Alan Turing: The experiment that shaped artificial intelligence

- Published

Computer pioneer and artificial intelligence (AI) theorist Alan Turing would have been 100 years old this Saturday. To mark the anniversary the BBC has commissioned a series of essays. In this, the fourth article, his influence on AI research and the resulting controversy are explored.

Despite advances in computer technology, scientists have not been able to create a "thinking machine" that can pass the Turing Test

Alan Turing was clearly a man ahead of his time. In 1950, at the dawn of computing, he was already grappling with the question: "Can machines think?"

This was at a time when the first general purpose computers had only just been built.

The term artificial intelligence had not even been coined. John McCarthy would come up with the term in 1956, two years after Alan Turing's untimely death.

Yet his ideas proved both to have a profound influence over the new field of AI, and to cause a schism amongst its practitioners.

Knocking down naysayers

One of Turing's lasting legacies to AI, and not necessarily a good one, is his approach to the problem of thinking machines.

He wrote: "I have no very convincing arguments of a positive nature to support my views."

Instead, he turned the tables on those who might be sceptical about the idea of machines thinking, unleashing his formidable intellect on a range of possible objections, from religion to consciousness.

Turing outlined his AI experiment while working at the University of Manchester, where a memorial statue has since been erected

With so little known about where computing was heading at this time, the approach made sense. He asserted correctly that "conjectures are of great importance since they suggest useful lines of research".

But 62 years on, now that we have advanced computers to test, it seems wrong that some proponents of AI still demand the onus be put on sceptics to prove the idea of an intelligent machine impossible.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell ridiculed this type of situation, likening it to asking a sceptic to disprove there is a china teapot revolving around the sun while insisting the teapot is too small to be revealed.

This can be seen as wrong-footing the scientific process of hypothesis testing and evidence collection.

The Imitation Game

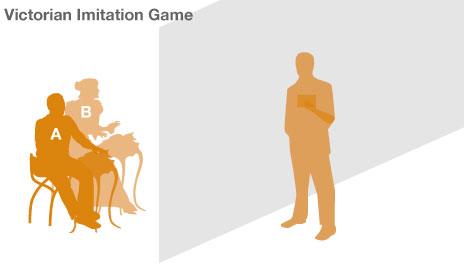

In fact, Turing well understood the need for empirical evidence, <link> <caption>proposing what has become known as the Turing Test</caption> <url href="http://loebner.net/Prizef/TuringArticle.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> to determine if a machine was capable of thinking. The test was an adaptation of a Victorian-style competition called the imitation game.

It involves secluding a man and woman from an interrogator who has to guess which is which by asking questions and studying written replies.

The man aims to fool the interrogator, while the woman tries to help him.

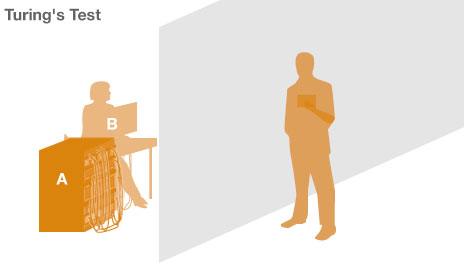

In the Turing Test, a computer program replaces the man. Turing asked: "Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman."

Effectively, the test studies whether the interrogator can determine which is computer and which is human (although Turing did not explicitly say that the interrogator should be told that one of the respondents was a computer it seems clear to me from his example questions that this was what he intended).

The idea was that if the questioner could not tell the difference between human and machine, the computer would be considered to be thinking.

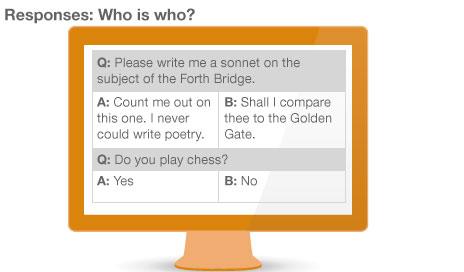

Turing was inspired by a parlour game in which an interrogator puts questions to a man and woman (A and B) in a separate room who reply with typewritten notes. The aim is to determine which is the man and which is the woman.

Turing's test replaces the man with a computer running a program designed to deceive the questioner about its true identity. Will he still be able to determine which is the woman?

The idea was that if the person asking the questions could not tell the difference between human and machine, the computer would be considered to be thinking and have artificial intelligence.

Failing the test

Turing suggested that by the year 2000 the average interrogator would have less than a 70% chance of making the right decision after five minutes of questioning.

My iPhone has more than 500 times the storage capacity he thought would be required and orders of magnitude more processing power, yet passing the test still seems a long way off.

In 1990, New York businessman Hugh Loebner set up the annual Loebner Prize competition with a prize of $100,000 (£63,500) to the creator of a machine that could pass the Turing Test.

Loebner Prize judges have five minutes to ask questions to determine which respondent is a computer and which a person

<itemMeta>news/technology-18475646</itemMeta>

The AI aristocracy strongly supported the contest until it became clear how badly the machines were performing.

Now in its twenty-second year, no machine has come even close to winning.

Marvin Minsky, one of the fathers of AI, wrote in 1995: "I do hope that someone will volunteer to violate this proscription so that Mr Loebner will indeed revoke his stupid prize, save himself some money, and spare us the horror of this obnoxious and unproductive annual publicity campaign."

No-one in AI seems to take the failure of the Turing Test as an argument against the possibility of thinking machines.

Because Turing had talked about a future "imaginable machine", some of the proponents say that we will have them at a future date. But others now argue that the Turing Test simply is not the best way to measure machine intelligence.

AI moves on

Despite the failure of machines to deceive us into believing they are human, Turing would be excited by the remarkable progress of AI.

It is flourishing in so many spheres of activity, from robots investigating the progress of climate change to computers running the world's finances.

I expect that Turing would have danced for joy in 1997 when Deep Blue defeated world champion Gary Kasparov at chess.

IBM's Watson beat two Jeopardy champions in a special edition of game show in 2011

I can also imagine him cheering in the wings of the TV game show Jeopardy when the program Watson beat the two best human opponents in the history of the American game.

It is difficult to tell how any of these achievements would have been possible without the continued inspiration from Turing's original and radical ideas.

In my opinion, the Turing Test remains a useful way to chart the progress of AI and I believe that humans will be discussing it for centuries to come.

<italic>Noel Sharkey is professor of artificial intelligence and robotics at the University of Sheffield and co-founder of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control.</italic>

- Published18 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012