Tech Tent: France's tech ambitions

- Published

Stream or download, external the latest Tech Tent podcast

Listen to previous episodes on the BBC website

Listen live every Friday at 15:00 GMT on the BBC World Service

Just as Tech Tent was winding up last Friday, a message flashed on my screen about computer problems at NHS hospitals.

It rapidly became clear that one of the most damaging cyber-crimes we've seen was under way - and on this week's programme we look at what's emerged about the possible identity of the people behind the Wannacry ransomware.

But most of the programme comes from Paris, where we try to discover whether French technology is about to enjoy a renaissance under a youthful new president.

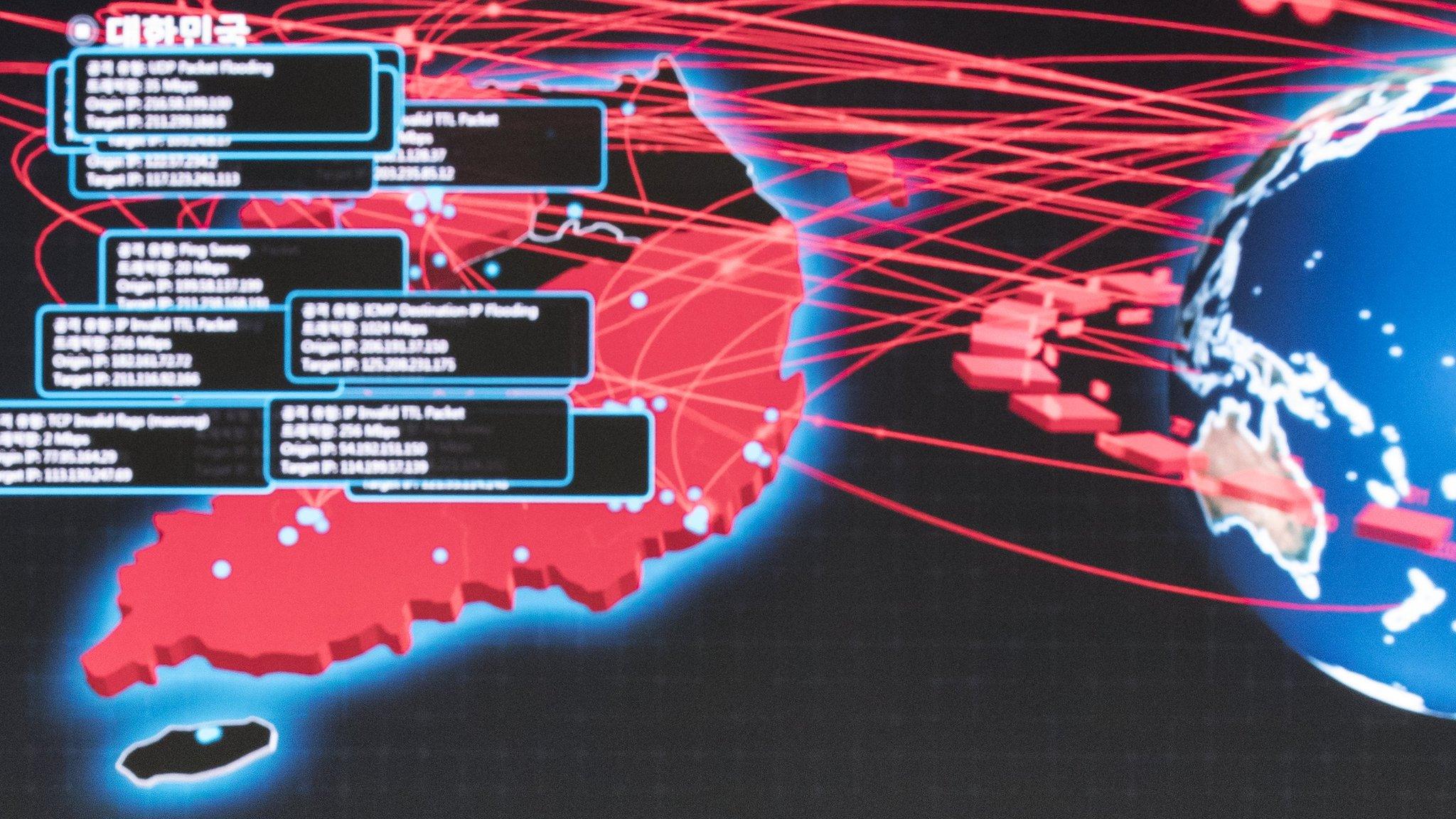

Tracking the ransom cash

There are a few theories but no firm leads about who was behind the Wannacry ransomware that infected hundreds of thousands of computers worldwide.

But the intriguing thing about this hugely damaging crime is that the perpetrators could end up with a meagre return. They demanded that victims wanting their frozen files unlocked pay the ransom into just three Bitcoin wallets - and that suggests that they may not be the most sophisticated of criminals.

Tom Robinson of Elliptic, a firm which tracks Bitcoin transactions, tells us that in many cases ransomware gangs create a separate Bitcoin address for each of their victims.

