DeepMind's AI agent MuZero could turbocharge YouTube

- Published

MuZero was tested against Atari video games, chess and other classic board games

DeepMind's latest AI program can attain "superhuman performance" in tasks without needing to be given the rules.

Like the research hub's earlier artificial intelligence agents, MuZero achieved mastery in dozens of old Atari video games, chess, and the Asian board games of Go and Shogi.

But unlike its predecessors, it had to work out their rules for itself.

It is already being put to practical use to find a new way to encode videos, which could slash YouTube's costs.

"The real world is messy and complicated, and no-one gives us a rulebook for how it works," DeepMind's principal research scientist David Silver told the BBC.

"Yet humans are able formulate plans and strategies about what to do next.

"For the first time, we actually have a system which is able to build its own understanding of how the world works, and use that understanding to do this kind of sophisticated look-ahead planning that you've previously seen for games like chess.

"[It] can start from nothing, and just through trial and error both discover the rules of the world and use those rules to achieve kind of superhuman performance."

Dr Silver says MuZero gets us closer to having AI agents that can cope with the messiness of the real world

Wendy Hall, professor of computer science at the University of Southampton and a member of the government's AI council, said the work marked a "significant step forward", but raised concerns.

"The results of DeepMind's work are quite astounding and I marvel at what they are going to be able to achieve in the future given the resources they have available to them," she said.

"My worry is that whilst constantly striving to improve the performance of their algorithms and apply the results for the benefit of society, the teams at DeepMind are not putting as much effort into thinking through potential unintended consequences of their work.

"I doubt the inventors of the jet engine were thinking about global pollution when they were working on their inventions. We must get that balance right in the development of AI technology."

Video compression

London-based DeepMind first published details of MuZero in 2019, external, but waited until the publication of a paper in the journal Nature, external to discuss it.

It represents the firm's latest success in deep reinforcement learning - a technique that use many-layered neural networks to let machines teach themselves new skills via a process of trial and error, receiving "rewards" for success rather than being told what to do.

