Lost picture inspires Colossus reunion

- Published

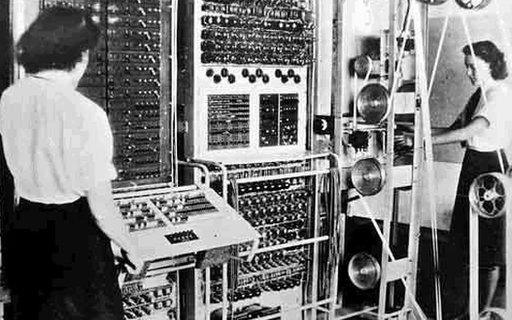

The reunion meeting stirred memories of the hours spent at Bletchley tending Colossus

A rediscovered photograph from World War Two has reunited some of the women who worked on the Colossus code-cracking computer.

The photo of the 39 women of Colossus C Watch was unearthed for the first time since the War by Joanna Chorley.

The picture enjoyed wide publicity during celebrations for the 70th anniversary of Colossus.

Many of those pictured contacted the museum where Colossus currently resides which then reunited some of them.

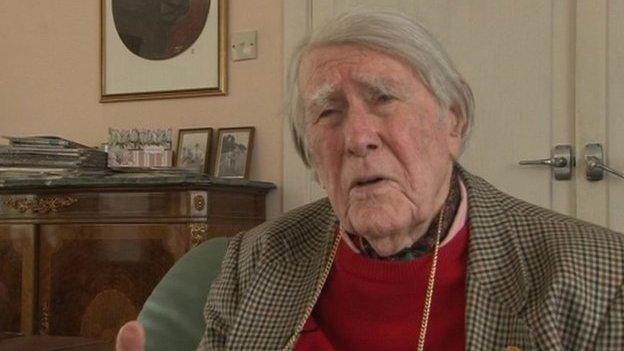

Recently six of the women seen in the photo were brought together to reminisce and rekindle former friendships. Maggie Mortimer, Joanna Chorley, Lorna Cockayne, Betty Warwick, Margaret O'Connell and Margaret Kelly all attended the reunion meeting at the National Museum of Computing.

Ms Chorley said she had found the picture among documents and papers stored in an old bureau, where it had lain forgotten for decades.

"I know nothing about it," Ms Chorley told the BBC at the reunion. "It's an absolute mystery. I do now remember that we were all given one but that's all I do recall."

During the War, Ms Chorley was part of the Women's Royal Naval Service (Wrens), and many of its recruits were picked to work at Bletchley and operate the code-cracking machines developed there.

The Wrens that worked on Colossus had to be above a certain height to ensure they could reach all the parts of the massive machine, and they had to have attained certain school qualifications. Prior to being sent to Bletchley, all the women underwent interviews that also tested their aptitude for maths and logic.

War work

"There were only two Colossus machines when we got there," said Margaret Mortimer, adding that more were added as the War went on. Wrens had tended to be assigned to one machine and stuck with it as they had got to know its foibles, she said.

Ms Mortimer does not have fond memories of her time working with Colossus.

"We worked terribly long hours in not terribly pleasant working surroundings," she said. "We stood up all the time to operate the machine, so it was terribly tiring."

"Bletchley Park during the War was pretty miserable," said Betty Warwick. "We worked jolly hard. It was eight-hour shifts and then we had to fill in for anyone that was not there."

"We were billetted at Woburn Abbey, where the food was awful," she said. "Bad eggs and fish with maggots in it."

Women from the Royal Navy reserves were recruited to work on Colossus

"It was not very stimulating work," said Betty O'Connell, who worked on Colossus 1 for most of her time at Bletchley. She added that socialising was difficult because Woburn Abbey was about 10 miles away from Bletchley and they travelled between the two sites by bus.

"When we were there it was like being in another closed world," she said. "We were rather isolated. It was a bit like being at boarding school because, like there, you didn't talk about your business at all."

But some of the Wrens who worked on Colossus did enjoy their time with the pioneering computer.

"I had a love affair with Colossus because it was such a clever machine," said Ms Chorley. "I wanted to know as much about it as possible."

Lorna Cockayne was similarly entranced by what the machine was doing.

"I can still see the table covered in small round rolls of tape that we were given to load up," she said, adding that to this day she can remember the order of the keys on the teleprinter attached to the machine.

Ms Cockayne was also in no doubt about the codes they were helping to break.

"There was no question about getting us to do something we didn't understand," she said. "We knew these were important messages from different fronts."

Despite their different experiences with operating Colossus, all were agreed on the importance of keeping it secret.

"I was pretty horrified when details of Colossus started to be made public in the 70s," said Ms Warwick. "At the time we were so pressured never to say anything to anyone about it. We kept the secret for such a long time."

- Published5 May 2014

- Published7 February 2014

- Published26 March 2014

- Published6 February 2014