Alan Turing: Is he really the father of computing?

- Published

A series of celebratory events is taking place this week to mark the centenary of computer pioneer Alan Turing's birth.

To mark the occasion the BBC has commissioned seven articles to explore his achievements. This third essay questions how influential his pioneering work on early computers proved to be in their later development.

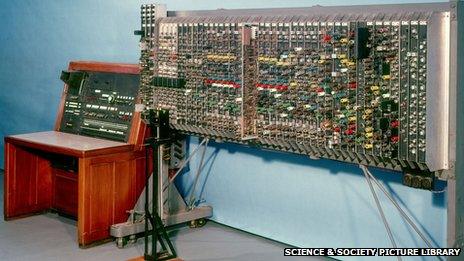

The Ace Pilot, seen here at the Science Museum in London, was built after Turing had walked away from the project

When Alan Turing arrived to start work at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) at Teddington, south-west London, he was 33 years old.

It was October 1945 and he was placed in a section by himself, with instructions to design a new type of calculating machine.

A few months before, a team of mathematicians and engineers at the University of Pennsylvania had produced an extraordinary report for the US Army, outlining the design of Edvac: the Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Computer.

Edvac was novel. It was what we would now recognise as a universal, stored-program computer and it opened up the possibility of applying high-speed automatic digital computations to a wide range of problems.

Technical detail

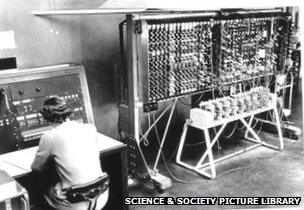

The Pilot Ace was operated from a console that sat next to the computing device

The great and the good of the scientific world on both sides of the Atlantic quickly saw the strategic possibilities of building such a universal computer, which is why the NPL recruited Alan Turing to design a British version.

Turing needed no prompting. He had developed his own ideas on the theory of universal computation, in a complicated paper entitled On Computable Numbers, published in 1936.

While this addressed a philosophical problem in pure mathematics, Turing had certainly realised that there could be practical applications.

His Proposed Electronic Calculator, a document describing what the NPL management were soon calling Ace - the Automatic Computing Engine - contained more technical detail than the Americans' Edvac Report.

'Giant brain'

While the Ace used the same notation as Edvac, Turing's report went much further in dealing with software issues and in predicting future non-numeric applications of computers.

Throughout 1946 and 1947, the NPL management made unsuccessful efforts to set up an electronics group to build Turing's paper design for Ace.

The popular press got wind of the plans for a giant brain, putting more pressure on the management. In the spring of 1947 the American Harry Huskey, on a year's visit to NPL, came close to starting the construction of a Pilot model of the Ace design but Turing disagreed with the scheme.

In the autumn of 1947 a disillusioned Turing took himself off to Cambridge University for a sabbatical year.

Production version

The Pilot Ace was first shown to the public in 1950 and was used for five years, before being donated to the Science Museum

It was not until the spring of 1948 that, in Turing's absence, construction of the Pilot Ace computer began in earnest.

It eventually ran its first program in May 1950. The English Electric Company then took the design and marketed a production version known as the Deuce computer from 1955 onwards.

Meanwhile, at least five other teams in the UK, and many more in America, had also started to design stored-program universal computers along the general lines of the Edvac Report.

The first of these to work was a small computer that came to life in the electrical engineering department at Manchester University in June 1948, to be followed by a larger machine at Cambridge University in May 1949

Although these projects bore little relationship to the details in Turing's Ace proposal, he was sufficiently interested in work at Manchester University to take up a post in its mathematics department in October 1948.

Here he contributed to the design of the machine's input/output systems and suggested enhancements to the instruction set.

With government support, the developments were taken up by local engineering firm Ferranti, which, in February 1951, delivered the Ferranti Mark I - believed to have been the world's first commercially available computer.

Limited influence

Until his death in June 1954, Turing used the Ferranti Mark I at Manchester for developing mathematical models of embryonic growth, an exciting new field of research known as morphogenesis or "the development of shape and form in living things".

Like many other brilliant minds, Turing's significance was widely appreciated only after his death.

He is often called the "father of computing", but was this really the case at the time of conception?

Turing's former Cambridge tutor and leader of the wartime Colossus development at Bletchley Park, Prof Max Newman, described him as "one of the most profound and original mathematical minds of his generation".

Turing (right) made a small contribution to the design of the Ferranti Mark I computer.

And yet, when asked what influence Turing's On Computable Numbers paper had in the early days of computer design, Newman replied: "I should say practically none at all."

Complex software

It was not until the late 1960s, at a time when computer scientists had started to consider whether programs could be proved correct, that On Computable Numbers came to be widely regarded as the seminal paper in the theory of computation.

As for Turing's Pilot Ace, it was in many ways groundbreaking, faster than other contemporary British computers by about a factor of five, while employing about one-third of the electronic equipment.

Ironically, Harry Huskey returned from NPL to lead a computer design group at the US National Bureau of Standards, where his Standard's Western Automatic Computer (Swac), first working in August 1950, was faster than Pilot Ace while being much easier to program.

Indeed, the complexity of writing programs for the Pilot Ace and Deuce was one of the reasons why Turing's design did not have more influence.

Alan Turing is rightly regarded as a national treasure - even an international treasure.

But his codebreaking work at Bletchley Park, and indeed Turing's Ace design, exerted little influence on commercially viable computers as markets began to open up in the late 1950s.

Nevertheless, Alan Turing's ideas remain to this day embedded in the theories of both codebreaking and computing.

<italic>Simon Lavington is the author of Alan Turing and his Contemporaries: Building the World's First Computers and a former professor of computer science at the University of Essex.</italic>

- Published18 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012