Police play cat and mouse with online jihadists

- Published

A cat and mouse game is taking place every day on the internet. It is the online battle to deny space to extremist content.

On one side of the frontline are a team based in New Scotland Yard - the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police.

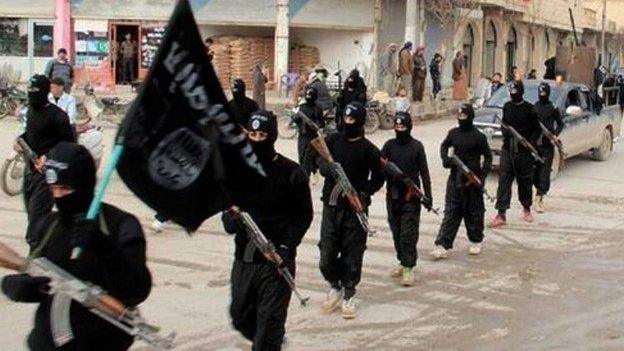

On the other are jihadists based in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere posting propaganda videos online - the most grisly of which show the beheading of hostages.

"We take stuff down, they put more stuff up," explains one of the Scotland Yard team who spoke to the BBC but asked to remain anonymous for his own security.

He is passionate about the importance of his job even though it has its challenges.

"It can be quite draining having to continuously see graphic and horrible images," he says.

"In our department we're huge fans of social media generally, but what we don't want to see is young people having access to material which could be extremely disturbing such as a beheading video and be for example, swapping it on online platforms between themselves at school."

Each member of the team is assigned a different jihadist media team so they can learn their behaviour - where and how they post their videos - and move as fast as possible to get them taken down.

"There are certain groups we chase from platform to platform and we know we've been effective because they will leave a message on a social media platform saying that they are moving somewhere else. We'll then target them at that one."

Three decades ago, Margaret Thatcher talked of the need to "find ways to starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity".

It was a time when those associated with violence in Northern Ireland were seeking airtime for their political statements and tensions were high between government and broadcasters.

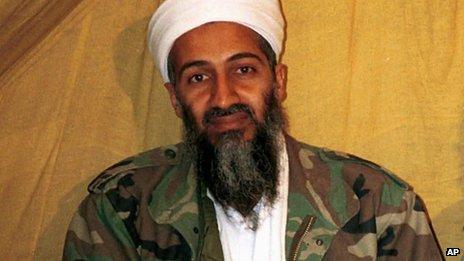

In the 1990s, Osama Bin Laden had to rely on more basic means of communication

Even in the nineties, Osama bin Laden still needed to invite US TV crews to come to him in Afghanistan in order to deliver his threats.

But a decade ago the dynamics between terrorism and the media began to change. Iraq was where that first became visible.

Increasingly, jihadists belonging to Al Qaeda in Iraq were filming their own attacks and then uploading them to the internet.

At first getting the material online was hard - it took technically-adept helpers to distribute it online. But in 2005, a new world of social media was just emerging.

Youtube, Twitter and other platforms would make direct communication easier.

The jihad was going online and this is where media wars would be played out in future.

Robert Hannigan became head of GCHQ in November 2014

This has meant that the tension between state and media over giving terrorists the oxygen of publicity has shifted from (domestic) TV Broadcasters to (largely American) social media companies.

Witness new GCHQ Director Robert Hannigan's broadside against them on his first day in the job.

He wrote in the Financial Times that they were "in denial" about the way they had "become the command-and-control networks of choice for terrorists and criminals".

Those technology companies say they are already working effectively to deal with extremist content on their sites.

One of the avenues for partnership is the team - known as the Counter Terrorism Internet Referral Unit - based at Scotland Yard.

The police officers get confirmation that the material they spot breaches UK law by encouraging and glorifying terrorism and then contact the social media companies.

Google receives around 1,000 reports a day of suspected inappropriate content

Google says that the UK team has a 96% accuracy rate - meaning that it only disagrees with one in 25 requests to take down content.

This compares to an overall average of 31% for reported content.

Google says it receives around a 1,000 reports a day of content that people believe should not be on the site which are reviewed individually to see if the material is in breach of the community guidelines.

Google says items which are found to be in breach are typically taken down in under an hour.

Could they do more? Google argues that it cannot review content before it is posted.

"We have 300 hours of video uploaded every minute so the idea of proactive review would be like asking the phone companies to review every phone call before it was made," argues Victoria Grand, a director of public policy for Google, which also owns Youtube.

The company also argues that automated detection is simply not possible.

It says that even its algorithms to try to spot pornography cannot be automated since searching for pictures with large amounts of flesh tones might also pick up innocent shots of babies.

There are also issues in recognising the difference between a news report which may carry a still or segment from a hostage video and the raw video itself. Google also says it does not want to remove everything which simply refers to a group like Islamic State since that would also remove journalistic material put out to counter its message.

Other companies have tightened up their procedures.

The website Ask.fm allows people to ask and answer questions anonymously. It is used heavily by young people.

That has included people offering information about jihad in Iraq and Syria.

Under new ownership, Ask.fm says it has learnt from the past by introducing things like reporting buttons.

Annie Mullins, who has taken over as lead safety advisor for the site, also points to the fact that people frequently use the site to have innocuous chats about other subjects before then moving to a different and more private messenger platform to actually try to recruit them.

So should the company be relying on requests from the police or the public rather than proactively looking for extremist content?

"If you look at Ask.fm, it has 28 million questions a day," says Ms Mullins, "so I think the impracticality is obvious and I think that's the same for other platforms," she argues.

"The police have to do their job and we do our job," she goes on, "which is to try and manage our community to the best standards that we've got using the best tools we've got."

While the UK has focused on removing content - trying to deny the oxygen to extremists - the US government has placed more emphasis on contesting that space.

Ambassador Alberto Fernandez is the US State Department's Coordinator for Strategic Counterterrorism. The Department runs campaigns on Twitter and social media forums to challenge extremists directly, with titles such as "Think Again, Turn Away".

These have been criticised in some quarters but he believes that engaging the jihadists' audience rather than ignoring them means they are exposed to alternative views.

But, like the Metropolitan Police team, his staff are few in number, with only around 20 engaging on a daily basis with jihadists in Iraq and Syria.

"We see ourselves as a rag-tag guerrilla organisation waging a hit and run campaign against the adversary," Mr Fernandez told the BBC. "We're definitely the David against the ISIS Goliath, which is perhaps somewhat ironic."

That means in this game of cat and mouse, the jihadists in Syria and Iraq engaged in putting out their message may well outnumber those in London and Washington who are trying either to take it down or to counter it.

And as the tide of jihadist propaganda continues to swell, the tensions over how to deal with it between government and media are likely to grow too.

Listen to Gordon Corera's documentary, Terror and the Oxygen of Publicity, at 8pm, Tuesday 23rd December, on BBC Radio 4.

- Published4 November 2014

- Published14 November 2014

- Published25 June 2014

- Published4 November 2014