Hi-tech cars are security risk, warn researchers

- Published

Security researchers are worried that car computer systems could make them vulnerable to hackers

The most complicated computational device you own is probably not in your pocket, not mining bitcoins in the back room or nestled by the TV helping the kids "frag" their friends in eye-popping video game HD.

It might be sitting on your drive, in the garage or on the street.

The it, in this case, is your car.

Modern vehicles are very smart. They can recognise that they are crashing faster than you can and prepare for the impact before you have time to think: "This is going to hurt."

They know when it is raining, when you are straying from your lane or are in danger of hitting the wall when you park.

"Cars today are not just computers on wheels," says security researcher Josh Corman.

"They are networks of computers on wheels."

And therein lies the problem, he tells the BBC.

Mr Corman is spokesman for a grassroots group known as I Am The Cavalry (IATC) that seeks to communicate the thoughts and fears of many professional security testers to the wider world. Of late, IATC has been getting very worried about cars.

Early attempts at hacking vehicles involved taking them apart to access their systems

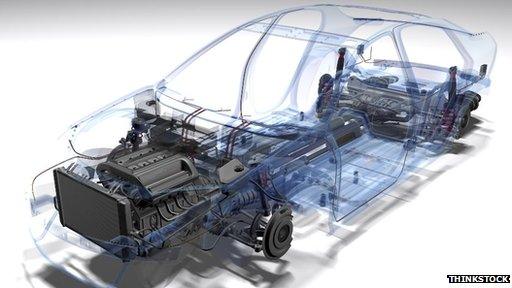

A modern car, Mr Corman says, has up to 200 small embedded computers in it, known as electronic control units (ECUs), each one of which, in general, oversees one subsystem.

They all connect to a network that ships data around the car to co-ordinate what is going on as it is driven.

The embedded computers are typically not made by car manufacturers. Instead they come from other companies, which often do not - or will not - say how they work.

Physical hacks

Before now, that has not worried the carmakers who just want the black box to meet their specifications for such things as monitoring tyre pressure, measuring the angle of the steering wheel, working out how many people are in the car or that they are wearing seatbelts.

But the lack of transparency has vexed security researchers who, in recent months, have been taking a much closer look at in-car computer systems.

They have not been impressed by what they have found.

Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek of security firm IOActive led the way in hacking the computer systems in cars, says Andy Davis, head of research at NCC Group.

The early work on car hacking involved getting physical access to the vehicle.

Vehicles often contain computer-controlled parts made by several different manufacturers

Mr Miller and Mr Valasek literally tore apart the cars they investigated to get at the Controller Area Network (Can) buried in its substructure.

"If you can get access to that Can either physically or remotely you can essentially control the vehicle," says Mr Davis.

At the recent Def Con hacker conference in Las Vegas, the two IOActive researchers presented their latest work entitled, A survey of remote automotive attack surfaces.

It took a close look at the hackability of 21 separate vehicles. Everything from a Toyota Prius to a Range Rover Evoque.

The report found exploitable problems almost everywhere it looked - in wireless tyre pressure sensors, telematics controllers and even anti-theft systems.

A study indicated the 2014 Jeep Cherokee was more vulnerable than several rival models

The 2014 Jeep Cherokee topped the list of the most hackable cars and the 2014 Dodge Viper was the least hackable.

But the Jeep's maker, Chrysler noted that there had been "been no documented, real-world incidents of remote hacking".

"We have a team of engineers dedicated to developing cyber-security features in anticipation of emerging threats," it added.

"Further, Chrysler Group strongly supports the responsible disclosure protocol for addressing cybersecurity. Accordingly, we invite security specialists to first share with us their findings so we might achieve a cooperative resolution. To do otherwise would benefit only those with malicious intent."

Breakdown alerts

Many of the latest attacks seek to get at a car remotely via the communication systems now sported by many modern vehicles, explains Mr Davis.

"The reason this has become much more of a high-profile, ongoing issue is because of the way things are going in the car industry and the whole idea of the connected car."

In Europe and the US there are moves to set up so-called eCall systems that automatically contact emergency services when a vehicle has been involved in a serious accident.

An allied bCall system would ring for help in the event of a breakdown.

There is no doubt, says Mr Davis, that soon all cars will be connected cars.

There are plans for cars to be able to call for help in the event of a breakdown

"That has made all the carmakers realise it's something they need to provide," he adds.

"But if they have to do this we have to ask what else can we do to it?"

Black box

NCC Group recently conducted a six-week investigation into the security of vehicles from one manufacturer, which it declined to name.

Mr Davis says a whole range of security problems was found, but the biggest failing in his mind only emerged when researchers questioned the carmaker about issues that had arisen during the tear-down.

"We let them know about our assumptions of how the ECUs could be abused and they said, 'This is a black box for us,'" Mr Davis recalls.

"So, they went to the third-party that made it, who said it was proprietary information and we will not tell you."

Mini-computers can spot potential problems at an early stage

That's a big problem, he adds, because it means solving those security issues becomes much more difficult.

This lack of clarity about the innards of in-car computers prompted IATC to publish a letter calling on vehicle makers to improve security.

Some steps have already been taken, says Mr Corman, thanks to IOActive raising the issue in the media.

That's led to it being discussed more inside car firms and, in particular, among R&D and engineering staff.

"They know what they need to do but they have been lacking the executive support to make it happen," he says.

He singles out Tesla as one carmaker that is setting good standards. It has an open disclosure policy and actively seeks help to squash bugs in the software and other systems used to control its cars.

Researchers say the car companies are becoming more aware of the risk of hackers

But he acknowledges that it will take time to encourage others to do likewise and demand more open and secure standards from their suppliers, Mr Corman adds.

"We're taking a strategic long view," he says.

"It has to be a long view given how long it takes to do R&D, how long it takes to do testing and to bring a car to market.

"This is not like Facebook where if there is a security problem they can fix it overnight."

- Published26 August 2014

- Published18 August 2014

- Published11 August 2014