San Francisco area. But it was not until the 1980s that much of a crowd came to online life.

Network crisis

The Well, another Californian community, was the result of the marriage between hippies and hackers, counterculture and cyberculture.

It was born as a result of a meeting between Dr Larry Brilliant, a doctor working for the World Health Organization (WHO), and Stewart Brand, originator of the original 1960s hippie bible, the Whole Earth Catalog.

Dr Brilliant had somehow pieced together a network to deal with a crisis when a helicopter carrying out a WHO survey in the Himalayas needed a new engine.

Using a very early Apple computer, supplied by his friend Steve Jobs, he had managed to stage perhaps the world's first online tele-conference.

"Steve had given me an acoustic modem," he explained. "And we networked in and suddenly we had a donation of a spare engine from Aerospatiale, Pan Am offered to fly the engine into Kathmandu, and the RAF volunteered to transport it over land to the downed helicopter, and 72 hours later the engine was in Nepal."

He decided this could be the foundation for a business, and when he took the idea to Stewart Brand, he agreed.

Soon, his Whole Earth Catolog had become the Well - the Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link.

"It turns out that we were one of the discoverers of what a low threshold things are on the net," Mr Brand told me for the Radio 4 series The Secret History of Social Networking.

"You could just haul off and start something like this with nothing other than a leased machine which we got from Larry, and a bit of lousy software, and we were off and running."

The Well brought together hackers, hippies and writers from across the San Francisco Bay area in online conversation about everything from technology and politics to the meaning of life.

After meeting online, they ended up holding parties; an early sign that the real and virtual worlds could merge.

"Unlike Facebook, we got to know each other online before we knew each other face-to-face," said Howard Rheingold, the writer who first coined the term virtual community and an influential member of the Well.

"A lot of face-to-face communication grew into relationships. People met and got married, and marriages broke up, when people got sick they got support, when people were dying they got help."

'Global village'

The Well was given added momentum because it became a meeting place for Deadheads, fans of the Grateful Dead.

It also gave John Perry Barlow, a lyricist for the band, and later founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, his first introduction to online communities.

"I found a zone where people from all over the planet could have a conversation on a 24-hour basis."

And after 30 years spent exploring virtual communities, he said, none come close to the original.

"Facebook is more like the global suburbs than the global village," he said. "And what you say on Twitter lasts 20 minutes. If Christ had tweeted the sermon on the mount, it might have lasted until nightfall.

"I think the last one I saw that really felt like it might become the real thing was what was there on the Well."

But it was not just in California that the idea of meeting and socialising online took root.

In Europe, Britain's Prestel and France's Minitel - gave millions of telephone users their first taste of online communication.

In many other places, the Bulletin Board System (BBS) movement became a focus for intense communication about anything and everything for anyone who could afford a personal computer and a modem to dial in.

Jason Scott, who was a teenage BBS user in White Plains, New York, in the late 1980s, said the idea that BBS users were social misfits who lived their lives online is misplaced:

"The computer was a means to an end," he explained.

"Because long-distance phone calls were so expensive, the BBS systems were very local. You would communicate with other people, send messages, upload files, inevitably someone would say 'hey, let's go down to the local pizza parlor'."

He is still friends with some of the people he met in this way more than twenty years ago.

Like many users of early networks, Jason Scott is now a keen user of their modern equivalents - his cat Sockington, external is now the most popular pet on Twitter. But the pioneers do not believe the story is over.

Mr Felsenstein, who can claim to have started it all, says social networking has changed his life. He met his wife online, and he went on after Community Memory to have a career in computing.

"Mind you," he said, "there's lots of room for improvement. I don't believe that what we see is the best that could ever be."

The Secret History of Social Networking is a three-part series for BBC Radio 4, starting on Wednesday 26 January at 1100 GMT. Listen again via the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast.