GoFundMe: Hope, but no solution, for the needy

- Published

Kelsey's family is raising money to cover treatment costs for a rare condition

Kelsey Colker is less than a year old but she's already spent more time in hospital than most of us will in our lifetime.

She has a rare condition known as "vanishing gut syndrome", causing her to lose most of her intestines.

Treatment is painful, long and - of course - expensive.

"I was not prepared for this situation and the astronomical medical bills I've faced," Kelsey's mother, Patricia, told me.

Like millions before her, Patricia has turned to GoFundMe, a site that provides a crowd-funding platform and tools to help worthy causes receive attention across social media.

"The heartfelt donations Kelsey receives through her GoFundMe page are a godsend in helping to pay medical bills, and giving her a fighting chance," Patricia said.

The last hope

In today's world, for a sick child, going viral can mean the difference between life or death. Or, it means an injured firefighter, has the chance of a full recovery. It means hundreds of lawyers for women who were victims of sexual harassment, or food for federal workers staring down financial ruin after weeks of not being paid.

Indeed, California-based GoFundMe has become the last hope for many Americans, in a country where social safety nets can be tragically hard to come by. The site has a growing number of international users too.

Since 2010, more than 50 million people have donated more than $5bn (£3.9bn). At first, the site took a 5% cut of donations but now it takes no fees in most markets, asking instead for givers to essentially tip the website instead.

For some, the success of GoFundMe stands as proof of humanity's innate desire to help each other. For others, the site's continued existence is a monument to inequality.

"The risk is that we are lulled into thinking that generosity is a substitute for justice," said Anand Giridharadas, author of Winner Takes All, a book that examines the forces behind income inequality.

A broken system

"It's biblical in nature," Rob Solomon, GoFundMe's chief executive, told me.

"I mean, in the old days, when someone needed to build a barn, it wasn't the family that was building the barn that built it, the whole community came together. This is something that is deeply seated in human nature, this notion of coming together to help people."

Fundraisers such as Kelsey's are common on the GoFundMe platform, where medical issues make up the bulk of campaigns

Our interview took place, not in a barn, but in a conference room named Saving Eliza, after a little girl whose father raised enough money to fund a clinical trial to help fight Sanfilippo syndrome, a rare genetic disorder.

Other rooms in the building include Help Norma, named after an 89-year-old who was able to afford stay-at-home care after her 31-year-old neighbour raised over $50,000.

Medical needs are the most frequent type of fundraisers on the platform, not just covering medical bills, but other areas where money can fall short when a family member is taken ill.

Many of the fundraisers existed because of a "broken" healthcare system in the US, Mr Solomon said.

"I wish GoFundMe didn't need to be around to solve problems that shouldn't exist.

"Everyone should have access to health care. I would love for there never to be another medical campaign on GoFundMe. But that's not the reality we live in."

Funding the wall

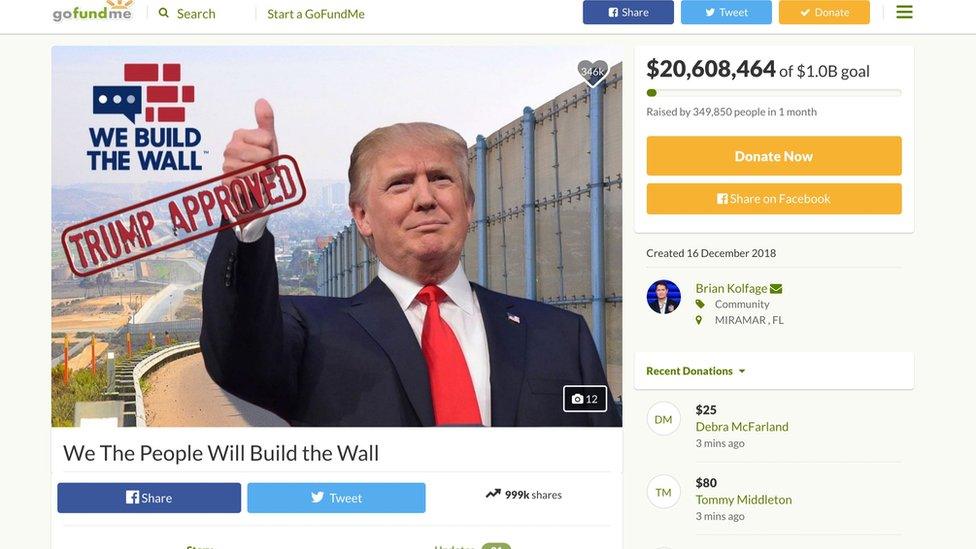

Increasingly, the question of what constitutes a "good cause" is becoming highly politicised. We The People Will Build The Wall is a GoFundMe campaign launched in December with the goal of raising money for the President Donald Trump's proposed border wall between the US and Mexico.

