Moore's Law: Beyond the first law of computing

- Published

Gordon Moore says he had not expected his "law" to hold true for so long

Computer chips are arguably both the most complex things ever mass produced by humans and the most disruptive to our lives.

So it's remarkable that the extraordinary pace they have evolved at was in large part influenced by a three-page article published 50 years ago this weekend.

It noted that the maximum number of components that manufacturers could "cram", external onto a sliver of silicon - before which the rising risk of failure made it uneconomic to add more - was doubling at a regular pace.

Its author, Gordon Moore, suggested this could be extrapolated to forecast the rate at which more complicated chips could be built at affordable costs.

The insight - later referred to as Moore's Law - became the bedrock for the computer processor industry, giving engineers and their managers a target to hit.

Intel - the firm Mr Moore went on to co-found - says the law will have an even more dramatic impact on the next 20 years than the last five decades put together.

But could its time be more limited?

Industry driver

Although dubbed a "law", computing's pace of change has been driven by human ingenuity rather than any fixed rule of physics.

"Moore's observation" would be a more accurate, if less dramatic, term.

In fact, the rule itself has changed over time.

Mr Moore's article contained this cartoon, predicting a time when computers would be sold alongside other consumer goods

While Moore's 1965 paper talked of the number of "elements" on a circuit doubling every year, he later revised this a couple of times, ultimately stating that the number of transistors in a chip would double approximately every 24 months.

"In the beginning, it was just a way of chronicling the progress," he reflects.

"But gradually, it became something that the various industry participants recognised as something they had to stay on or fall behind technologically.

"So it went from a way of measuring what had happened to something that was kind of driving the industry."

Exponential explained

For most people, imagining exponential growth - in which something rapidly increases at a set rate in proportion to its size, for example doubles every time - is much harder than linear growth - in which the same amount is repeatedly added.

To illustrate an example of exponential growth that follows a similar course to Moore's law, imagine that as part of an exercise regime Mary swims the length of a 22m (72ft) pool, the size found in many hotels.

Every two years, Mary doubles her distance, and she is committed to repeating this over the course of 50 years.

So, after two years her regime consists of 44m.

At first, the increasing rate of growth may not seem overly impressive. After 10 years, Mary is swimming 704m - or 32 lengths.

That is nearly the equivalent of travelling the length of a football pitch seven times.

But the two-yearly doubling effect does not take long to dazzle. By 26 years - about half-way into her workout scheme - she would have to travel 180km.

That is the equivalent of swimming five and a half times across the English Channel at its narrowest point or once across the Taiwan Strait, which separates the island from mainland China.

By the time Mary reached 50 years, she would have to swim 738,198km.

That is the equivalent of travelling all the way from the Earth to the Moon and back again, at least for much of our satellite's orbit. Phew!

Moore retired in 1997, but Intel still follows his lead.

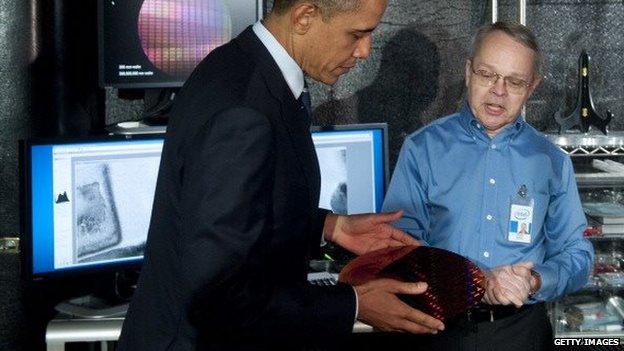

"Having Moore's Law as a guide - or as some of us have said, as our guiding north star - has kept us on pace, both in terms of how far we should scale and when we should scale," Mark Bohr, Intel's director of process architecture and integration, tells the BBC.

"Without [it] I think we'd be many generations behind in terms of technology.

"Instead of having all the computing power of a smartphone in your hand today, we'd still be using desktop computers from 10 to 15 years ago."

Mr Bohr acknowledges, however, that progress comes at a price.

Mr Bohr showed a whole silicon wafer before it was cut into parts to President Obama in 2011

Intel has had to spend ever increasing amounts on research and its manufacturing plants to stay on target.

And some question how long it can maintain this trick.

In 2013, the firm's ex-chief architect Bob Colwell made headlines when he predicted Moore's Law would be "dead" by 2022 at the latest.

The issue, he explained, was that it was difficult to shrink transistors beyond a certain point, external.

Specifically, he said it would be impossible to justify the costs required to reduce the length of a transistor part, known as its gate, to less than 5nm (1nm = one billionth of a metre).

"The amount of effort it's going to take to do anything beyond that is substantial," he said.

"We will play all the little tricks that we still didn't get around to, we'll make better machines for a while, but you can't fix [the loss of] that exponential. A bunch of incremental tweaks isn't going to hack it."

What is a transistor?

