Programming in the early days of the computer age

- Published

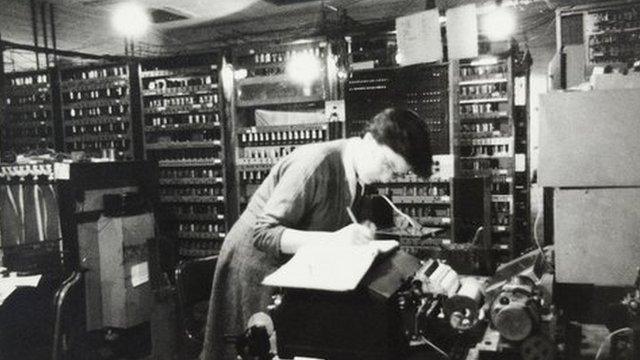

Joyce Wheeler was one of a select group of scientists who used Edsac in their research

Everyone remembers the first computer they ever used. And Joyce Wheeler is no exception. But in her case the situation was a bit different. The first computer she used was one of the first computers anyone used.

The machine was Edsac - the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator - that ran for the first time in 1949 and was built to serve scientists at the University of Cambridge.

Joyce Wheeler was one of those scientists who, at the time, was working on her PhD under the supervision of renowned astronomer Fred Hoyle.

"My work was about the reactions inside stars," she said. "I was particularly interested in how long main sequence stars stay on their main sequence.

"I wanted to know how long a star took to fade out," she explained.

The inner workings of the nuclear furnace that keep stars shining is an understandably knotty problem to solve. And, she said, the maths describing that energetic process were formidable.

"For stars, there's a rather nasty set of differential equations that describe their behaviour and composition," she added.

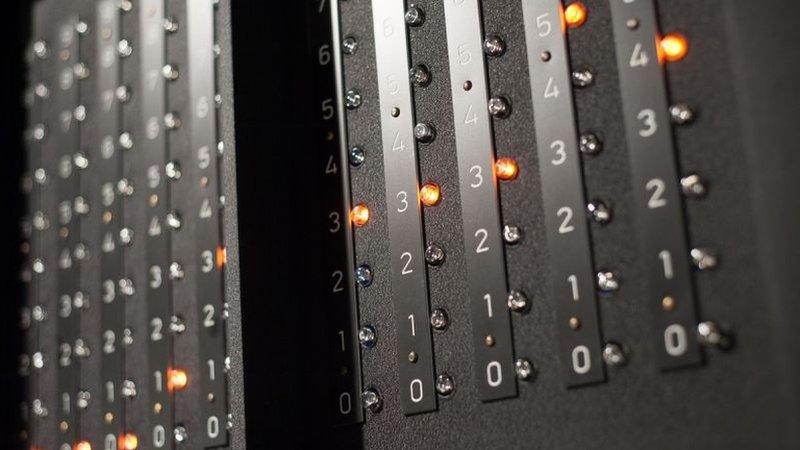

Edsac helped Dr Wheeler investigate what processes keep stars burning

Completing those calculations manually was futile.

"It was not possible to be really accurate doing it by hand," she said. "The errors just build up too much."

Enter Edsac - a machine created by Prof Maurice Wilkes to do exactly the kind of calculations Ms Wheeler (nee Blackler) needed done to complete her advanced degree.

Thinking time

First though, she had to learn to write the programs that would carry out the calculations.

Dr Wheeler started her PhD work at Cambridge in 1954 knowing about Edsac thanks to an earlier visit during which the machine had been shown off to her and others.

Keen to get on with her research she sat down with the slim booklet that described how to program it and, by working through the exercises in that pioneering programming manual, learned to code.

Research students like Joyce Wheeler had to use Edsac at night

The little book was called WWG after its three authors Maurice Wilkes, David Wheeler and Stanley Gill.

It was through learning programming that Ms Blackler got talking to David Wheeler because one of her programs helped to ensure Edsac was working well. They got to know each other, fell in love and married in 1957.

Now, more than 62 years on she is very matter of fact about that time - even though programmers, and especially women programmers, were rare.

Perhaps because of that novel situation, a new discipline and a pioneering machine, the atmosphere at Cambridge in the computer lab was not overwhelmingly masculine.

"You could be regarded as a bit of an object, and occasionally it was a bit uncomfortable," she said, "But it was not quite a boys' brigade then in the way that it became later on."

It was an exciting time, she said, because of what the machine could do for her and her work. She took to programming quickly, she said, her strength with maths helping her quickly master the syntax into which she had to translate those "nasty equations".

"But it was like maths," she said, "it was one of those things that you knew you should not do for too long.

The foundations of programming were laid down by Edsac's creators

"I found I could not work at a certain programming job for more than a certain number of hours per day," she said. "After that you would not make much progress."

Often, she said, the solution to a programming problem she had been worrying away at would strike while she was engaged in something more mundane, like doing the washing or eating lunch.

"Sometimes it's better to leave something alone, to pause, and that's very true of programming."

Night work

With the programming done, she could let Edsac do the number crunching. As a research student she had to run her programs during the night. In her case that was Friday.

"That was good because there were no lectures the next day that you had to go to," she said.

As an operator she was allowed to run Edsac alone, provided she signed in and kept a record of what she did.

"Quite often it would break down during the night, but just occasionally you were lucky enough to keep it running all night," she said. "If it did crash, there was little that operators were allowed to do to try to fix it.

"They didn't even let any of the cleaners get near it," she said.

Dr Wheeler had been shown one procedure that recalibrated Edsac's two kilobyte memory but if that did not help, then her work would stop for the night.

Despite the regular crashes, Ms Wheeler made steady progress on finding out how long different stars would last before they collapsed.

A copy of Edsac is being built at the National Museum of Computing

"I got some estimates of a star's age, how long it was going to last," she said. "One of the nice things was that with programming you could repeat it. Iterate. You could not do that with a hand calculation.

"We could add in sample numbers on programs and it could easily check them," she added. "I could check my results on the machine very rapidly, which was very useful."

Rapidly in the 1950s meant about 30 minutes for the machine to complete one run of a program. Then the results were printed out for researchers to pore over to see what results they had got. Then it was a case of re-programming and perhaps waiting a few days to have a chance to run a slightly modified program on Edsac.

Despite the delays, it was clear to Dr Wheeler that they were pioneers.

"We were doing work that could not done in any other way," she said. And even though Edsac was crude and painfully slow by modern standards, she saw that a revolution had begun.

"It was clear that one day, when the machines got bigger and faster, a lot of problems would start to be solved."

- Published2 April 2016

- Published7 December 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published18 November 2016