Alan Turing: Gay codebreaker's defiance keeps memory alive

- Published

Experts, gathered at a Turing centenary conference in Cambridge, give their views on what his greatest intellectual contributions are

Did Alan Turing's death come as a shock to the Britain of 1954? To close friends, it was a trauma which even after decades remained unhealed.

But to the public it was virtually unknown. He was no icon of the early computer industry. In 1954, and in the succeeding decades, there was little to suggest a connection with practical developments, which anyway were largely assumed to be American in origin.

In pure mathematics his name was not forgotten.

In philosophy the Turing Test was talked about - and reflected, for instance, in Arthur C Clarke's 2001.

But the overall picture was of a purely theoretical figure. As a Fellow of the Royal Society, he received a long scientific obituary in 1955, but his practical computer role was given minimal attention, and this set the tone for all later accounts.

Modest approach

Turing largely allowed himself to be written out of the story in this way.

Details of Turing's codebreaking activities at Bletchley Park were not disclosed until the 1970s

Although he briefly figured in early newspaper accounts of British computers, and spoke on BBC radio twice - unfortunately, without any recording being kept - he never put himself forward as the person who had conceived of the universal machine in 1936, and shown how to make it practical 10 years later.

Nor, it seems, did anyone press him on this question. After an athletics meeting on Boxing Day 1946, a sports reporter, who was aware of his life as designer of the "electronic brain", interviewed him.

Turing was reported as "diffident" about his prowess, and credited Americans for the "donkey work".

This self-effacement, mixed with a dark hint that he had actually contributed something better than "donkey work" to the computer, typified the cryptic way he spoke of himself.

On top of this, there was a matter that no-one wished to know about.

Turing was arrested on 7 February 1952 for his affair with a young Manchester man.

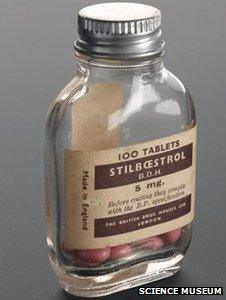

He was obliged to undertake injections of female hormones intended to render him asexual.

Until the 1970s, this was thought utterly unprintable and circulated only in academic gossip.

Even if unconsciously, this meant a black cloud hung over his scientific reputation.

In 1973, the Gay Liberation Front broke this silence, publishing a brief statement of what had happened as an example of what gay men had endured from the law and medicine, but few then were interested and his name meant little.

Unashamed

Turing was injected with Stilboestrol - a synthesised form of oestrogen

In this era, most people who heard on the grapevine of this story probably assumed that his death typified the suicide culturally expected of ashamed and exposed homosexuals.

In fact, his death came more than two years after the arrest. And he had shown defiance rather than shame.

He told the police that he thought there was "a Royal Commission sitting to legalise it".

In 1952 and again in 1953 he insisted on holidays abroad, in Norway and Greece, explicitly for freedom from British law, and very likely influenced by hearing of the early Scandinavian gay movement. His ears pricked up at a hint of modernity.

But as a gay man, Turing was particularly unlucky. The point in about 1948 when he decided to have a more positive gay life was just the point when there was a change from silence to active persecution.

It was not only in timing that he was cursed: there was his very special status.

What none of his friends knew in 1954 was that he had been the chief scientific figure in the codebreaking operation throughout World War II.

After 1948 the Cold War, the concept of security vetting and the needs of the American alliance ended the "one-of-our-chaps" basis on which he had been recruited in 1938.

After 1952, Turing had to stop the work he had continued to do for GCHQ, and what he cryptically referred to as a "crisis" in 1953 seems to have involved intense surveillance. It is for this very special and secret reason that his life in 1954 might well have seemed impossible to bear.

Merlin-like figure

Since the 1970s, everything has changed.

That homosexuality was criminal until 1967 has come to seem hardly credible, and the unmentionable has become commonplace.

The Bletchley Park codebreaking story, totally secret in 1954, became public after 1974, and Alan Turing emerged as a Merlin-like figure from this hitherto dark age, not only a genius of cryptographic theory but with hands-on responsibility for the U-boat war.

Nowadays the Bletchley Park Museum proudly puts him at the centre.

And now the computer is no longer a remote installation but an addictive hub of personal contact. As such it is much closer to the Turing concept of the universal machine, turned to any and every task, and always related to the power of the human mind.

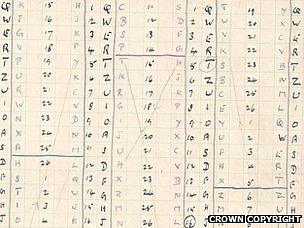

Turing's cryptology work at Bletchley Park helped counter the threat posed by Germany's U-boats

These changes, taken together, have made Turing much more accessible than he could ever have been in his lifetime. He has become, posthumously, a modern icon.

Alan Turing drank the cyanide but left an apple by his bed.

It was a grim joke against his reputation for impracticality, kindly allowing those who wanted to believe it that he had ingested the poison by mistake.

Turing himself knew the apple as an icon of death in the Snow White story, and perhaps his theatrical prop was also alluding to the great decision he made in 1938 to abandon the Eden of pure mathematics for the deadly business of duelling with Nazi Germany.

His story is tragic, but this last twist to his story is part of the comedy of life which, despite everything, he did his best to enjoy.

<italic>Andrew Hodges is a tutorial fellow in mathematics at Wadham College, University of Oxford, and author of Alan Turing: the enigma.</italic>

- Published18 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012