Tech eases Syrians' trauma in Jordanian refugee camp

- Published

Safwan Harb created an electric bike from spare parts that he found

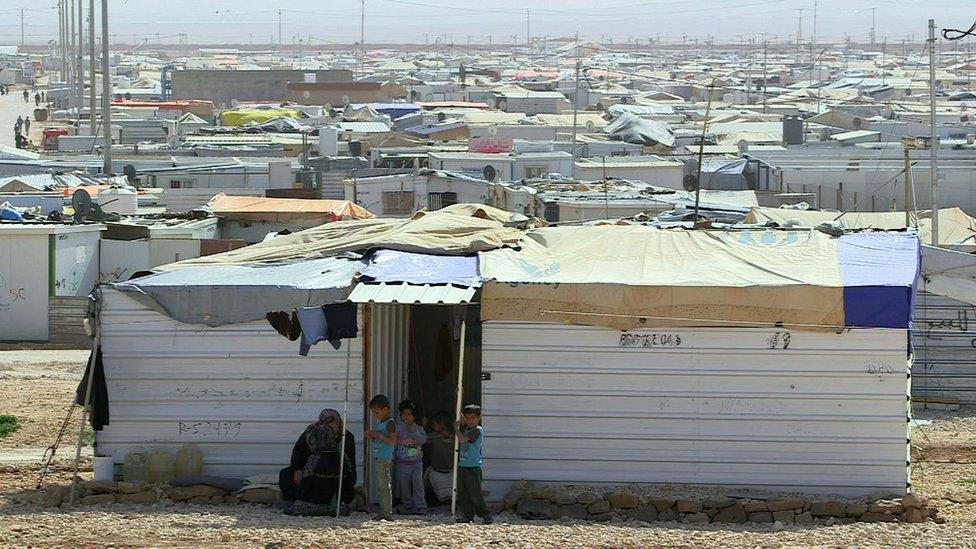

The thousands of dusty shops and houses do not at first seem like a place where technology would thrive.

But the Zaatari refugee camp near the Syrian border in Jordan houses a vibrant community of makers.

The majority of the residents are from the Syrian city of Daraa, commonly called the cradle of the revolution for the role it played in early anti-government protests.

The camp was formed four years ago when people fled the war across the border. Now, more than 80,000 people are estimated to live in Zaatari.

Despite the incredible hardships many have faced, there is a vibrant entrepreneurial spirit here.

The Zaatari refugee camp has been described as being Jordan's fourth largest city

The camp's main street is called Sham Elysees. It's a play on ash-Sham - a word Syrians call Damascus - and the famous Parisian boulevard, Champs Elysees. Hundreds of shops line the street, covering everything from wedding dresses to mobile phone repair shops.

It's here we meet disabled inventor Sawfan Harb who has lived in Zaatari for three years. He fled Syria with two family members, who are also disabled.

Sawfan found it difficult living in the camp when he first arrived as many roads were not paved and he didn't want to rely on people to push or carry him in his wheelchair.

He discussed with his brother the possibility of creating an electric bike out of spare parts in the camp. With the help of a local welder his plans were brought to life.

"Because of my disability I'm forced to be creative and find ways to help me live my life as easily as possible, be it in Syria or here, it's the same," he says.

"People were at first surprised to see such a bike in the camp. They've never seen anything like it before. Some liked it, others were just surprised."

Sawfan Harb's bicycle is powered by batteries stored in a basket at its front

Of course, there are many barriers to refugees living in the camp accessing technology. Electricity is only on for half the day in the camp and money is in short supply.

Safwan would like to enhance his technical skills with academic courses.

"If possible I would like to study technology because I have ideas but I need academic learning," he says.

"I have other ideas but I have no support, even a simple idea needs a certain amount of money."

