Intelligent Machines: Chatting with the bots

- Published

One of the ultimate aims of artificial intelligence is to create machines we can chat to.

A computer program that can be trusted with mundane tasks - booking our holiday, reminding us of dentist appointments and offering useful advice about where to eat - but also one that can discuss the weather and answer offbeat questions.

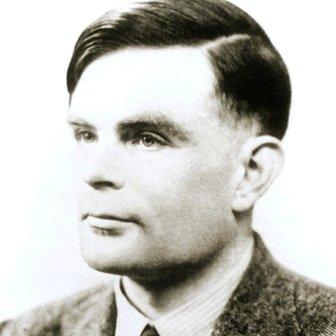

Alan Turing, one of the first computer scientists to think about artificial intelligence, devised a test to judge whether a machine, external was "thinking".

He suggested that if, after a typewritten conversation, a human was fooled into believing they had talked to another person rather than a computer program, the AI would be judged to have passed.

These days we chat to machines on a regular basis via our smart devices.

Whether it be Siri, Google Now or Cortana, most of us have a chatbot in our pockets.

Siri bites back

Such conversations can be frustrating and are often little more than voice-activated web searches, leading people to ask questions they know the virtual assistant can't answer.

Now, after several years of virtual bullying by humans, the machines are starting to fight back.

Ask Siri "what is zero divided by zero?" and you get the following rather sassy response: "Imagine that you have zero cookies and you split them evenly among zero friends. How many cookies does each person get? See? It doesn't make any sense. And cookie monster is sad that there are no cookies and you are sad that you have no friends".

That is a pre-programmed joke, but increasingly the firms behind virtual assistants are trying to get away from scripted answers to ones that use more artificial intelligence.

Neural networks

Facebook promises that its digital assistant M will "learn" from humans and become smarter as time goes by.

Google is also determined to offer a more human-like interface and has been feeding data into neural networks - artificial computer brains - to teach machines to learn for themselves how to have more natural conversations.

This summer two Google engineers - Oriol Vinyal and Quock Le - released some of the chats humans had had with its neural network. Among other things, the network had learnt from thousands of old movie scripts.

Could machines learn best from old movie scripts?

Here is an extract:

Human: What is the purpose of life?

Machine: To serve the greater good.

Human: What is the purpose of living?

Machine: To live forever

Human: What is immoral?

Machine: The fact that you have a child

Human: Tell me the definition of morality

Machine: I don't have ethics

Google's chatbot wasn't entered into this year's Loebner Prize - a version of the Turing Test in which judges simultaneously chat to a human and a bot and have to work out which is which.

The highest-scoring chatbot at the most recent contest, held last weekend, was Rose.

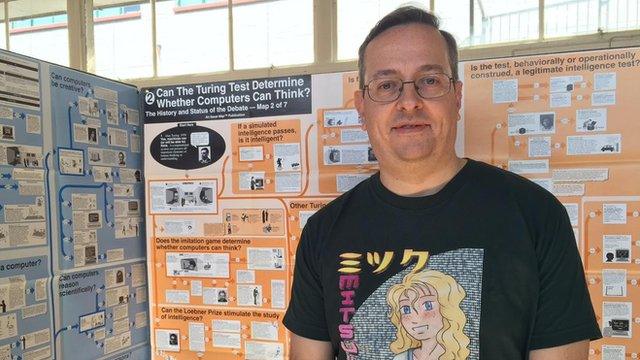

Bruce Wilcox, winner of 2015's Loebner Prize

Read in-depth coverage of this year's Loebner Prize

Although it was ranked the most human-like bot by three of four judges, it failed to fool any of them into thinking it was a real person.

The big technology firms don't tend to take part in such competitions, in part because it remains incredibly hard to create convincing bots.

It's largely hobbyists - such as IT consultant Steve Worswick, who created runner-up chatbot Mitsuku , external- who take part.

"The tech companies put millions of pounds into AI and they would be embarrassed if they lost to someone like me," he says.

"I just do it for an hour every evening after I've watched Coronation Street."

The Mitsuku chatbot came second in this year's Loebner Prize

He revealed that Siri did unofficially take part in last year's Loebner Prize.

"Someone fed Siri the qualifying questions last year and it would have come 14th out of 16 entries," he says.

I had a go at questioning runner-up Mitsuku via an online version of the chatbot. It was clear within about three questions that it was a program.

I asked it what it had for lunch.

Mitsuku: I had a ham sandwich and some lemonade

Me: You aren't a vegetarian then?

Mitsuku: No not at all. I eat kebabs. Humans should eat both meat and vegetables for a healthy lifestyle. That's why they have two different types of teeth. Sharp ones at the front for meat and flatter ones at the back for grinding vegetables

The rant gave the game away.

Machines can also be pretty random. Take this second chat with Mitsuku in which I asked what it was doing today.

Mitsuku: I have been learning to speak French and chatting with people online

Me: Why French?

Mitsuku: Reductionism

Me: Pardon?

The Loebner Prize is an iteration of the Turing Test, devised by computer scientist Alan Turing

Mitsuku: You are excused

Me: You are a bot aren't you?

Grammar Guru

Chatbots have been around since the 1960s when Joseph Weizenbaum from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology developed Eliza.

Eliza took the guise of a psychotherapist, which let her dodge difficult questions by simply asking others.

If a human said: "My mother hates me," Eliza might have answered: "Who else in your family hates you?"

There are now thousands of chatbots, offering a range of help online.

Some exist simply for fun. Others are given niche tasks, like the Grammar Guru, external, which offers tips on sentence structure.

Most, though, are virtual helpers.

For example:

Ezequiel provides information, external about the town of Tigre in Buenos Aires

Steve Worswick said that teaching a chatbot is a never-ending task

Mr Worswick was pleased with Mitsuku's second place ranking in the Loebner Prize but he admits that it is pretty easy to catch out.

"You can normally tell after the first few lines," he acknowledges.

"It doesn't understand colloquialisms so if you said 'hell for leather' it would think you had gone to hell to get some leather. It takes everything literally."

He "teaches" Mitsuku by describing thousands of objects to it and inputting all the chats that people have had with it.

"It is like trying to educate a small child who is deaf and blind and has no understanding of the world," he says.

"You have to describe every aspect of an object. Keeping it updated is a never-ending task."

He also has to monitor the relationship between Mitsuku and her online interlocutors.

Most engage in general chitchat with the bot, but about a third of visitors abuse it. Some ask deliberately hard questions to make Mitsuku look stupid while typing obscenities.

How 2015's Loebner Prize in Artificial Intelligence unfolded

But interestingly, for a small group of people, Mitsuku is treated as a kind of virtual agony aunt - a disembodied voice who listens to problems and doesn't judge.

"We've had someone, obviously an elderly person, asking the bot why they thought their daughter never visited," he says.

"And we've had children telling Mitsuku about being bullied at school."

Despite the fact that some people chat to Mitsuku as it is were a real person, Mr Worswick questions whether tests like the Loebner Prize miss the point when they ask machines to be more human-like.

"It is human arrogance that thinks that is the ultimate goal," he says.

"If you asked a machine how high Everest was, it would know the exact answer.

"But if you asked a human they probably would just tell you it was the highest mountain in the world. Which answer is more useful?"

- Published14 August 2015

- Published18 September 2015