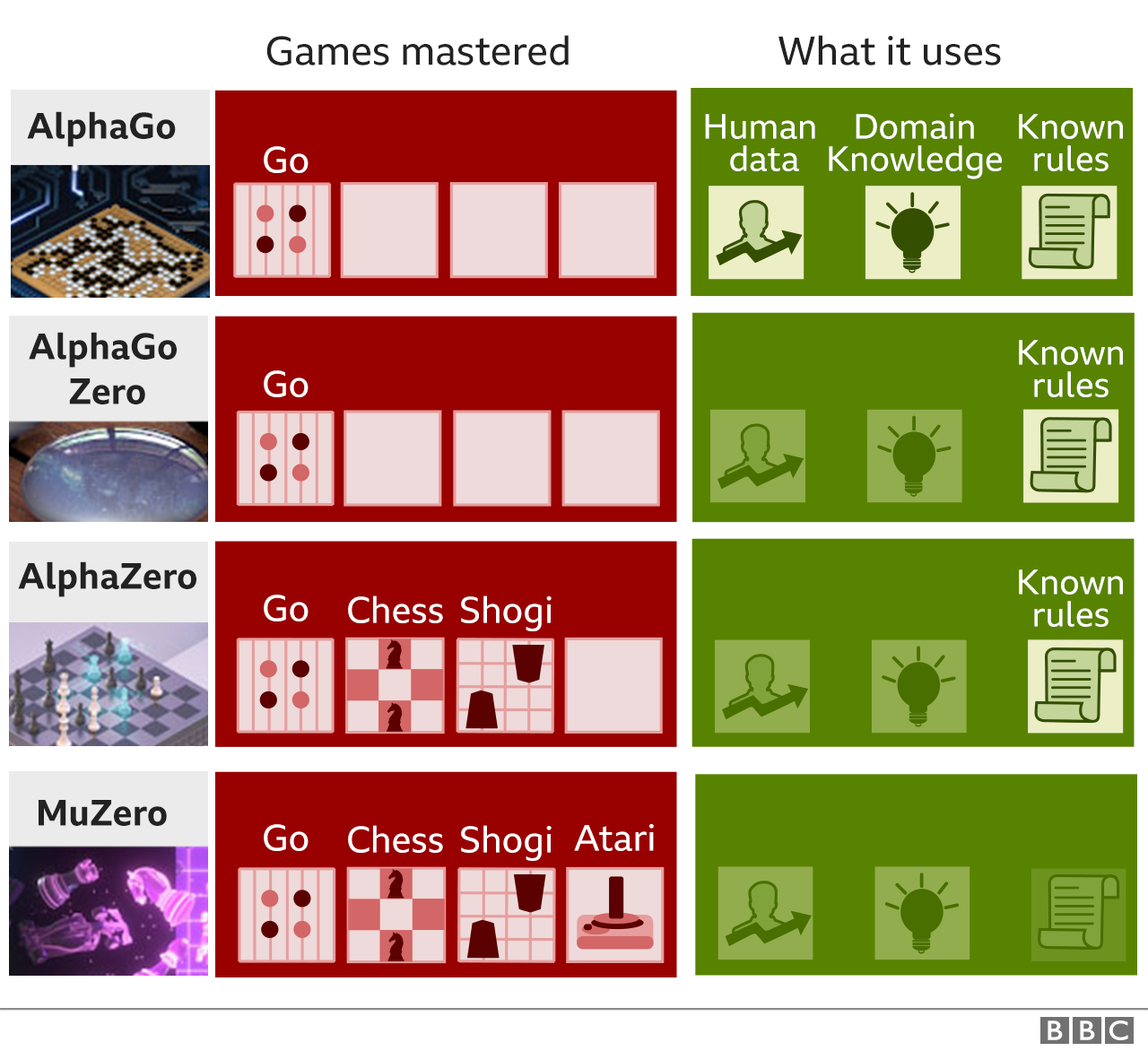

MuZero follows in the footsteps of:

a program referred to as DQN, which achieved human-beating proficiency in Atari video games using only pixels and game scores as input

AlphaGo, the program which beat master Go player Lee-Sedol 4-1 in a groundbreaking competition in 2016, after being trained on past games

AlphaGo Zero, which surpassed AlphaGo in performance the following year after training itself from scratch having only been provided with the basic rules of the game

AlphaZero, which in 2017 generalised AlphaGo Zero so that it could be applied to others games, including chess and Shogi

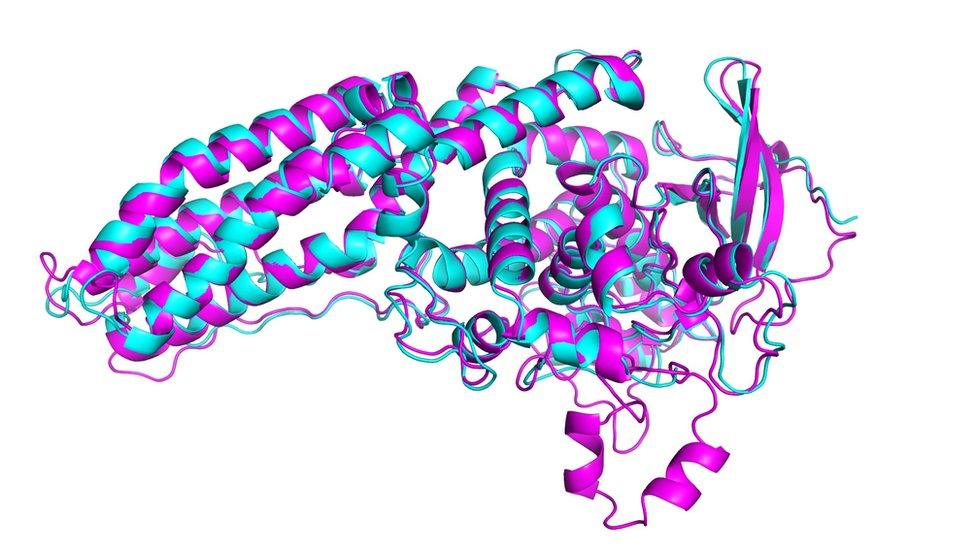

Most recently, DeepMind - which is owned by the same parent as Google's - made a breakthrough in protein folding by adapting these techniques, which could pave the way to new drugs to fight disease.

MuZero could soon be put to practical use too.

Dr Silver said DeepMind was already using it to try to invent a new kind of video compression.

"If you look at data traffic on the internet, the majority of it is video, so if you can compress video more effectively you can make massive savings," he explained.

"And initial experiments with MuZero show you can actually make quite significant gains, which we're quite excited about."

He declined to be drawn on when or how Google might put this to use beyond saying more details would be released in the new year.

However, as Google owns the world's biggest video-sharing platform - YouTube - it has the potential to be a big money-saver.

Squeezing data

DeepMind is not the first to try and create an agent that both models the dynamics of the environment it is placed in and carries out tree searches - deciding how to proceed by looking several steps ahead to determine the best outcome.

However, previous attempts have struggled to deal with the complexity of "visually rich" challenges, such as those posed by old video games like Ms Pac-Man.

MuZero was provided with the pixels of the Ms Pac-Man game but not its rules

The firm believes it has been successful because MuZero only tries to model aspects of the environment that are important to its decision-making process, rather taking a wider approach.

"Knowing an umbrella will keep you dry is more useful to know than modelling the pattern of raindrops in the air," it explains in a blog.

The Nature paper reports that MuZero proved to be slightly better than AlphaZero at playing Go, despite doing less tree-search computation per move.

And it said it also outperformed R2D2 - the leading Atari-playing algorithm that does not model the world - at 42 of the 57 games tested on the old console. Moreover, it did so after completing just half the amount of training steps.

Both achievements point to the fact that MuZero is effectively able to squeeze out more insight from less data than had been possible before, explained Dr Silver.

"Imagine you've got a robot and it's wandering about in the real world and it's expensive to run," he said.

"So you want it to learn as much as possible from the small number of experiences it has. MuZero is able to do that."

He added that other potential uses included next-generation virtual assistants, personalised medicine and search-and-rescue technologies.

- Published2 December 2020

- Published30 November 2020

- Published30 October 2019