How terror bill will expand powers

- Published

- comments

Theresa May: "We are engaged in a struggle that will go on for many years"

Within living memory, the UK has experienced the Nazi Blitz and the IRA's bloody bombing campaign - yet on Monday Home Secretary Theresa May said the growing number of jihadists was perhaps now the greatest threat to the nation.

She said the country's security and intelligence agencies were engaged in a struggle on many fronts and in many forms - and she was personally overseeing moves day after day to deal with suspects linked to the self-styled Islamic State and other groups.

For a decade, British security and intelligence agencies have tried to counter violent attacks from individuals inspired by al-Qaeda's ideology.

Broadly speaking, they have been largely successful - although sometimes that success is down to some sheer good fortune.

Two murders last year - Fusilier Lee Rigby by jihadists in Woolwich and Mohammed Saleem by a far-right killer in Birmingham - are obvious reminders that extremists will find ways to strike.

Today, the threat from some IS followers to the UK is probably the greatest of the politically-inspired extremist dangers.

And that's why Theresa May says the "time is right" to give the spooks and the cops more tools. But what would they achieve? And do they really need them?

Much legislation

This is the seventh major piece of counter-terrorism legislation since 2000.

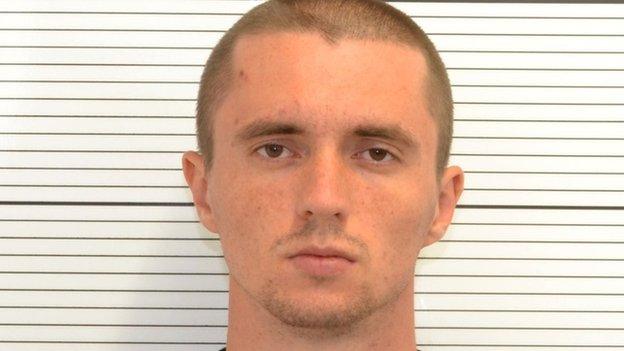

Pavlo Lapshyn was jailed for at least 40 years for murdering Mohammed Saleem

Critics, such as Liberty and Muslim campaign group Cage say this bill is illiberal, disproportionate and dangerous.

In contrast, the Home Secretary says that is is measured package which is consistent with the long-term security strategy that both her and the previous Labour administration have pursued.

The legislation doesn't create a long list of new offences - they're not needed. Instead, it aims to "disrupt" and counter the activity of suspects by other means.

Now, the obvious question is, surely the government wants suspected terrorists in court? That, of course, is true.

But ministers and security chiefs argue that very often the police can't gather criminal evidence because their suspicions are built on secret intelligence - for example information from an informant whose safety is at risk if their work is revealed.

So since 9/11 the UK has progressively developed a suite of counter-terrorism and security powers that allow ministers to use this partial intelligence picture, rather than hard crystal-clear evidence, to restrict or monitor suspected extremists.

The new legislation continues that trend and it will inevitably mean ministers will have more executive power over suspected extremists that will be largely exercised behind closed doors.

The controversial Temporary Exclusion Orders is the most obvious example. This measure will allow the Home Secretary to stop a suspect who is overseas from coming home for up to two years at a time, unless they comply with some form of investigation or monitoring.

Secret process

We haven't seen the detail yet, but the Home Secretary's decision-making on this will almost certainly occur in secret because case files will be based on MI5 assessments.

That is broadly the process that lies behind court-backed "T-Pim" monitoring arrangements and the separate but little-reported Treasury powers to freeze assets and bank accounts.

Such orders can be challenged in court - as can attempts to strip nationality or deport on national security grounds.

But critics say that if a suspect wants to return home after their passport has been cancelled, they will face an injustice of having to comply with the state's wishes before they have had a chance to put their own case.

Another of the measures may also prove to be equally problematic in Parliament and ultimately the courts.

The government wants to place a legal duty on public bodies to stop extremism.

This will compel universities, among others, to take steps to bar suspected extremist preachers.

If they don't, then ministers will be able to intervene and force the institution to act.

Here's the problem: Who defines who is an extremist speaker? How does one make that assessment? On what evidence and how could it be challenged?

Anyone can spot a violent jihadist or racist because they tend to overtly threaten the safety of the public. But what about someone who is just plain offensive? What if your interpretation of what they are saying bears no resemblance to theirs?

This may sound theoretical but it is so difficult for resolve that Conservative plans to create "extremism disruption orders" are currently a manifesto pledge and nothing more.

But there is something else far more important missing from the wish list.

Security chiefs are desperate to have full legal powers to access, intercept and analyse modern electronic communications data - the information about who is contacting who, rather than the separate issue of what is actually being said.

This is a row that goes back to 2008 - and it remains unresolved because of the allegation that is amounts to a "snoopers charter".

Even if Wednesday's legislation hurtles through Parliament with barely any debate, don't expect it to be long before a Home Secretary is back saying that more powers are needed to combat a complex and ever-changing threat.

- Published24 November 2014