He says around $90,000 (£70,000) has arrived in the Bitcoin wallets so far, but moving the money out might look just too risky for the criminals.

The thieves behind WannaCry may never be able to cash in

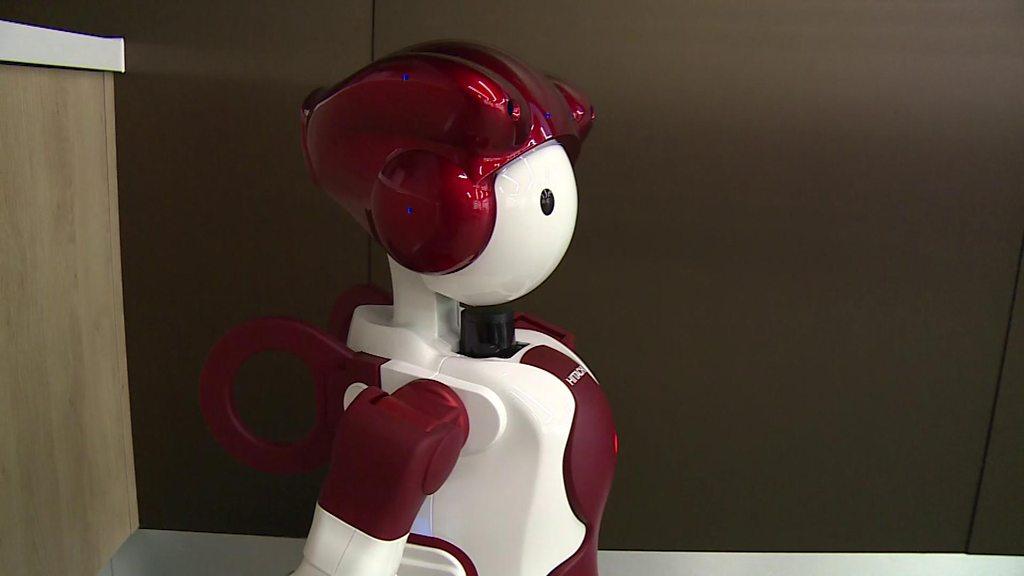

France's robot future

France is a country with a great tradition in engineering and design, the home of world beating firms such as Airbus and Renault. But when it comes to nurturing tech start-ups it has an image problem, being seen as a country with rigid labour laws, lots of red tape and an aversion to risk.

But one area where it excels is robotics, and at the annual Innorobo exhibition in Paris, we find a spirit of optimism about the future for this industry.

After a career in the aerospace industry, Norbert Ducrot has started a robotics firm with a big ambition - to solve the problem of caring for elderly people.

His Ubo robot is designed to keep an eye on its owner, sending health data collected from a smartwatch to doctors or relatives. It will be built in China, although the software and the design are made in France, and he aims to sell it for around the price of a high-end smartphone.

He says robotics is a vital industry for France. "The last 20 years was a revolution for the smartphone. The next 20 years will be a smartphone on wheels which is a robot."

Ubo will help to keep an eye on elderly relatives

Away from the show, in airy offices in the north of Paris packed with engineers, we find another innovative robotics firm. Keecker was started by Pierre Lebeau, who worked for Google both in France and in Silicon Valley.

His idea was to build a home media centre that you can summon to any room to project videos onto the wall, play music, or even allow a video call to friends. After four years of work, the product is due to go on sale in the autumn in France, the UK and the US.

It's an idea that seems more likely to have come out of Silicon Valley than France and he says his experience at Google taught him to think big.

But Pierre tells us to abandon our preconceived notions about his country: "Things have changed a lot in the past few years. We have a special status as a technology company, we pay a lot less taxes on employees and we have a great tax rebate. People's minds need to be changed - Paris is one of the leading capitals in Europe for start-ups."

And over at the former offices of newspaper Le Figaro, now the home to the leading venture capital firm Partech Ventures and some of the start-ups it backs, we found a similar mood.

"We French are not very good at promoting and marketing ourselves," admitted Marie-Hortense Varin but she reeled off a list of successful tech firms born in the past few years, including BlaBlaCar and adtech business Criteo.

The Keecker robot is a home helper and media centre

And as for the idea that the French are risk-averse: "Electing a president who's 39 years old and has never held an elected mandate - if that's not risk-taking I don't know what is," she says.

Just a few years ago, the digital minister Emmanuel Macron was an obscure figure, but as the man who championed small tech businesses he was the toast of the start-up community. Now he is president and Marie-Hortense cites his victory as evidence that things are changing.

But while across the tech community there is a lot of hope invested in the new president, there is also a sense of realism about what can be achieved. Others have tried before to water down the labour laws and the unions have brought thousands onto the streets to oppose them.

Ms Varin hopes change will come "in our French way", with a humane attitude to healthcare and other protections. But she is one of a new generation determined that France should start making the most of its undoubted technology skills.

- Published15 May 2017

- Published5 May 2017

- Published5 May 2017

- Published2 May 2017