How mobile tech is improving global disaster relief

- Published

An injured girl speaks to her mother via mobile after April's devastating earthquake in Nepal

When war or natural disaster causes havoc around the world and millions of people are displaced or rendered homeless, communications and power infrastructures are often damaged or non-existent.

Yet people are desperate to let their loved ones know they're safe and to find out what's going on.

"The first questions people always ask when they arrive at a refugee camp are 'Where can I charge my phone?' and 'Is there wi-fi?'," says John Warnes, innovation specialist at the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

"These often seem to be more important to people than food and water."

Administering food, shelter and medical aid is made even harder for aid agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) without proper communications.

Migrants are increasingly relying on smartphones for navigation and helpful information

So some technology companies have been innovating to find ways of meeting these challenges.

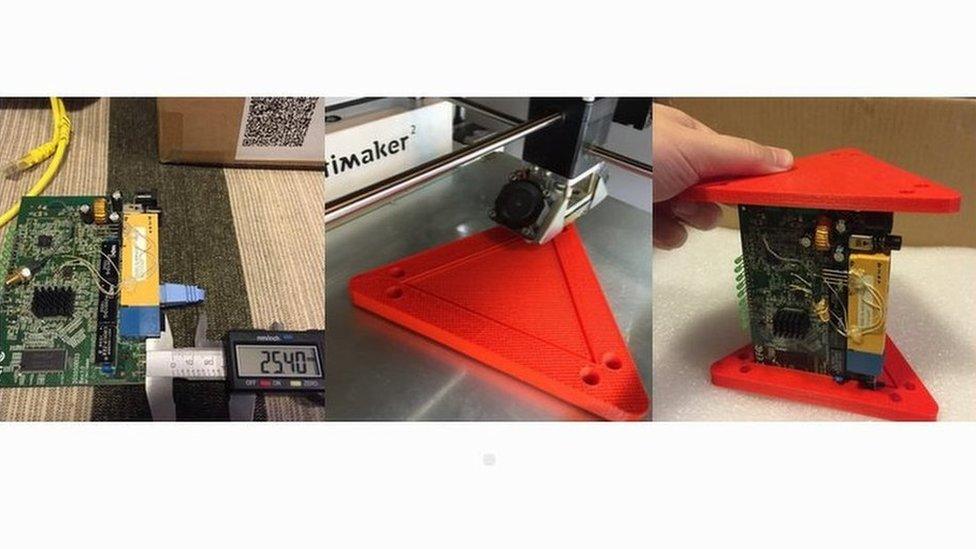

Instant hotspot

For example, Croatian firm MeshPoint has designed a highly-portable rugged, all-weather wi-fi and 4G mobile device that can connect up to 150 people to the internet at the same time. It contains a built-in battery to enable quick set-up in the most inhospitable conditions.

The unit can be used on its own to create a local internet hotspot, or linked to others to form a network for use over a wider area.

MeshPoint uses open source software so anyone can make the wi-fi hotspot

What started out as a battery-powered modem and wi-fi router in a backpack to provide connectivity to refugees in east Croatia, has developed into a potential business, says Valent Turkovic, one of MeshPoint's co-founders, speaking at the Techfugees conference, external in London.

He says the firm is trying to raise investment on crowdfunding site, Indiegogo, and envisages the units selling for around €400 (£287) each.

Mobile mobile

Telecoms companies have been engaging in larger-scale communications projects in disaster areas around the world, but are also realising the benefits of more portable solutions.

For example, Vodafone Foundation, the telecom giant's charitable arm, has developed "instant network mini", an 11kg backpack containing a 2G mobile network that can offer a coverage radius of up to 1,000 yards (1km), a six-hour battery and a small solar panel.

Vodafone Foundation's instant network mini kit has been used in South Sudan....

....and is small enough to fit in a backpack

It says aid workers or locals can have it up and running within 10 minutes.

"We realised that mobile telecoms tech can play a crucial role in disaster situations to reconnect people with their families," Oisin Walton, Vodafone Foundation's instant network programme manager, tells the BBC.

"It's also important for aid agencies trying to co-ordinate their efforts."

Earlier this year, the instant network mini kit was deployed in the Kathmandu valley, Nepal, to help restore communications following the devastating earthquake there. And larger versions of its instant network kits have been used in South Sudan and the Philippines.

The smartphone has certainly given people more mobile functionality but at the expense of battery life, so providing energy stations where displaced people can recharge their phones is also becoming increasingly important, Mr Walton argues.

...and a larger version was used in the Philippines following a particularly destructive typhoon

"The old Nokia phones would last for days, but smartphones use more power and don't last as long," he says.

The Foundation has developed charging blocks that can be screwed on to makeshift tables. They feature 20 USB ports for phone cables, can be linked in groups of three, and are recharged using generators or solar panels.

Crisis apps

Once you've established a viable local communications network, dissemination of crucial information is key for refugees, disaster victims and aid agencies alike.

But there's often a lot of confusion in crisis situations and duplication of effort because information isn't shared properly, field workers say.

So a number of organisations, from Google to Medecins du Monde, are working on apps that can act as single information points, connecting doctors in developed countries with health workers in the field, for example, or NGOs with other aid agencies, so each can know what the other is providing.

The MedShr app helps healthcare workers in disaster zones to seek second opinions online

And all this data from mobiles is proving valuable, too.

Swedish non-profit organisation Flowminder uses anonymised data from mobile operators to track the movements of populations - or their mobile phones - in disaster situations.

This can help governments and aid agencies understand people's behaviour and give them a better idea of where to channel resources.

"Based on their usual activity, we can see what areas phones belong in. Then, in a disaster scenario, we can see how many phones which belong in district A have moved to district B, for example," explains Flowminder chief executive, Linus Bengtsson.

Re-establishing communications in the rugged landscapes of Nepal requires portable solutions

There is no other reliable way of gauging where people are located or moving to, he says. And using historical data can also help predict future movements - and the likely spread of a disease, he maintains.

This kind of analysis has been used during the recent ebola crisis in west Africa and after the Haiti earthquake in 2010.

"Assuming mobiles are being used by infected people, we can predict where people, and the disease, will go," says Mr Bengtsson. "There could be the potential to stem the spread of infectious diseases in the early stages."

'Improving resilience'

Greater co-operation between mobile operators is also key to improving communications in crisis situations, believes the GSM Association (GSMA), the global trade association for the mobile industry.

"Since 2012, the GSMA has been working with our mobile operator members on improving resilience and capacity to respond to humanitarian crises, recognising the critical role that mobile communication plays for those affected by these crises," says Kyla Reid, head of disaster response at the GSMA's mobile for development unit.

Mobile phone data was used to predict disease outbreaks after the 2010 Haiti earthquake

"What is most important is that efforts are coordinated and the partnerships necessary to deliver them are structured ahead of time, so that when disaster strikes, the potential of mobile technology can be maximised," she says.

This year the GSMA launched the Humanitarian Connectivity Charter, which unites mobile operators around shared principles of preparedness, co-ordination and co-operation.

While technology alone cannot prevent the suffering that inevitably follows natural and man-made disasters, its better use can at least improve the response of governments, aid agencies and NGOs.

And give some autonomy back to people who've been dispossessed of almost everything else.