"The feasibility was something that we didn't have great certainty on," Mr Solomon said, in response to my question of whether it was obvious the campaign would never succeed in funding a border wall.

"There is precedent where private funds have gone to the government to fund certain causes. [But] in working on this, we realised that that wasn't going to be the case and we let the campaign organiser know that he would have to find a different use case."

A campaign to raise money to hand over the Trump administration for a border wall was deemed not feasible by GoFundMe

That use case ended up being a separate company that, organisers said, would be capable of building the wall itself. Those who had donated up until that point were given their money back, unless they opted-in to funding the new company instead.

GoFundMe said it would not intervene in campaigns on political grounds unless a fundraiser went against its policies.

"The money isn't released to a fundraiser or a beneficiary until we can confirm where the money is going," Mr Solomon said.

Increasingly, though, machinations in the political world are having a direct impact in the work that GoFundMe is doing.

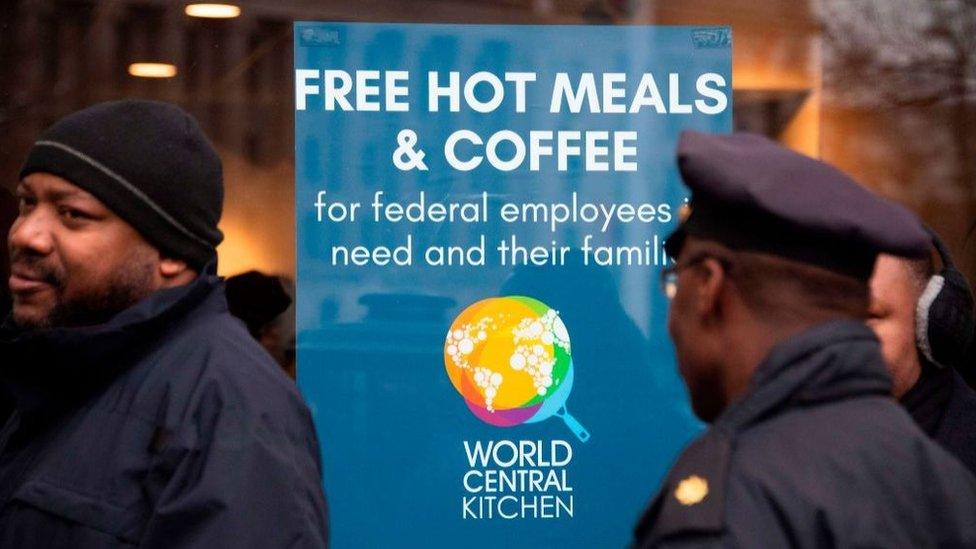

During the recent government shutdown, when about 800,000 workers missed a pay cheque, GoFundMe raised just under half a million dollars to help those affected, in addition to the individual campaigns started by friends and family of furloughed workers.

"It's a sign of dysfunction," Mr Solomon said. "The government not doing what it's supposed to do."

Fighting scams

The rapid growth of GoFundMe has presented another major challenge for its 300 employees: verifying the authenticity of those asking for money. Sometimes fake campaigns slip through the net, such as a recent fund for a shooting victim that never existed.

One of the most high-profile fundraisers on GoFundMe featured three people who prosecutors allege concocted a wild storyline about a homeless man giving a woman his "last $20".

The story quickly went viral, gained widespread media coverage, and soon more than $400,000 had been raised - donations that GoFundMe has since refunded.

GoFundMe set up a special programme to fund organisations helping workers affected by the US government shutdown

"Less than one 10th of 1% of all campaigns result in any kind of misuse or fraud," Mr Solomon said.

"We take it very seriously. We have a host of technologies, we have many different processes and lots of people that we deploy, to keep misuse off the platform."

No substitute

While it's the big viral campaigns that get the most attention, Mr Solomon is keen to point out that the average GoFundMe campaign raises in the region of $1,500.

Many of these smaller campaigns can be found in the education section of the site, where school teachers are asking for help buying things such as computers, books and even tables - essential items in a classroom that most people might reasonably expect to be covered by taxes, not donations.

"Income inequality is a big driver of why we exist," Mr Solomon said.

Mr Giridharadas said "GoFundMe culture" was papering over what should be "properly public priorities".

"People are moved by stories of teachers whose classrooms are bare and patients shut out of proper medical care," he said.

"[But] many GoFundMe campaigns are testimony to a cruel, winners-take-all economy, the only remedy for which is vigorous reform of law and policy - and the winners taking less."

- Published15 August 2017

- Published16 November 2018