Would you hack your own body?

- Published

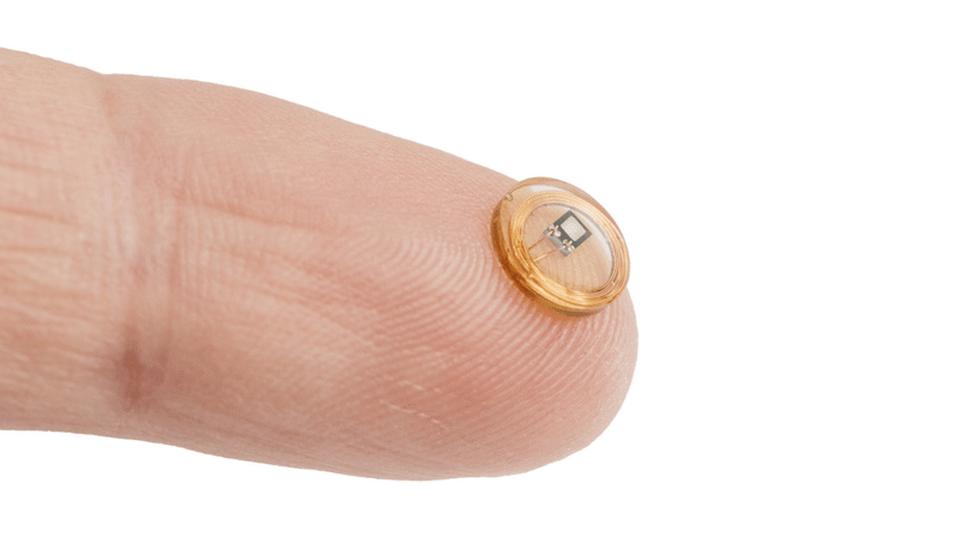

An estimated 10,000 people now have chips under their skin - but this one is just a mock-up!

At a trendy east London bar, a group of body hackers are putting forward their reasons for human augmentation to a packed audience of mainly under-35s, many of whom are sporting piercings and tattoos.

Putting a chip under your skin is not so very different from getting a piercing or tattoo, argued one of the panellists - except there was often less blood.

For some, transhumanism - the theory that the human race can evolve beyond its physical and mental limitations with the help of technology - is a crucial part of the advancement of society.

Lepht Anonym has plenty of implants

Bio-hacker Lepht Anonym has nine implants and strongly believes what she does will benefit humankind as well as her own curiosity.

But she admits it can be painful.

"The magnets in my fingers really, really hurt. They hurt so much that your vision goes white for a bit. Really, really painful."

The magnets allow her to sense electromagnetic radiation so she can tell if a device is on or off, whether a microwave is running and identify where power lines are. All of which, she admits, is "not hugely useful".

She also has a chip under her skin that lets her interact with her phone and unlock doors.

She hopes that the "primitive results" she has achieved can be used by other, more skilled people, to build something better.

"The bio-hacking community is a co-operative. It is about improving the quality of life for people but in a practical way."

Hygiene issues

Not everyone is a fan of the trend. Andreas Sjostrom, who leads CapGemini's global mobility practice, had an implant in 2015 which allowed him to download his customer number from airline tickets and get through security gates with a swipe of his hand.

It got him noticed by security staff at the airport and worked but he has since become more cynical about the technology.

"In order for this to be widely used or adopted it has to improve on the current situation," he said.

"The hardware that reads such chips is designed for a flat surface such as you'd find in a card," he explained, adding that chips in hands are often not recognised by the readers.

"And, if everyone is pressing their hands on the reader, that is less hygienic."

It is estimated that more than 10,000 people around the world have chip implants in their bodies, making it far from mainstream but clearly a growing trend.

The current range of implants includes magnets that are installed into fingertips, radio frequency identification chips (RFiD) implanted in hands, and even LED lights that can shine beneath the skin.

The chips are tiny

Chips used for opening doors carry a unique serial number the can be read by a device attached to whatever you want to open and one chip can carry multiple numbers meaning you do not need a separate chip for everything you want to access.

Amal Graafstra provides such implants via his firm Dangerous Things and thinks there are three good reasons to have an implant.

"We all carry with us keys, wallet and phone. These are major burdens, they are so important for modern life but everyone hates carrying them.

"With a simple implant that uses less energy and carries less risk than an ear-piercing, you can replace them."

He is able to access not only his house but his car via the implant under his skin, although he admits that getting the device to work with his car required "a bit of hacking".

But he envisions a future where chips can do far more - and that, he predicts, will attract more people to the community of bio-hacking.

"If someone could use an implant to get on the train, buy coffee, secure their computer, secure their data, get into their house, drive a car - all of these possible applications will compel a lot more adoption."

Matt Eagles' implant has left a scar on his chest and two small bumps on his head

For Matt Eagles, the implant he has in his brain is not a luxury so much as a necessity to cope with the Parkinson's disease he has had since he was a child.

He has two 15cm electrodes that run deep into his brain and create two bumps on his head which he affectionately refers to as "baby giraffe horns".

The implants are attached to a pulse generator in his chest, which disrupts the electrical signals to his brain and allows him to walk.

"They have given me back my dignity. When you struggle to turn over in bed at night or can't get out of bed to go to the bathroom, to be suddenly able to do so is a huge plus."

It has also given him back confidence to pursue his love of photography - he was an accredited football photographer at the 2012 Olympics - and, perhaps most importantly, he has got married.

Some bio-hackers have gone one stage further - triggering a change in their own DNA

Many regard medicine as being the real mainstream application for bio-hacking, from cochlear implants which improve hearing loss to smart pills that can be ingested and access, analyse and manipulate bodily functions.

Some bio-hackers are ready to go one step further. In October 2017, Josiah Zayner, who has a doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biophysics from the University of Chicago, injected his arm with DNA from a gene-editing tool called Crispr.

It is a stunt that he has since said he regrets but his attempt to edit his own genes - in this case to trigger a genetic change in his cells to increase muscle mass - made headlines at the time, largely around the ethics of such experimentation.

"There is a continuum between therapy and enhancement and it is difficult to draw the line between where medicine ends and enhancement begins," said Prof John Harris, an ethicist from the University of Manchester.

"As for gene editing the tools are available and relatively cheap and easy to use, but people would be extremely ill-advised to try it."

There has also been objections on religious grounds from some, with Mr Sjostrom receiving negative feedback from a group in the Christian community.

"They see implantable technology and assume the end of times are here and that it is the mark of the beast. It is important to know how to deal with this technology from a theological point of view."

- Published21 November 2017

- Published8 February 2018