Biometric checks

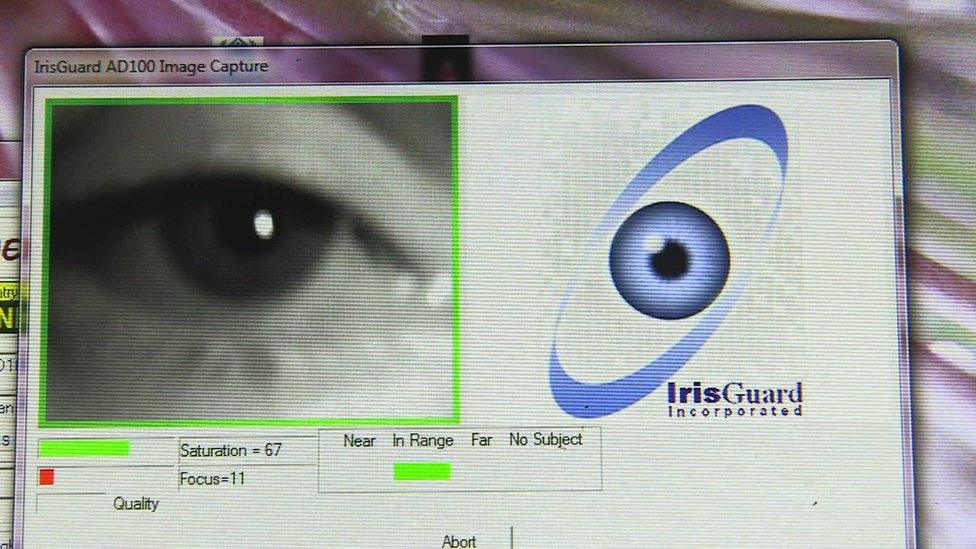

Syrians refugees living outside the camps can withdraw money from banks by providing eye scans

Syrian refugees entering Jordan have their irises scanned by the UNHCR (UN High Commissioner for Refugees) using IrisGuard technology.

This biometric data is collected to confirm identities but also provides services from local partners to help make life a bit more normal for refugees. This includes the Cairo Amman Bank, which is linked to the biometric database and sets up an account automatically for each family.

A nominated family member can take aid money out in the blink of an eye at bank machines. There is no need to register information again with the bank as it comes through the UNHCR's secure EyeCloud server based in Amman.

Eye scans are used to take a record of refugees' identities when they enter Jordan

The data is also shared between four countries: Egypt, Jordan Lebanon and Iraq, to ensure people aren't registered in two countries at the same time.

More refugees live in Jordan's capital Amman than in refugee camps. Finding ways to integrate them into Jordanian society and provide access to technology is the focus of a group of companies and philanthropists called Refugee OpenWare.

Its focus is on how to deploy advanced technologies to improve human rights in conflict zones and host communities for refugees.

In a modern office park full of start-ups is 3Dmena, a core member of the group which mainly works on fabrication technologies, including 3D printing.

One of the Ultimaker 3D printers was used to make a prosthetic hand for this Yemeni child

A row of Ultimaker printers lines one wall of its office; a machine the company is trying to convert to 3D-print food sits in the corner.

"We focus on advanced technologies like 3D printing, internet-of-things, robotics, virtual reality and how we engage physical and traditional industries in digital fabrication," says 3Dmena's co-founder Loay Malahmeh.

Mr Malahmeh also reaches out to Syrian refugees to work at his company. Asem Hasna worked as a paramedic driving an ambulance in Syria.

He lost his left leg in a bomb explosion. He was working in a traditional prosthetic centre in Amman when he saw one of 3Dmena's 3D printers the team had brought to the hospital for a fitting.

Refugees have been given access to 3D printers via funds provided by a humanitarian aid group

Within three weeks Mr Hasna became proficient in 3D printing and hacked the printer to print in a material it hadn't been able to before. He even taught people from Jordan's Royal Rehabilitation Hospital how to use it. He became 3Dmena's technical director.

One of the devices Mr Hasna created was an echolocation device using haptic feedback. It buzzes the hand of a Syrian refugee who was blinded by a sniper, helping to alert him to objects in his way so he can walk more confidently.

The solutions they are printing are relatively inexpensive, which could help provide cheaper prosthetic solutions to people with little money. Mr Hasna's prosthetic foot needs a rubber element to be replaced twice a year which usually costs around $35 (£25).

But with the printer he could manufacture the part in a flexible material in under 30 minutes for just $1.50.

A 3D-printed scanner allows one blinded refugee, Ahmad, to be warned of obstacles in his path

Besides training refugees who are living in Amman, 3Dmena hopes to bring a fabrication lab with different computer controlled machines - including wood-working, metal workshops and 3D printers - directly to the refugee camp.

Mr Malahmeh hired a professor of conflict studies to do research in Zaatari over a period of two months, conducting more than 270 surveys and 65 focus groups.

More than 95% of respondents said they felt having a platform for 3D printing in Zaatari would have a big impact. More than 45% said they would use it at least three times a week to solve problems relating to shelter, transport, electricity, sanitation and food production systems.

But for now, 3Dmena is focused on setting up operations in Turkey and Gaza.

"Unfortunately we received a rejection letter due to a lot of security issues, so the project in Zaatari is on hold," says Mr Malahmeh.

"But hopefully, if we get approval, we can do it."

UK-based readers can watch Jen Copestake's full report from Zaatari on iPlayer.

- Published8 December 2015

- Published24 September 2014

- Published13 December 2013