Alan Turing: A multitude of lives in fiction

- Published

Turing's life has provided rich pickings for authors who have taken very different approaches to the material

If Alan Turing had not existed, would we have had to invent him? The question seems to answer itself: Alan Turing very much did exist, and yet we have persisted in inventing him still.

Of all the roles Turing played during his all-too-brief life, there is one he played only after his all-too-early death - that of fictional character.

Since Turing's suicide in 1954, his legend has been the inspiration for plays, novels, and films, in addition to a half-dozen biographies.

Andrew Hodges' late 1970s and early 1980s research into Turing's life, and the top secret work he did at Bletchley Park, burst open a groundswell of interest in a man whose story seems almost too tragic, and too poignant, to be true.

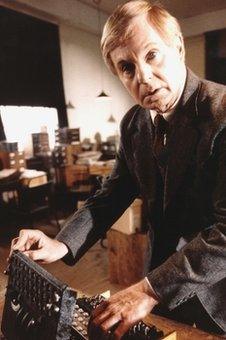

Derek Jacobi portrayed Turing in the BBC film Breaking the Code

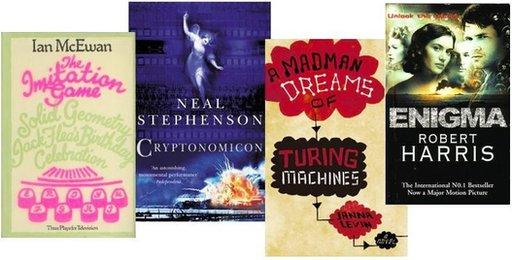

No less than Ian McEwan, Robert Harris, Tom Stoppard, Neal Stephenson, Janna Levin, and Hugh Whitemore have each written historical fiction centred around Turing in one form or another.

Imagine my quaking with terror as I had to follow such an intimidating list when I began work on my own screenplay about Alan Turing. How does one add one's quiet voice to such a beautiful chorus?

It begs the question: Why the enduring fascination with Turing, not only as historical figure, but as a literary one?

Perhaps because with a life as varied as Turing's, and with a body of highly technical work that yet seems always to reflect and illuminate his most personal struggles, he is simply too good a character to make up.

'Misunderstood hero'

The best-known fictional take on Turing is likely Hugh Whitemore's brilliant 1986 play Breaking the Code, which starred Derek Jacobi both in the West End and on Broadway before it was filmed for the BBC.

Whitemore presents a historically accurate picture of Turing: Awkward, stuttering, unashamed of his sexuality and endlessly immersed in his intellectual obsessions.

This is Turing as misunderstood hero, brought to the level of grand tragedy. Whitemore connects Turing's AI work to his closeted homosexuality by suggesting that the latter gave him some manner of insight into the former.

An innocent and a consummate outsider, Turing saw neither the sexual strictures of his time nor its mathematical ones as being particularly sound. His disregard of one made him a hero, the other a criminal. The play was nominated for three Tony awards.

Conversely, Neal Stephenson's epically witty 1999 novel Cryptonomicon, which in its 900+ pages employs Turing as a prominent side character, takes a tonally opposite approach - allied cryptology as grand fun and games.

Stephenson uses historical fiction's ability to conjure hypothetical, counterfactual realities to play a great game of "what if" with the Turing legend.

What if Turing had in fact been having a secret love affair with the head of German cryptographic operations? What if the two had been sending each other romantic notes back and forth across the battle lines, using their respective cryptographic teams to do so?

It's a grand romp. There are pirates. Treasure is sunken, and then eventually discovered. And the story of Alan Turing becomes, of all things, a delight.

Oscar winning screenwriter, Tom Stoppard, is among those to have tackled Turing

Breaking the code

Janna Levin's masterful novel A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines, published in 2007 compares Turing and his forbearer Kurt Godel via intertwining psychological sketches.

Both are concerned with whether or not it's possible to know by looking at a problem if it might eventually have a solution - and how do you know you've found the solution to a problem at all. The history of computing would never be the same.

In Ian McEwan's short BBC play The Imitation Game, from 1980, we don't ever actually get the pleasure of meeting Alan Turing. Instead, we follow a young recruit to the Women's Royal Navy in 1940 as she meets, and courts, a brilliant cryptographer named Tanner.

In an essay that accompanied the play's publication, McEwan said that he'd started out trying to write a play about Turing, but then abandoned it for an entirely fictional tale.

What seems to interest McEwan most is not the mathematics or the military history, but rather the social environment of men and women working side-by-side for the first time in their lives. And in the misunderstandings that necessarily arise when young people are forced to confront and discuss sex, a topic for which they lack the language to communicate.

It's a theme McEwan returned to frequently in his career and it's a theme that resonates deeply with the real Turing, a man who struggled with the available language to describe his own sexuality.

Ian McEwan campaigned for an official pardon for Turing after writing a play about him

The legacy lives on

And finally, Robert Harris's 1995 novel Enigma and the 2001 film adaptation written by Tom Stoppard perform a similar trick: We are presented with a story about the codebreakers of Bletchley Park, and yet Alan Turing is not among them.

Instead, the story of the breaking of the German Enigma machine is placed in the hands of a mentally unstable, lovelorn mathematician. In the novel, Tom Jericho is a student of Turing's at Cambridge, while in the film Turing is altogether absent.

Though clearly inspired by Turing, Jericho is straight, and in fact the love triangle in which he finds himself ends up changing the course of the war.

In a sense, we find here an imagined version of Turing's real-life relationship with his fellow codebreaker Joan Clarke, to whom Turing was briefly engaged in 1941: Two mathematicians in love during wartime, the fate of the Allies in their hands.

In response to such a wonderful variety of fictionalised Turings, I will hope only for this: that as Turing's legacy lives on, so should his legend.

The first gave us the phones in our hands and the computers on our laps, the second gave us the books and films we view on both.

Let a million Turings bloom.

<italic>Graham Moore's screenplay The Imitation Game topped the 2011 Black List of best unproduced screenplays in Hollywood. Warner Bros picked up the film and plans to release it in 2013.</italic>

- Published18 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012

- Published21 June 2012

- Published23 June 2012

- Published23 June 2012

- Published20 June 2012