Government lays out plans to protect users online

- Published

The Online Safety Bill is designed to protect children and adults

Social media firms will have to remove harmful content quickly or potentially face multi-billion-pound fines under new legislation.

The government's Online Safety Bill, announced in the Queen's Speech, comes with a promise of protecting debate.

It is "especially" geared at keeping children safe and says "democratically important" content should be preserved.

But campaigners say the plans will lead to censorship, while others warn fines do not go far enough.

What is covered in the bill?

The draft legislation, previously known as the Online Harms Bill, has been two years in the making.

It covers a huge range of content to which children might fall victim - including grooming, revenge porn, hate speech, images of child abuse and posts relating to suicide and eating disorders.

But it goes much further, taking in terrorism, disinformation, racist abuse and pornography, too.

Late additions to the bill include provisions to tackle online scams, such as romance fraud and fake investment opportunities.

It will not include fraud via advertising, emails or cloned websites.

Digital Secretary Oliver Dowden said the "ground-breaking laws" would usher in "a new age of accountability for tech".

And Home Secretary Priti Patel added the scam provisions would help fight "ruthless criminals who defraud millions of people".

New details published about the government's Online Safety Bill again emphasise its commitments to enforce social media sites to better protect users from online harm. That includes child sexual exploitation, racist abuse, terrorism - and harmful disinformation on social media.

I've spent the past year investigating the very real-world harm myths and conspiracy theories shared online - about the pandemic, vaccines, and elections - can cause offline.

Under the proposals, social media sites will be required to act on harmful content like this - even when legal. Otherwise, they'll find themselves at risk of fines or even criminal action from regulator Ofcom.

The line between free speech and harm posed by misleading posts online has been a tricky one to tread for tech companies - and with a nod to the on-going debate, the bill highlights the importance of freedom of expression on social media.

While more concrete plans will be welcomed by critics of the social media giants, the government has come under fire for repeated delays to this legislation.

But those who I've interviewed - who have already been impacted by online conspiracies - would argue this comes too late to protect them and their loved ones.

What about free speech?

The government has added a new duty of care for social-media sites to protect content defined as "democratically important". This includes content promoting or opposing government policy or a political party ahead of a vote, election or referendum.

Context will also need to be taken into account when moderating political content.

While content on news publishers' websites is not part of the legislation, articles shared on social media are.

Social-media firms should offer a fast-track appeals process if journalistic content is removed, both from professional and "citizen" journalists, it says.

But campaigners remain unhappy.

Ruth Smeeth, the chief executive of the Index on Censorship who has personal experience of online abuse, described the bill as a "censor's charter... outsourced to Silicon Valley".

The former Labour MP added that "targeting the platforms rather than the perpetrators of hate seems a strange proposed solution".

Jim Killock, executive director of the Open Rights Group, warned the idea that speech was "inherently harmful" and needed to be controlled by private companies was "very dangerous".

The government said companies would need to "put in place safeguards for freedom of expression" and have effective routes for users to appeal.

Users will also be able to appeal directly to Ofcom.

How will it be enforced?

Ofcom will issue codes of practice outlining the systems and processes that companies need to adopt in order to be compliant.

The government has already published codes on terrorism and child sexual exploitation because of their serious nature.

The largest and most popular social-media sites - described as category-one services - will need to state explicitly in their terms and conditions how they will address so-called legal harms.

Ofcom will be able to issue fines of up to £18m or 10% of global turnover, whichever is higher, if firms fail to comply with the new rules.

It will also have the power to block access to sites in the UK, the government said.

Does it go far enough?

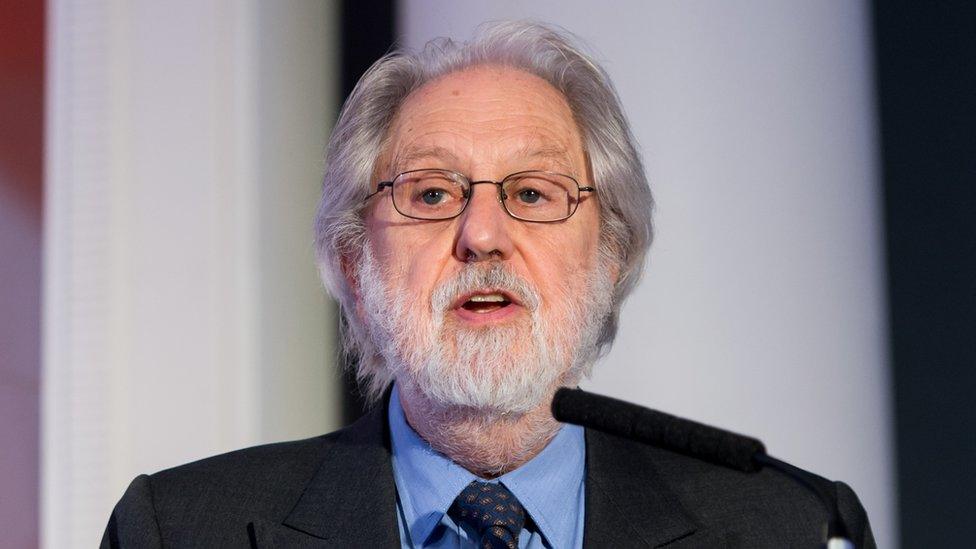

The death of Molly Russell prompted calls for tougher rules to be imposed on online services used by teenagers

Some campaigners do not think so.

Tech entrepreneur Belinda Parmar said: "The ambition is great. The regulator is going to have teeth, but no codes of practice for non-legal harms have yet been published, and it is all very vague."

Others have said fines do not go far enough, including the NSPCC which has called for the senior managers of tech firms to be made criminally liable for harmful content.

Labour called the proposals "watered down and incomplete" and said the new rules would do "very little" to ensure children are safe online.

The government has reserved the powers for Ofcom to pursue criminal action "if tech companies fail to live up to their new responsibilities". A review will take place two years after the new regime is operational.

Ian Russell, father of Molly, who killed herself in 2017 after viewing thousands of posts about suicide and self-harm on social media, said he hoped the new law would "focus the minds of the tech platforms" to change their corporate culture and to reduce online harms.

What next?

There has been frustration that the legislation, first conceived by Theresa May's government back in April 2019, has taken a long time to come to fruition.

The bill will now be examined by MPs on the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee, whose chairman, Julian Knight, said it would be pressing for the legislation "to be given top priority".

Related topics

- Published29 June 2020

- Published15 December 2020