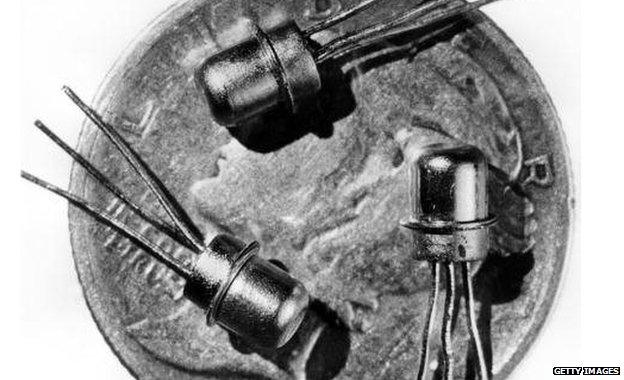

Early transistors were big enough to be individually picked up by hand

In simple terms, a transistor is a kind of tiny switch that is triggered by an electrical signal.

By turning them on and off at high speeds, computers are able to amplify and switch electronic signals and electrical power, making it possible for them to carry out the calculations needed to run software.

The first transistor - invented in 1947 - was roughly 2.5cm (1in) across.

You can now fit billions into the same space.

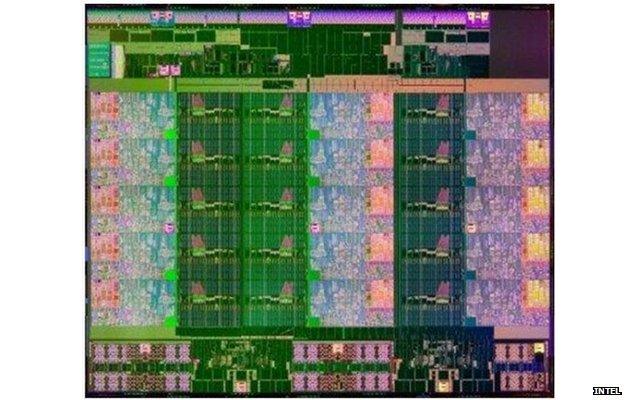

There are more than four billion transistors in Intel's 15-core Xeon E7 v2 chip

Intel has yet to reveal how it intends to overcome the challenge, but Mr Bohr insists progress is being made.

"Over the past 30 years there has been a long string of industry experts who have predicted the end of Moore's Law within five to 10 years," he says.

"Although I have a lot of respect for Bob Colwell, I think he's wrong."

Forthcoming advances in computing power will dwarf previous achievements, Mr Bohr adds, with the consequence that processors will "disappear" into our clothes, accessories and wider surroundings.

Mix of parts

British firm ARM - whose rival chip designs are used by Samsung, Apple and many others - agrees that ever smaller transistors should continue to deliver benefits for many years.

But it highlights that in the mobile age, things have moved beyond simply trying to offer more processing power at a reasonable price.

The focus now, it says, is to add functions to tablets and smartphones - such as slow-mo video capture and faster downloads - while ensuring that their batteries are not over-taxed.

Most smartphones and wearable tech is powered by ARM-based chips rather than Intel's tech

"What's important is if you are changing experiences, it's not just about am I providing more compute capability," explains marketing chief Laurence Bryant.

"What appeals to consumers is great battery life and thin devices."

This is why there has been a recent trend towards "multi-core" processors.

These squeeze in more transistors to support complex tasks, but keep many of them powered down much of the time in order to extend battery life.

Aided by algorithms

Even if processors do stop being improved as quickly as we've become accustomed to, computing itself could continue to leap forward.

"It's not quite irrelevant whether the density of transistors per chip continues to increase at the same exponential rate for the next 50 years - it would be great it it did - but our future and progress with all things digital does not depend on that very much," comments Andrew McAfee, cofounder of MIT's initiative on the digital economy.

"It depends more on getting tools out there to more people and improving our approaches with software and algorithms."

Experts says advances in some types of software are already outpacing processor speed gains

He says he frequently speaks to developers who report code-based advances that make Moore's Law look "ridiculous in comparison".

But he acknowledges that that the software industry would benefit from its own equivalent to the rule.

"When we talk to our friends working at the cutting edge of software systems that do artificial intelligence they say: 'Look this terrain is shifting so quickly that we don't even have a rough rule of thumb or a heuristic to use to see where we should be in 12 months, we keep getting surprised."

Household name

It's technology's job to supersede the old and leave it on the scrapheap.

Gordon Moore was 36 years old when he penned his influential paper for Electronics magazine

So, it's only fitting that this fate will befall Moore's Law, whether it is now or in the decades to come.

Whatever the date, it's indisputable that its creator has left his mark on computing's early years.

"It's amazing how often I run across a reference to Moore's Law," the 86-year-old remarks.

"In fact, I Googled Moore's Law and I Googled Murphy's Law.

"Moore beats Murphy by at least two to one."

- Published8 April 2015

- Published5 September 2014

- Published23 April 2012